Red Emmerson: The last timber baron

From humble beginnings traipsing through California's vast forests with his dad, he has built a multibillion-dollar logging fortune by being cheaper and more aggressive than anyone else

Red Emmerson

Red Emmerson

Image: Tim Pannell for Forbes

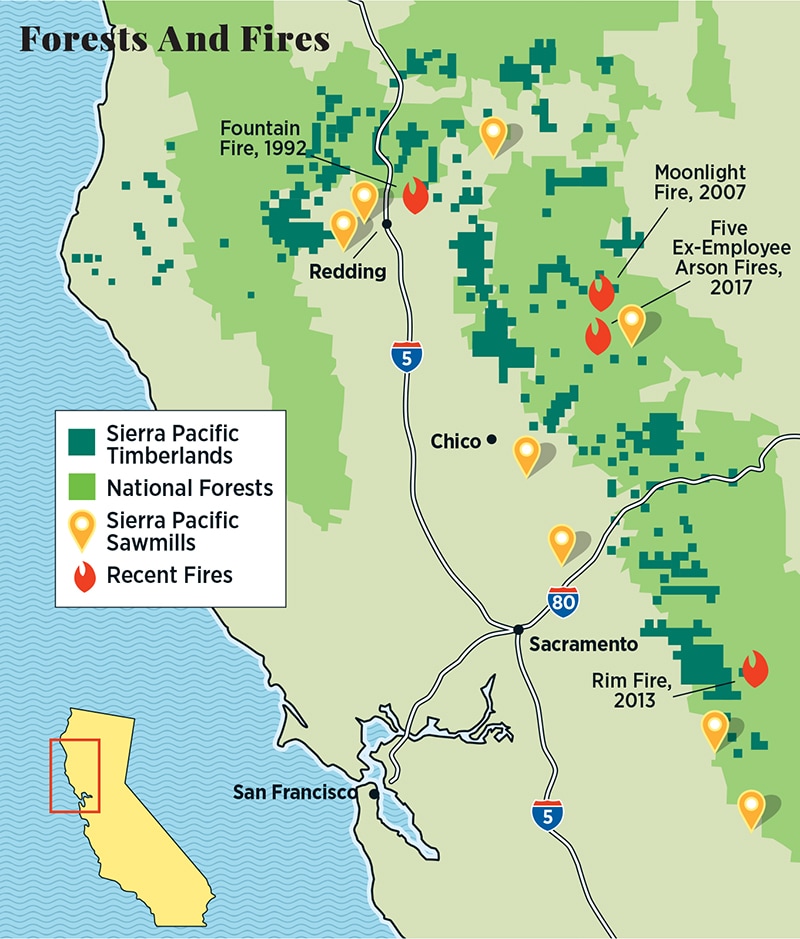

One of the largest fires to burn in California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range, the Rim Fire tore through 257,000 acres on the edge of Yosemite National Park in 2013. Not long after firefighters doused the flames, a fleet of bulldozers and trucks arrived, sent by billionaire Archie Aldis “Red” Emmerson. Workers began ripping up the trees even as the brush nearby was still smouldering.

“We’ll be in there before the smoke is out,” Emmerson boasts in a rare, three-hour interview from his Douglas-fir-panelled boardroom in tiny Anderson, California, which is wedged between the Shasta-Trinity and Lassen National Forests, about two hours north of Sacramento. Emmerson recalls the Fountain Fire of 1992 in Shasta County, 50 miles northeast of Anderson, that burnt 64,000 acres and 272 homes: “We had trucks coming down the road that had flames on the back.” At 89 years of age, he walks slowly but has no problem piloting his silver Dodge pickup truck to work before 8 am, six days a week. Adds his son Mark, who is CFO, “We get in, and we are very aggressive after a fire.”

