Distraught and disillusioned, Mazumdar-Shaw put her education to another use: Making enzymes for industrial uses. In partnership with an Irish entrepreneur who owned a company called Biocon and was looking to expand to India, she set up shop inside that hot shed. “I call myself an accidental entrepreneur," she says.

The business became successful enough that Unilever bought it in the 1980s along with its Irish parent. Mazumdar-Shaw stayed on to run the unit from Bangalore until 1998, when she and her late husband, John Shaw, bought back Unilever’s stake for about $2 million. It was a steal: She would eventually sell the enzymes business to Denmark’s Novozymes for $115 million in 2007.

By then she had bigger things in mind. In 2000, Biocon began brewing up pharmaceuticals, starting with insulin. Insulin is a type of “biologic", or a drug derived from a living source, traditionally a modified version of Ecoli bacteria in insulin’s case (Biocon uses yeast). The company’s India base enabled it to make these biologics cheaper than big Western pharma outfits.

Biologics are increasingly used to treat everything from cancer to immune system disorders. More complicated biologics like gene therapies and monoclonal antibodies are difficult to make—and extremely expensive. One drug for children with spinal muscular atrophy, for instance, costs more than $2 million for the one-dose treatment. It’s an enormous market, but exactly how big is impossible to say. Biologics accounted for $324 billion in spending at list prices in 2023, according to health care research firm Iqvia, but that number doesn’t account for the significant rebates that branded drugmakers often offer to keep their market share, lowering what insurers and patients pay but obfuscating total costs.

“These are very complex, expensive drugs, and therefore it’s important that companies like ours focus on affordable access," says Mazumdar-Shaw over tea served by a butler at her Manhattan apartment, which is adorned with landscapes by Scottish artists George Devlin and Archie Forrest.

Mazumdar-Shaw, now 72, started out in the Indian market but now sells drugs globally—and is increasingly focussed on the US and Canada, which account for 40 percent of her company’s biologics sales. She realised early that finding a cheaper way to make such complex, life-saving drugs not only made them more accessible but was also good business.

Today, Biocon, which is publicly traded in India, brings in $1.9 billion in revenue by selling dozens of generic drugs and ‘biosimilar’ medications. The company also does contract research for other companies through its publicly traded subsidiary Syngene. Mazumdar-Shaw is one of the world’s wealthiest self-made female entrepreneurs, with a fortune that Forbes estimates to be $3.2 billion.

The biggest part of her empire is a majority-owned private subsidiary called Biocon Biologics, which focuses on biosimilars and represents nearly 55 percent of the parent company’s revenue. (Indian vaccine billionaire Cyrus Poonawalla’s Serum Institute of India has a small stake in Biocon Biologics.) Akin to what generics are for chemically synthesised drugs, these cheaper alternatives mimic biologic drugs. As with generics, companies like Mazumdar-Shaw’s are allowed to develop biosimilars after a brand-name drug’s patents expire.

Though biosimilars are much more expensive to make than generics, requiring more than $100 million to develop, they can drastically reduce patient costs. Iqvia estimates biosimilars have saved the US health care system $36 billion at list prices since 2015. With 118 more biologic drugs set to lose patent protection by 2035, the market for their cheaper mimics could be about to boom.

“Even in the US now, the adoption of biosimilars is becoming far greater because health care costs are spiraling out of control, and anything you can do to rein in costs is going to be very important," Mazumdar-Shaw says, adding, “We have a huge opportunity to build a very large business."

Consider one of the company’s newest drugs: A cheaper alternative to the blockbuster autoimmune disease therapy Stelara, which was Johnson & Johnson’s top-selling drug last year, bringing in over $10 billion in revenue. Before rebates, it costs more than $25,000 per dose and is meant to be taken every eight weeks by Crohn’s disease patients and every 12 weeks by those with psoriasis. Biocon’s Yesintek, launched in February, does the same job for just under $3,000 per dose—roughly 90 percent less than Stelara.

In all, Mazumdar-Shaw’s company has debuted nine biosimilar drugs, including one that mimics AbbVie’s rheumatoid arthritis drug Humira (whose sales peaked at $21 billion in 2022) and another that’s like Genentech’s breast cancer drug Herceptin, which she launched in 2017 after a friend was diagnosed and struggled to afford the course of treatment. Herceptin cost nearly $90,000 at its peak in 2019, according to a study in JCO Oncology Practice. Seven of Biocon’s biosimilar drugs have been approved for US use.

