The inside secret of In-N-Out's success

The US burger chain is a culinary anachronism that commands immense loyalty

Lynsi Snyder stands outside a replica of In-N-Out's original hamburger stand in Baldwin Park, California

Image: Ethan Pines

Hamburger Lane is a quarter-mile, palm-lined stretch of Baldwin Park, California, 30 minutes east of Los Angeles. Halfway down the block, a low-slung building covered in grey siding sits behind a security fence. Knowing what’s inside the little structure helps explain the street’s unusual name. It’s the top-secret corporate test kitchen for In-N-Out Burger, the iconic West Coast chain.

Lynsi Snyder, the company’s billionaire president, hovers over a set of double fryers and stove-top griddles. “To be honest, I don’t come here a whole lot,” she says. Given the clean counters and neatly tucked-away cooking utensils, it doesn’t look like anyone comes here often.

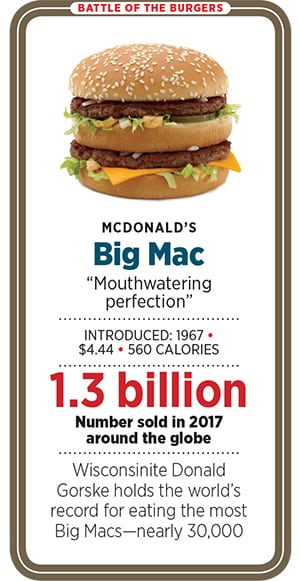

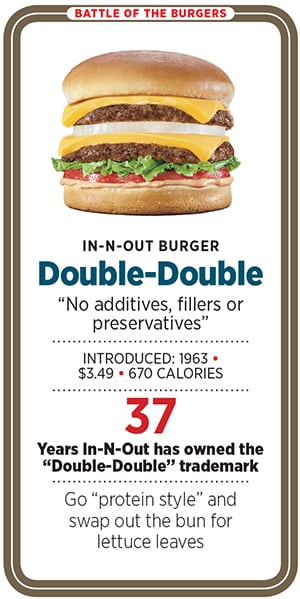

Which is probably not far off the mark. While McDonald’s and Burger King serve well over 80 different items, In-N-Out famously serves fewer than 15: Burgers, cheeseburgers, fries, soda, milk shakes and the signature two-patty Double-Double. Snyder has added just one thing: Hot chocolate in 2018. The company will make tweaks from time to time, like switching to a premium Kona coffee and healthier sunflower oil for cooking fries.

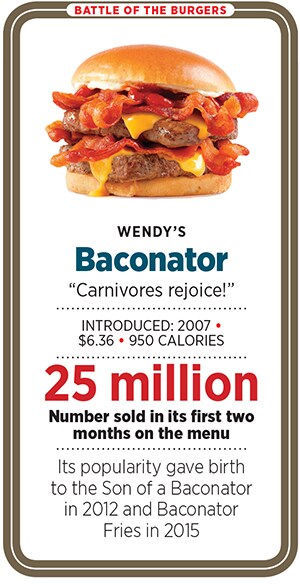

But Snyder, who at 36 debuts on this year’s Forbes 400 as its youngest woman, with a net worth of $3 billion, fiercely embraces an imperviousness to change. “It’s not [about] adding new products. Or thinking of the next bacon-wrapped this or that. We’re making the same burger, the same fry,” says Snyder, wearing black lace-up combat boots and stacks of silver bracelets on both arms. “We’re really picky and strategic. We’re not going to compromise.”

In-N-Out is a culinary anachronism. It hasn’t evolved much since Snyder’s grandparents founded it in 1948. Buns are baked with slow-rising dough each morning. Three central facilities grind all the (never-frozen) meat, delivering daily to the 333 restaurants. Nearly all its locations are in California, and all are company owned. (In-N-Out does not franchise.) Heat lamps, microwaves and freezers are banned from the premises. The recipes for its burgers and fries have remained essentially the same for 70 years.

Harry Snyder, the co-founder of In-N-Out

Consistency has earned it a passionate following. In-N-Out has become a fixture at Oscars after-parties. Its secret menu, like the option to order a burger “protein style”—lettuce leaves, no bun—is the least well-kept secret since the WikiLeaks cables. Top chefs like Gordon Ramsay, David Chang and Thomas Keller are all enthusiastic fans. The actor-cum-rapper Donald Glover has rhapsodised about In-N-Out in his lyrics. And in 2006 Paris Hilton got a DUI because, as she later explained, “I was just really hungry, and I wanted to have an In-N-Out burger.”