Nicknamed “Red” as a teen for his hair colour, Emmerson is happy to reminisce about the many fires from which his Sierra Pacific Industries has profited. Wearing jeans held up by a belt buckle emblazoned with the insignia he brands on his ranch’s cattle, the feisty tycoon, who runs the business with his two sons, George, 61, and Mark, 58, makes more money from logging after forest fires than any person in America. When the government sells contracts to cut down trees after fires in national forests—a controversial practice known as post-fire salvage logging—Emmerson buys in at a steep discount, often paying one half to one fourth the price for traditional wood. Sierra Pacific then turns the usable lumber (about 90 percent) into boards and other wood products to sell to homebuilders and lumber retailers like Home Depot, Menards and Lowe’s.

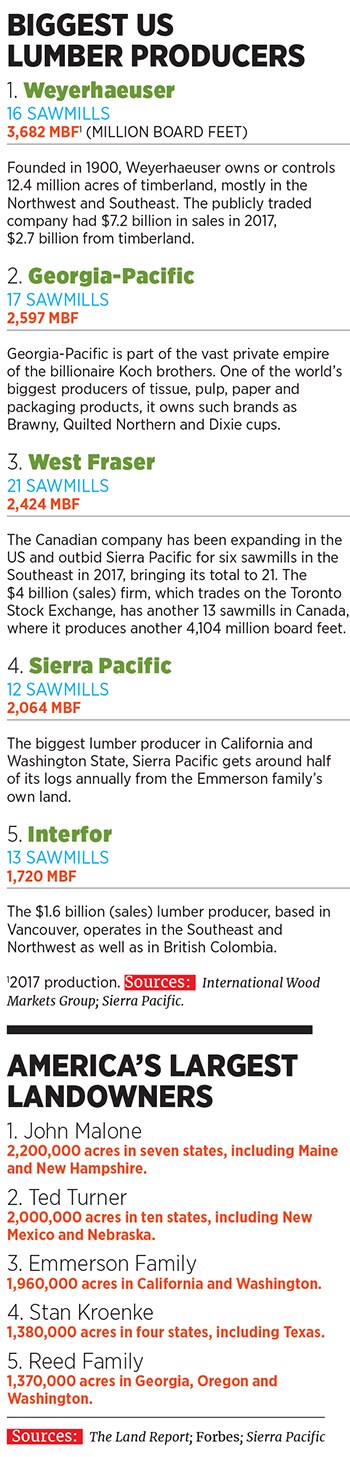

Sierra Pacific has little competition, thanks to a 1990 law that prohibits bidding from any lumber companies that export logs. That eliminates rivals like publicly traded Weyerhaeuser and Rayonier as well as big Canadian firms.

It’s a profitable niche. While Emmerson refused to comment on his company’s finances, Forbes estimates that Sierra Pacific, which Emmerson owns entirely with his two sons and daughter, has operating profits (before adding back depreciation and amortisation) of approximately $375 million annually on sales of $1.5 billion. Salvage timber, which it sometimes buys for pennies on a dollar, is a significant contributor. Based on an analysis of records obtained in a Freedom of Information Act request, Forbes estimates that Sierra Pacific’s operating profit margin for products made from salvage logs can be as high as 40 percent and contributed as much as $100 million at its peak in 2015.

Salvage logging is just one extreme example of how Emmerson has built his lumber business over nearly seven decades. From buying spare parts for his sawmills at bankruptcy auctions to aggressively acquiring California land when other timber companies were selling, Emmerson has successfully carved out a fortune by being opportunistic and cheap. That has enabled him to become America’s richest lumberman—worth more than $4 billion—and, in these times of increased scrutiny and globalisation, the nation’s last great lumber baron. “It is better than I ever thought it would be,” Emmerson says. “Because the trees will grow, and they get bigger.” Sierra Pacific cleared many trees in the Stanislaus National Forest and its own neighbouring land after the Rim Fire burnt close to 260,000 acres in 2013. The company could head back soon: The Trump Administration just approved a $28 million reforestation plan that will include clearing more trees in the area

Sierra Pacific cleared many trees in the Stanislaus National Forest and its own neighbouring land after the Rim Fire burnt close to 260,000 acres in 2013. The company could head back soon: The Trump Administration just approved a $28 million reforestation plan that will include clearing more trees in the area