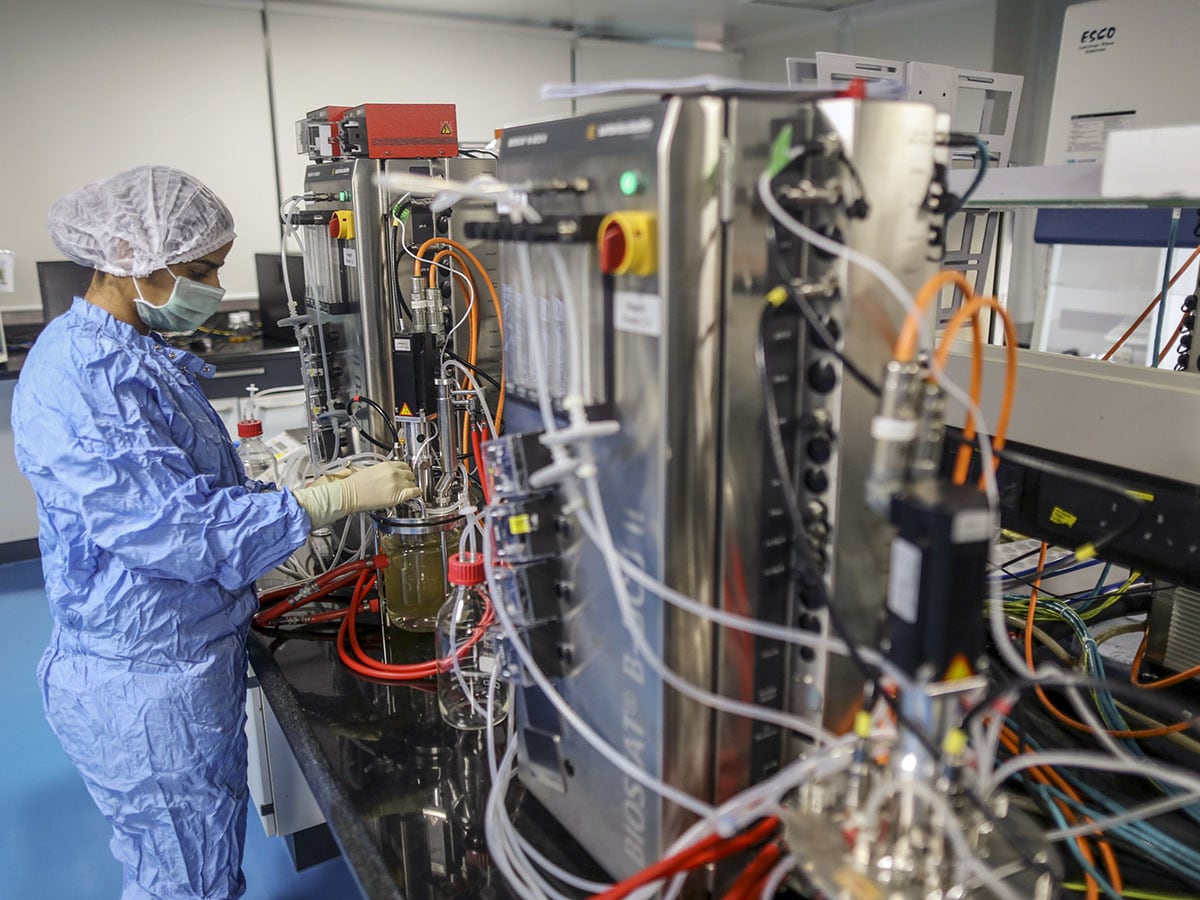

![]() Inside the research and development centre at the Biocon campus in BengaluruImage: Dhiraj Singh / Bloomberg Via Getty Images

Inside the research and development centre at the Biocon campus in BengaluruImage: Dhiraj Singh / Bloomberg Via Getty Images

Biocon Biologics is up against Basel, Switzerland–based Sandoz ($10 billion in revenue), Korean firms Samsung Bioepis (some $1.1 billion in sales) and Celltrion (around $2.5 billion in revenue) and even major pharmaceutical companies like Amgen, whose biosimilar for Stelara recorded $150 million in revenue in the first quarter. Its market share is especially high in emerging markets, in which many of its biosimilars command an 80 percent share. The American market is tougher, but it’s so much larger that even a 10 percent or 20 percent share of a blockbuster drug can be worth hundreds of millions.

One reason the US is so difficult is that drugmakers must convince America’s behind-the-scenes gatekeepers—pharmacy benefit managers—that their drugs are worth placing on the lists of approved drugs, known as formularies. With its manufacturing concentrated in India and Malaysia, Biocon must also contend with potentially large Trump tariffs (currently threatened at 25 percent) on pharmaceuticals made abroad.

“There are lots of reasons why we’ve seen it be more difficult than we’d want for biosimilars to come to market," says Benjamin Rome, a health policy researcher at Harvard Medical School, adding, “The prices for generics are much more transparent. There’s largely no rebates and no gaming there."

But Mazumdar-Shaw has a track record of overcoming challenges—and ignoring conventional wisdom. When she first decided to produce insulin in India 25 years ago, she faced a market that imported only animal insulins. Although human versions were better and available, they cost about 10 times more. “I said, ‘This is crazy,’" she recalls. “Just because we cannot afford human insulin, we are having to use animal insulin, so let me do something about it." At the time, Biocon was still making industrial enzymes and had no experience in the drugmaking business. But within four years, it had developed India’s first human insulin, making it possible for millions of diabetics who needed insulin treatment to get better drugs. “That is what then gave me the raison d’àªtre to focus on biopharmaceuticals," she says.

Today, Biocon has 20 drugs in oncology, immunology, diabetes and ophthalmology either on the market or in the works globally. It also introduced its first GLP-1 biosimilar for diabetes and obesity in the UK and anticipates coming to the US when popular drugs like Ozempic come off patent.

Mazumdar-Shaw is confident she can commercialise a drug every year in the US or Europe from now until 2030. Biocon plans to launch a biosimilar to Regeneron’s blockbuster eye disease drug Eylea ($10 billion in 2024 sales) later this year. She was hoping to spin off Biocon Biologics into a separate public company in the next 18 months, but with a volatile stock market she is mulling other options.

“I believe we are in a humanitarian business," she says, “and I think we are doing our bit for affordable access, which is what we want."