“They have a loyalty and an enthusiasm for the brand that very, very few restaurants can ever obtain,” says Robert Woolway, who handles restaurant deals for the Los Angeles-based investment bank FocalPoint Partners.

That loyalty is lucrative. An In-N-Out store outsells a typical McDonald’s nearly twice over, bringing in an estimated $4.5 million in gross annual sales versus McDonald’s $2.6 million. (In-N-Out, which is private, won’t comment on its financials.) In-N-Out’s profit margin (measured by earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) is an estimated 20 percent. That’s higher than In-N-Out’s East Coast rival Shake Shack (16 percent) and other restaurant chains that typically own their locations, like Chipotle (10.5 percent). Revenue should surpass $1 billion this year, roughly doubling in eight years, and the business is debt-free, according to the company. In-N-Out is conservatively worth $3 billion, and Snyder now owns virtually all of it after receiving chunks on her 25th, 30th and 35th birthdays (she got the last slice in 2017).

Snyder is an unlikely shepherd of her family’s business. By all rights, her uncle should be running In-N-Out, if not for his untimely death. She never graduated from college and lost her father to drug abuse. As a young woman, she battled through a period of alcohol and drug use and three divorces. Snyder, a devout Christian who sports tattoos of Bible verses, came out of those experiences drawn to In-N-Out’s long-standing stability—determined to change the company as little as possible, particularly the brand’s image of 1950s wholesomeness. After taking over in 2010, she embarked on a slow, steady expansion across the West, opening more than 80 stores in the same period that Five Guys, a close competitor, added more than 500 across America.

“I felt a deep call to make sure that I preserve those things that [my family] would want. That we didn’t ever look to the left and the right to see what everyone else is doing, cut corners or change things drastically or compromise,” says Snyder, who has spoken with the media only a handful of times. “I really wanted to make sure that we stayed true to what we started with. That required me to become a protector. A guardian.”

*****

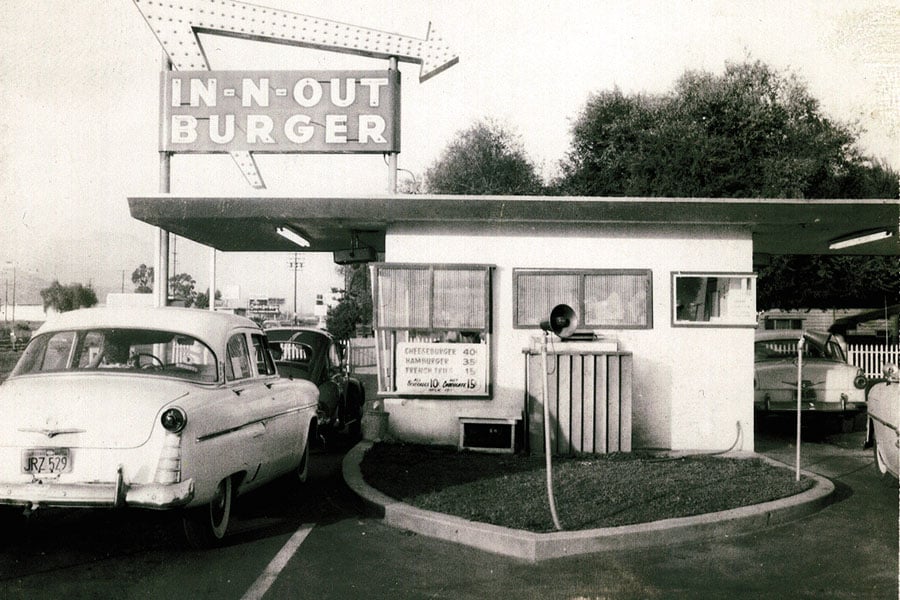

In 1948, Harry and Esther Snyder, Lynsi’s grandparents, opened the first In-N-Out, in Baldwin Park. It had no indoor seating, so Harry installed a two-way speaker box connected to the kitchen, creating an early drive-thru window. As Americans flooded the new US highway system, In-N-Out, which was placing its restaurants alongside the new roads, took off. In southern California, In-N-Outs became a hangout for hot rod racers. From the early days, Harry and Esther were keen to keep as many aspects of the business in-house as they could. They butchered their own meat, started a wholesaling firm to stock up on paper supplies and used their own construction crew to build new stores.

The original In-N-Out in Baldwin Park, California, had no inside seating. On Day One, it sold 57 hamburgers

The original In-N-Out in Baldwin Park, California, had no inside seating. On Day One, it sold 57 hamburgers

In-N-Out grew gradually, reaching 18 locations, all in California, by the time Harry died in 1976. His younger son, Rich, took his spot the elder son, Guy, Lynsi’s father, had been passed over. He had an ongoing problem with opioids after a motorcycle accident left him with chronic pain. He spent his days away from the company, drag racing or on his 115-acre ranch in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, where Lynsi grew up.