Image: Justin Sullivan/ Getty Images

Over the decades, Emmerson has amassed more timberland in California than anyone else. He is the third-largest landowner in America, behind billionaire conservationists John Malone and Ted Turner, according to The Land Report. Overall, Sierra Pacific is the fourth-largest lumber producer in the US. The company gets around 70 percent of its annual revenue from the sale of lumber. In California, about half comes from logs cut down on its land and 16 percent from logs in national forests, much of which is salvaged wood. Sierra Pacific also operates a millwork division, which makes door frames and mouldings, and a manufacturer of high-end, custom-built windows. Together the two divisions bring in roughly $400 million in sales.

While Emmerson’s resourcefulness has helped him climb into the top ranks of the world’s wealthiest, critics say these riches have come at the expense of the environment and taxpayers. More than 250 scientists signed a letter asking Congress to protect forests from post-fire logging, saying that it “can set back the forest renewal process for decades”. That’s because it strips the land of nutrients, preventing it from regenerating. Not only is the carbon stored in the charred tree trunks not reabsorbed by the soil—worse, it is released into the atmosphere as greenhouse gas.

“It’s a degraded landscape,” says Chad Hanson, a scientist who studies post-fire logging and whose non-profit John Muir Project has won injunctions against four Sierra Pacific post-fire contracts. “Fire is not the thing that’s creating areas of devastation and wastelands. It’s logging, especially post-fire logging.”

Sierra Pacific rejects the scientists’ analysis, arguing that the process can speed up recovery. “It’s about extracting the value we can from a bad situation,” says a company spokesperson.

Regardless, logging in national forests is costly for taxpayers, says Hanson, who estimates they are on the hook for $1 billion a year, at least $500 million of which is directly related to post-fire salvage. That’s the amount the government pays to build roads to remote areas destroyed by fires and for herbicides the forest service sprays prior to logging to make clear-cutting easier, among other costs. Meanwhile, the federal government pulls in about $150 million annually from selling the timber in national forests, about one fourth of which comes from post-fire logging. “It’s a bad deal financially for taxpayers, but it’s a great deal for the mills,” says economist Ernie Niemi, who has studied the impact of forest management since the 1970s. “It’s very hard to justify any salvage logging. It’s like they’re bandits.”

*****

In 1948, he purchased a yellow Ford convertible and drove down to California, where his father had a portable sawmill that he wheeled through forests. In 1951, Emmerson and his father built a sawmill in Arcata, a town not far from Redwood National Park. The next year Emmerson was drafted into the Korean War. While he was away, Curly’s drinking habits put the sawmill in jeopardy of closing. When Emmerson got back, he took over and turned it around, investing in better equipment and adding a second production shift. For many years he worked seven days a week. For exercise, he chopped wood. “We didn’t have any money. We didn’t have any timberland. We were the poor guys,” Mark says.

The 1960s brought on a short-lived partnership with another father-son firm, Mike and John Crook. In 1969, their joint venture had $38 million in sales—$263 million today—and they took it public at the time, Emmerson was president, John Crook was executive vice president, and each owned 40 percent. Five years later the partnership dissolved. Crook had wanted Sierra Pacific to become a retailer for builders and do-it-yourselfers, and vetoed buying more land. Emmerson took the company private, buying out Crook and the other shareholders for $38 million. Free to buy timberland, Emmerson soon amassed around 150,000 acres, though most of Sierra Pacific’s logs still came from national forests. At the time, public pressure from environmental groups to reduce sales from national forests was mounting. Worried about tightening regulations, timber companies like his frantically bid on government logs while they could, driving up prices and throwing the economics out of whack. In 1980, amid the buying frenzy, Sierra Pacific purchased 73 percent of its timber from the government and lost $13 million.

