Philips: Seeing business in a new light

Philips is implementing sweeping changes in its health care and lighting businesses in India to grow and retain its hard-won market leadership

Patients visiting the radiology department of the Sawai Man Singh Hospital in Jaipur, Rajasthan, dreaded the long queues that awaited them at the MRI and CT scan sections. The outdated equipment rendered the process slow and only 50-odd patients could be serviced in a day. The backlog of cases thus extended to many weeks. This was in 2012 and several patients, despite many of them coming from poor economic backgrounds, chose to get their tests done at more expensive private diagnostic centres rather than wait for hours.

Not anymore. The radiology department of the government hospital now boasts two high-end, 3 Tesla MRI scanners and two 128-slice CT scanners costing a total of Rs 30 crore. The queues have vanished as have the backlogs, ensuring the poor have access to high-end technology and that too at half the rates charged by private diagnostic players. What’s more, the radiology department of the hospital even finds a place in the Limca Book of Records for handling 238 cases in 24 hours!

Philips India, in large part, can be credited with this transformation. The diversified technology company had the foresight to predict that the cash-strapped state government would not be able to invest in Philips’s modern medical equipment. At the same time, the large number of patients at the Sawai Man Singh Hospital was too lucrative a business opportunity to let go of. The company presented the hospital with a unique solution to bridge the funding gap: A public private partnership (PPP). A private player, Soni Hospital, was roped in. Soni invested the Rs 30 crore required to procure the diagnostic equipment manufactured by Philips Sawai Man Singh Hospital offered the space to set it up and also paid Soni for the scans on a ‘per use’ basis.

Philips’s role did not end there. It worked with the radiology department of the hospital to optimise the workflow and trained technicians to significantly increase the throughput. Today, on an average, 150 cases are handled by the department. The large number of patients at Sawai Man Singh also enables Soni to keep its rates low, benefiting patients in the bargain. In essence, a high volume-low margin business model was evolved.

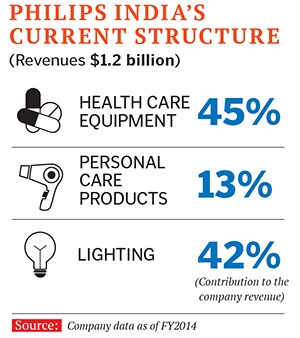

Philips is clearly changing the way it is doing business in India and its turnaround of the radiology department at Sawai Man Singh Hospital is a case in point. “We are not just a manufacturer of health care equipment and lighting products anymore, but also a one-stop-shop for all customer needs, with services at the core of this transformation,” says Krishna Kumar, vice chairman and managing director, Philips India. The company closed FY2014 with strong revenues of $1.2 billion (the company has still to release FY2015 figures). Health care equipment and consumer lifestyle businesses accounted for 58 percent of the turnover and lighting the balance, with market leadership in most of the segments it operated in. That year, the topline grew by nine percent and net profit by 71 percent. “We have never been more close to our customers,” adds Kumar.

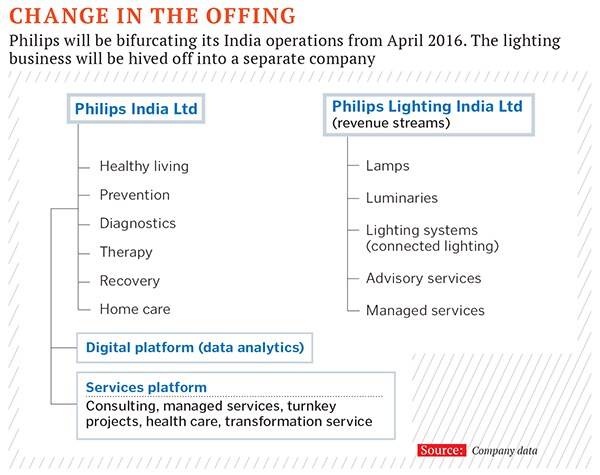

Another change in the offing at Philips will be the bifurcation of its India operations from April 2016. Philips India will house the health care equipment and consumer lifestyle businesses (the company calls this the ‘healthtech’ business) while the lighting operations will be hived off into a separate company—Philips Lighting India Ltd. “We will have two focussed companies which will invest and lead in their respective spaces,” says Kumar, who assumed a global role as head of Philips’s Emerging Health Business, based out of Amsterdam, in August. He will retain his India position till December this year.

In the run up to the move, the company has restructured its current healthtech business into six buckets and has built the digital (data analytics) and services platforms on it.

To a large extent, these changes at Philips India are necessitated by the nature of the Rs 30,000-crore Indian health care equipment market. The sector is dominated by three large multinational companies—Philips, GE Healthcare India and Siemens—which together account for a lion’s share of the high-end equipment used for MRI scans, CT scans, PET scans and cath labs. Close to 80 percent of the equipment sold in India is imported. Domestic players have a presence in the X-ray and ECG equipment segment but much to catch up with when it comes to high-end equipment. Among the three MNCs, competition is virulent and retaining market share has always been a challenge. In the 1980s, Siemens was the leader in health care equipment. GE pipped the German firm in the 1990s and, at one point, its market share was higher than the combined share of Philips and Siemens. It was only after 2010 that Philips dethroned the American company.