In December 1993, Rich flew to see his niece Lynsi in a play at a private Christian school and then continued on to the opening of store No 93 in Fresno, California. On the way home, the ten-passenger plane crashed, leaving no survivors. After his death, Esther became president, and Guy, who had separated from Lynsi’s mother earlier that year, took over as executive vice president and chairman.During Guy’s six years as chairman, In-N-Out grew to 140 stores, with over $200 million in revenue. Yet he struggled personally. On Christmas in 1995, he was arrested for public intoxication and illegally carrying a loaded firearm, which he had along with a switchblade knife and marijuana. Over the next few years he survived a drug-related heart attack and three drug overdoses before dying of heart failure (with hydrocodone in his system) in December 1999, at the age of 48.

“When he was sober, he was the best dad in the world. We had our time cut short,” says Lynsi, who has a scroll with the words “Daddy’s Girl” tattooed on her right shoulder.

Before her father died, Lynsi had worked for a few months at an In-N-Out in Redding, California, separating leaves of lettuce and working the register. Soon after, the 18-year-old married and moved close to the company’s headquarters in Baldwin Park to take a job at In-N-Out’s corporate merchandising department, approving projects like T-shirt designs. Lynsi fell into a year-long stretch of alcohol and marijuana use, and she and her husband divorced after a few years. A second short-lived marriage followed.

“It was like a black-sheep era of my life,” she says. “By the time I hit 22, it was pretty much over.”

Lynsi rotated through departments at In-N-Out to learn the business. As Lynsi educated herself on how it worked, Esther, then in her 80s, ran day-to-day operations. Then Esther died too, in 2006.

Mark Taylor, a longtime In-N-Out executive (who is also Lynsi’s brother-in-law), became company president, turning over the role to Lynsi in 2010. At 27, Lynsi was running In-N-Out, which was generating an estimated $550 million in sales at 251 locations. Her third marriage came soon after, this time to a race car driver. (It’s in the blood: Lynsi also drag races competitively.) They divorced in 2014, followed by her fourth marriage. “The things that I’ve been through forced me to be stronger,” she says. “When you persevere, you end up developing more strength.”

Her third marriage came soon after, this time to a race car driver. (It’s in the blood: Lynsi also drag races competitively.) They divorced in 2014, followed by her fourth marriage. “The things that I’ve been through forced me to be stronger,” she says. “When you persevere, you end up developing more strength.”

*****

An In-N-Out restaurant is a time capsule. The red-and-white colour scheme hasn’t changed since the 1950s, and the chrome tables and vinyl chairs are poodle-skirt-era throwbacks. Palm trees are a frequent motif—printed on the company’s plates, painted onto restaurant walls—a nod both to In-N-Out’s California roots and to Grandpa Snyder’s favourite movie, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World, from 1963. Bible verse numbers have appeared on burger wrappers and cups since 1985, and Snyder has added two more: Proverbs 24:16 (for those unfamiliar: “...the wicked shall fall into mischief”) to the fries container and Luke 6:35 (“But love ye your enemies, and do good”) to coffee cups.

Over the past 30 years, the price of the Double-Double hasn’t even kept up with inflation. In 1989 the sandwich cost $2.15, or about $4.40 in current dollars. It costs $3.85 today. A combo meal (Double-Double, fries, drink) goes for $7.30, compared with $10.94 for Shake Shack’s standard double-burger patty and fries.So how does In-N-Out maintain its margins? To start, the limited menu means reduced costs for raw ingredients. The company also saves money by buying wholesale and grinding the beef in-house. By doing its own sourcing and distribution, it likely saves 3 percent to 5 percent in food costs a year. It cuts out an estimated 6 percent to 10 percent of total costs by owning most of its properties—many bought years ago—and not paying rent. In-N-Out picks its locations carefully, clustering them near one another and close to highways to lower delivery costs while also avoiding pricey urban cores. It has just one location within the city limits of Los Angeles and one in San Francisco, while many Shake Shacks are smack in the centre of town.