But there was a silver lining. The high timber costs drove rivals out of regulation-heavy California. In 1988 Santa Fe Southern Pacific Corp sold 522,000 acres of prime timberland to Sierra Pacific for $460 million. The Santa Fe deal turned Sierra Pacific into the biggest timberland owner in California. “Bank of America gave us credit for half a billion dollars,” recalls Emmerson. “And it’s more than we deserved. It was a monstrous deal for us. Today that land is worth, I think, three times what we paid for it.” Over the next decade, Sierra Pacific purchased 800,000 more acres from Georgia-Pacific, among others. It now has 1.68 million acres in California and 291,000 in Washington State.

Even with its massive landholdings, Sierra Pacific relies on national forests to supplement the timber from its own land, at a time when the federal government sells less than one fourth of what it did four decades ago. Over the past seven years, around 16 percent of Sierra Pacific’s California timber has come from US Forest Service land. That’s one reason why Emmerson turned to salvage logging after fires or insect infestation. In 2015, at the peak of California’s drought, the company acquired 58 percent of its federally sourced logs through post-fire salvage logging. In 2017, it was 19 percent.

Sierra Pacific has also stacked the deck in its favour by building a dominant network of sawmills in northern California. It now has ten mills there, at eight locations, and they are all close to federal forests. No one else owns more than three. Even if smaller rivals win post-fire contracts, they often end up reselling to Sierra Pacific, which gets around 31 percent of its California timber indirectly. “We have somewhere to take it,” Emmerson says.

*****

To Emmerson, post-fire logging is just another form of his legendary bargain hunting. Even as his business grew, he flew coach, stayed at the cheapest motels and ate lunch packed by his wife, Ida, while on the road. “Limos” kept at airports for employees became a running joke: One car had a mushroom growing in the backseat another had a gaping hole in the floorboard. The limos routinely lacked power steering, modern brakes and air-conditioning.

The company is just as scrappy today. Sierra Pacific often buys whole pallets of used steel and spare parts, like motors, car batteries and farm tools, at bankruptcy auctions or on eBay for its own fabrication shop to reuse. The IT guys buy old computer parts online. Because it picks up so much in bulk at auctions or through bankruptcies, Sierra Pacific has set up an eBay store to sell the parts it doesn’t use. “We bought an airplane that was sitting in Russia for two years. We bought it for the parts,” says Mark, who joined the company in 1985. Adds his older brother, George, who is president: “A lot of our competitors don’t do that kind of stuff.”

undefinedSierra Pacific has operating profits of approximately $375 million annually on sales of $1.5 billion[/bq]

Being thrifty and aggressive has helped build the business, but it has also created plenty of challenges, including dozens of lawsuits. The biggest one it’s ever faced resulted in a record $122.5 million settlement. The Department of Justice (DOJ) alleged in 2009 that Sierra Pacific’s negligence helped lead to the Moonlight Fire, which burnt 46,000 acres in Lassen and Plumas National Forests two years earlier In the summer of 2007, Sierra Pacific hired a small firm owned by one person, called Howell’s Forest Harvesting, to log in that area. A bulldozer brought in and operated by Howell’s allegedly struck a rock and caused a spark. The loggers left without checking the site for flames or smoke, even though it was a “red flag” day, meaning high fire potential, according to the government report. A bigger red flag, the DOJ argued, was that Howell’s equipment had already started three other fires that summer, at least one of which Sierra Pacific allegedly knew about, raising questions about why Sierra Pacific was working with the firm. The DOJ’s lawsuit against Sierra Pacific, Howell’s and other, much smaller parties sought close to $800 million in damages for negligence. In 2012, Sierra Pacific and the others entered into a voluntary settlement, agreeing to pay $55 million and forfeiting 22,500 acres to the federal government but not admitting any wrongdoing. Emmerson’s portion: $47 million and all the land. “We had a gun to our head,” says Mark, who thinks the company was targeted for being so rich and successful. Sierra Pacific is appealing to the Supreme Court. It thinks it has a chance because a California court ruled in its favour in 2013 in a related case and ordered the state’s Department of Forestry & Fire Protection to pay the defendants about $30 million. The judge ruled that the investigation was “corrupt and tainted” and that the prosecution “destroyed critical evidence... and engaged in a systematic campaign of misdirection with the purpose of recovering money from the defendants.” That case is ongoing. “It’s pathetic. Stuff like this, it’s just demoralising and it’s wrong,” Red Emmerson says. “But I’m sick of it. Let’s go run our business.”