Having witnessed the churn, Philips is aware that it is vulnerable despite being in pole position, which explains the recent changes in its business. “Till a few years ago, Philips was a very rigid player in the market. It was always strong in terms of technology but the lack of flexibility in pricing made its products unaffordable. Once it began to look at India as a key market, things changed. It became aggressive. Today, Philips is seen as a top-end medical equipment player with competitive price points,” says Vishal Bali, former group CEO, Fortis Healthcare.

The company is today a clear leader in four of the five segments it operates in. “We have a 38 percent market share in the MRI segment, 50 percent in critical care equipment, 50 percent in cath labs and 55 percent in the home care segment,” says Sameer Garde, president, Philips Healthcare, South Asia, quoting 2014 industry data. It also has an edge in the premium ultrasound scan segment and is gaining share in CT scans and digital X-rays. “It is this hard-fought leadership that Philips is trying to retain by transforming itself,” says Bali.

Three factors, which are particular to India’s health care sector, are driving changes in Philips’s business model here. CASH-DEPRIVED SECTOR

CASH-DEPRIVED SECTOR

The first is the understanding that the health care industry here is sub-scale. However, a strong demand for health care equipment exists. “The increasing population [we add a Brazil every decade], higher life expectancy, an emerging middle class and its rising consumption, deeper penetration of health insurance coverage and growing medical tourism portend to a huge present and future demand for health care services,” says Dr Rana Mehta, partner & leader, Healthcare, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) India. “Add to that, the fact that India is simultaneously dealing with both communicable and non-communicable diseases, unlike developed nations, which handled them sequentially.”

But the surging demand remains unfulfilled. Not surprising, as India’s per capita health care spend, at $45, is way below its BRIC peers. Brazil spends $734, Russia $475 and China $169 per capita. Consequently, the beds per 1,000 population in India is a meagre 1.3 compared with Brazil’s 2.4, China’s 4.2 and Russia’s 9.7. The World Health Organization estimates the global average to be 3.5. “As much as Rs 27,000 crore is required by 2020 to bring the number of beds to China’s level,” says Kumar.

“Who will spend? India’s total expenditure [on health care] is about 5.2 percent of its GDP and only 1.2 percent of that is funded by the government. Unlike other countries, in India we are witnessing a private health care play,” says Bali. Private equity players alone have invested $3.7 billion between 2007 and 2013 in the Indian health care sector, according to PwC data. With the private sector stretched and the government constrained, pricing innovations have become crucial to grow in the market and Philips has unleashed a slew of them.

The PPP model, like in the case of the Sawai Man Singh Hospital, opened up an all new market. “This model brings in private sector capital and efficiency, uses government infrastructure and draws in modern technology to deliver equitable, affordable and quality health care,” says Chhitiz Kumar, head, Philips Capital and Business To Government and PPPs. He says this model has triggered a lot of action in Rajasthan, Gujarat, Karnataka and Haryana. Philips’s revenues through the PPP route are growing at 70 percent year-on-year, adds Chhitiz Kumar.

The other innovation is the ‘pay-per-use’ model. “The cost of health care equipment works up to 30 percent of a hospital’s project cost and if this can be eliminated through a pay-per-use basis, the initial investment costs come down dramatically,” says Bali. “The pay-per-use structure also helps hospitals price their services aggressively.”

NEED FOR LOCALISATION

The second factor driving changes at Philips is the need for local innovation. “India-focussed innovation brings down costs and gives the much-needed edge in a competitive market,” says Dr Mehta. Philips inaugurated its Healthcare Innovation Centre (HIC) in Pune in 2012 (it has another centre in Chennai catering to kitchen appliances). “HIC combines technology and market knowledge. It also helps design products that are unique to India’s needs like that of durability, higher throughput and handling voltage fluctuations,” explains Rekha Ranganathan, head, HIC. The Pune centre has so far launched five products, focusing on the twin axes of affordability and profitability. This includes the PrimaryDiagnost (a digital X-ray), the MobileDiagnost Opta (a compact and light digital mobile X-ray system where the patient need not be moved while taking X-rays), the BV Vectra (a mobile C-arm with high throughput providing high quality images) and Allura Centron (a compact multi-tasking cath lab). Products from HIC contributed to 24 percent of Philips’s growth in 2014. The company is also trying to increase its manufacturing footprint in India. “When it comes to value engineering, India is the best,” says Ranganathan. But two factors come in the way: The need for scale and the ecosystem. The Amsterdam-headquartered company is embracing a hub-and-spoke arrangement to derive the necessary scale. “Some products like BV Vectra and Allura Centron will only be manufactured in India and sent to any of the 90 countries in which Philips operates globally. This way, we will ensure the much needed scale,” she adds. India has been nominated as the global hub for Philips’s mobile surgery business.