While much has stayed the same at In-N-Out, Snyder has made some changes. She moved the company into Texas for the first time in 2011 and into Oregon four years later. Last November, In-N-Out announced it would expand to Colorado—once it finishes building a new regional headquarters and a patty-making facility there, likely by 2020. New Mexico may be next, a few years after Colorado, Snyder says, since the new supply centre is nearby. Snyder still abides by the long-standing In-N-Out rule that all new restaurants fall within a day’s drive from the nearest warehouse, so meat and other ingredients stay fresh.“I don’t see us stretched across the whole US. I don’t see us in every state. Take Texas—draw a line up and just stick to the left. That’s in my lifetime,” Snyder says. “I like that we’re sought after when someone’s coming into town. I like that we’re unique. That we’re not on every corner. You put us in every state and it takes away some of its lustre.”

No matter where In-N-Out goes, it has to deal with competitors with entrenched positions. In Texas it faces 68-year-old Whataburger. The $2-billion-in-revenue company has 674 locations in the Lone Star State—In-N-Out has just 36 there—after opening 116 more in Texas since In-N-Out came in. “Certainly we’d love for them to go somewhere else. But they’re welcome to compete,” says Preston Atkinson, Whataburger’s CEO. “They’re doing something different than we are. In-N-Out has got a limited menu.” But In-N-Out is betting that its small number of offerings and higher-quality food will help win over Whataburger customers. It has launched a highway billboard campaign outside Dallas—where Whataburger has 20 percent of its stores—with the tagline “No Microwaves, No Freezers, No Heat Lamps.”

On its California home turf, In-N-Out must defend against incursions. Shake Shack, the popular $359-million-in-sales burger chain founded by the New York restaurateur Danny Meyer, has come west, opening nine locations in southern California during the last two years, with plans to open three in the Bay Area starting this fall. Shake Shack burgers, made with meat from the famous high-end butcher Pat LaFrieda and served on potato-bread buns from Martin’s, have their own loyal following. “We wanted to bring our own spin to California,” says Andrew McCaughan, Shake Shack’s vice president of development. “It’s absolutely a key market for us, and we continue to really want to invest deeper and deeper in the market.”

At In-N-Out, Snyder’s “goals are not for us to be the biggest”, says executive vice president Bob Lang, a 45-year In-N-Out veteran. “Really, it’s about maintaining the legacy of her family and a family environment.”

Snyder is popular with her 26,000 employees. She has a 99 percent approval rating on Glassdoor.com, the job-reviews site, and is ranked No 4. on a 2018 Glassdoor list of top bosses at large companies, ahead of CEOs like LinkedIn’s Jeff Weiner, Salesforce’s Marc Benioff and Microsoft’s Satya Nadella.In-N-Out and Snyder get high marks for a reason: Good pay and career development. Restaurant workers, or “associates” in In-N-Out speak, make $13 an hour, versus the $9 to $10 or so that’s typical at most national competitors, including McDonald’s and Burger King. Part- and full-time restaurant workers can enrol in dental, vision and life insurance plans through the company, and full-timers can get health insurance and paid vacation, accruing time off after two weeks of employment.

The average In-N-Out manager has been with the company for 17 years and makes $163,000, more than the typical California dentist, accountant or financial advisor. Managers get profit-sharing, too. “They’re simulating an ownership mentality at the restaurant,” says John Glass, a restaurant-industry equity analyst at Morgan Stanley. “That manager now has skin in the game.”

*****

Back when he was chairman, Rich Snyder summed up the thought of selling In-N-Out this way: “I would be prostituting what my parents made by doing that,” he told Forbes in 1989. “There is money to be made by doing those things, but you lose something, and I don’t want to lose what I was raised with all my life.”

Over the course of a month, Lynsi Snyder routinely gets offers to take In-N-Out public or sell. “We’ve had some pretty crazy offers,” says Snyder. “There’s been, like, princes and different people throwing some big numbers at us where I’m like, ‘Really?’” The plan never changes. “We will continue to politely say no to Wall Street or to the Saudi princes. Whoever will come,” says Arnie Wensinger, In-N-Out’s longtime general counsel.

The idea of an In-N-Out IPO leaves bankers like Damon Chandik, the head of Piper Jaffray’s restaurant M&A team, salivating. “I get calls all the time on In-N-Out. It would be the hottest IPO out there,” he says. “I admire her and the whole company for not going down the path. You do have that risk of ultimately changing the culture of the business.”

Given the investor appetite for Shake Shack, whose stock trades at almost 100 times earnings, a public offering would undoubtedly hand In-N-Out tens, if not hundreds, of millions of dollars in working capital—and give Snyder a way to cash out part of her stake in the business.

“It’s not about the money for us,” she says. “Unless God sends a lightning bolt down and changes my heart miraculously, I would not ever sell.”

First Published: Nov 19, 2018, 15:17

Subscribe Now