Sierra Pacific is appealing to the Supreme Court. It thinks it has a chance because a California court ruled in its favour in 2013 in a related case and ordered the state’s Department of Forestry & Fire Protection to pay the defendants about $30 million. The judge ruled that the investigation was “corrupt and tainted” and that the prosecution “destroyed critical evidence... and engaged in a systematic campaign of misdirection with the purpose of recovering money from the defendants.” That case is ongoing. “It’s pathetic. Stuff like this, it’s just demoralising and it’s wrong,” Red Emmerson says. “But I’m sick of it. Let’s go run our business.”

The problems aren’t just with contractors. An hourly employee who worked for Sierra Pacific for over a decade was convicted of starting five fires in a national forest last summer. He pleaded guilty and was sentenced in November to 20 years to life in prison and ordered to pay a $25.2 million fine. Sierra Pacific was not implicated in the case. The culprit gave no reason for his actions, but the conviction highlights a dirty secret of the industry: Sawmill workers, who often rely on overtime, can benefit financially from forest fires. The other dirty secret is that local forest service officials, who decide whether to sell the salvaged wood, benefit from the sales. Proceeds from such sales typically go to regional offices. Once debts tied to salvage logging are paid off, the offices can use what’s left to pad their budgets.

It’s not just the forest fires that have gotten Sierra Pacific into hot water. It has been sued at least 19 times for its logging practices but says it has not lost a case. It hasn’t been so lucky defending its sawmills. In 2007 Sierra Pacific paid $13 million to settle a lawsuit involving four of its mills with California’s air quality regulator. The agency claims it operated without air-pollution-control equipment and falsified reports to conceal the violations. (Sierra Pacific says it self-reported the issue.) In 2016 the company settled two other lawsuits that related to Clean Water Act violations due to illegal runoff from some sawmills.

“There’s harvest rules, Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act,” says Emmerson, whose daughter-in-law worked at the Environmental Protection Agency under George W Bush and now lobbies for a different timber company. “They’re all with good purposes, but the environmental community uses them as obstructionist tactics to stop things from happening.”

But the political winds are changing, with the climate in Washington becoming more favourable. Donald Trump’s administration has rolled back protections on federal land and recently approved a $28 million reforestation plan that will include clearing more trees on land burnt in the Rim Fire.

Still, Sierra Pacific is looking to push beyond California to places where it might not have to spend so much time fighting environmentalists and bureaucrats. In 2017 it tried to acquire six sawmills in Georgia and Florida but lost out to a publicly traded Canadian firm. It has been more successful expanding in Washington State, where Sierra Pacific has invested more than $1 billion, largely on timberland and four sawmills. In late 2016, Sierra Pacific opened a $100 million mill in Shelton. (Despite his record investment, Red’s thriftiness is on display: Nearly every staircase is recycled from an old sawmill.) The company says it is simpler and quicker to cut in Washington than it is in California. Sierra Pacific is now the largest lumber producer in the state, which has been home to publicly traded timber giant Weyerhaeuser for 118 years. Sierra Pacific is able to cut away in Weyerhaeuser’s backyard due in part to regulations that prohibit exporting companies from buying logs from state or federal forests.

Emmerson, who is still involved in the company’s strategic direction, spends much of his time now looking for timberland acquisitions and infrastructure investments. Recent projects include the opening of a new manufacturing plant in Red Bluff, California, and the $60 million rebuilding of a sawmill in Burney, California.

Emmerson may be old, but he isn’t ready to step away. “Red doesn’t work as much as he used to. Sometimes he’s not here on Sunday. And that’s about the truth,” Mark says. Emmerson responds with a laugh: “[My children] are better educated, better organised than I ever was. And smart. But I still think there’s some things I can do pretty good...&thinspI’m very optimistic about the future.”

First Published: Jul 24, 2018, 10:24

Subscribe Now