The company is also trying to increase its manufacturing footprint in India. “When it comes to value engineering, India is the best,” says Ranganathan. But two factors come in the way: The need for scale and the ecosystem. The Amsterdam-headquartered company is embracing a hub-and-spoke arrangement to derive the necessary scale. “Some products like BV Vectra and Allura Centron will only be manufactured in India and sent to any of the 90 countries in which Philips operates globally. This way, we will ensure the much needed scale,” she adds. India has been nominated as the global hub for Philips’s mobile surgery business.

The company is also working to develop the ecosystem. “We are in the process of developing suppliers,” says Ranganathan. Here, too, the company is trying to offer volumes to suppliers by sourcing the components for use from other manufacturing facilities worldwide. But Dr Mehta feels the ecosystem will take long to develop. “China took 10 years to build what it has today,” he says.

Also, not everyone is impressed with Philips’s bet on local manufacturing. “Inverted duty structures and multiple taxes make manufacturing in India difficult. The MNCs simply import or at best assemble in India,” says Dr GSK Velu, founder and managing director, Trivitron Healthcare Pvt Ltd, one of India’s largest homegrown health care equipment companies with revenues of Rs 700 crore. “Also, bear in mind that companies like Philips and GE have made huge investments in China and hence it makes little sense for them to manufacture in India.” The Indian players have approached the government to level the playing field by removing the duty anomalies.

SHIFT TO SERVICES

The final factor driving the change is the customer who is increasingly seeking to buy the service rather than the equipment. This brings to fore Philips’s services play. “Health care services will be a Rs 1,500-crore market in five years. It is a fifth [of it] now,” says Kumar. He is aiming for a large share of this pie. The company recently launched a Healthcare Transformation Services (HTS) business. “Health care is shifting from doctor/hospital-centric to patient-centric. Also, delivery is becoming disaggregated. Single monolithic entities are giving way to small specialty hospitals. Our focus is to help hospitals change in line with these trends,” says Dr Adheet Gogate, senior director, HTS. He and his team of 10 staffers spend most of their time in hospital wards studying the process flow and finding ways to improve productivity—be it reducing the time taken to discharge a patient, increasing an equipment throughput or optimising work flow in operation theatres. “We see HTS as a change agent not just for hospitals but also for us. We sit in the trenches with our customers to understand the problem and design a solution. It offers us a big opportunity to differentiate ourselves,” Gogate adds. Philips also offers turnkey services where it designs, funds and builds an entire hospital or select departments. It even offers to manage the facilities under its Managed Services business. Home care service, for chronically ill patients suffering from respiratory and cardiac diseases, is another division the company has started.

LIGHTING BUSINESS

The focus on services extends to the company’s lighting business too. The $2 billion (around Rs 14,000 crore) lighting industry is undergoing rapid changes that make a services play critical. “Three important transformations are underway. The lighting world is fast moving from analogue to digital [from conventional lights to LEDs], connected lighting is gaining traction and lighting is no more just a utility but a lifestyle product,” says Harshavardhan Chitale, CEO, Philips Lighting Solutions. These changes throw up a huge services opportunity but he cannot put a value to the potential demand as things are at a nascent stage. Havells, Osram and Bajaj Electricals are the other major players in the market.

The LED market today accounts for a quarter of the lighting market at Rs 3,000 crore and is growing rapidly at over 100 percent. Philips is a clear market leader. “Two years ago, LED lamps contributed Rs 40 crore to the lighting business revenues. Now, it contributes a third of the revenue,” says Chitale. Shift to LEDs, he adds, has the potential to completely eliminate India’s power deficit. “The LED drive is being fuelled both by government incentives and the disincentives it imposes on conventional lamps,” says Niju V, director—automation and electronics practice, Frost & Sullivan.

Philips is exploiting the emerging service opportunity. It is offering to retrofit existing spaces with LED lamps in a manner that is cash-flow positive, balance sheet neutral and profit-and-loss account positive. The monthly savings that ensue for a customer offsets the cost of retrofitting, explains Chitale. A large IT company and a retail chain have approached the company for retrofitting. “The strong value proposition will see more opportunities here,” he says.

But this business will work only as long as LED lamps remain pricey. “It is a simple question of economics,” says Niju. “If the price of LED lamps fall, the viability of this service will be in question.”

Unlike conventional bulbs, LED lamps can be connected and operated remotely. Thus smart lighting comes into play. It is one of the five pillars of smart cities. Street lighting for an entire locality can be managed remotely and in a sustainable manner for a fee. In fact, Philips has seen customers who seek lighting as a service. “They say, ‘we need 300 lux [a measure of the amount of illumination of a surface] per square feet, for instance, and will pay on a per square feet basis every month’,” Chitale says.

Kumar is bullish about Philips’s businesses—healthtech and lighting. “Revenues will double in the next four years,” he says. Even as late as in 2000, consumer electronics accounted for 50 percent of Philips’s business in India. Lack of significant growth potential forced it to globally exit consumer electronics and focus on health care equipment and lighting. The Dutch major which globally made 48 acquisitions (between 2000 and 2010) in the health care equipment space appears to be settling down to mine more value from its two focus areas both in India and elsewhere.

First Published: Sep 29, 2015, 07:03

Subscribe Now