'Indian cuisine needs to be catalogued': Garima Arora

Garima Arora, the country's first woman chef to win a Michelin star, is kickstaring an initiative to rebrand Indian food for the global audience, called 'Food Forward India'

Garima Arora

Garima Arora

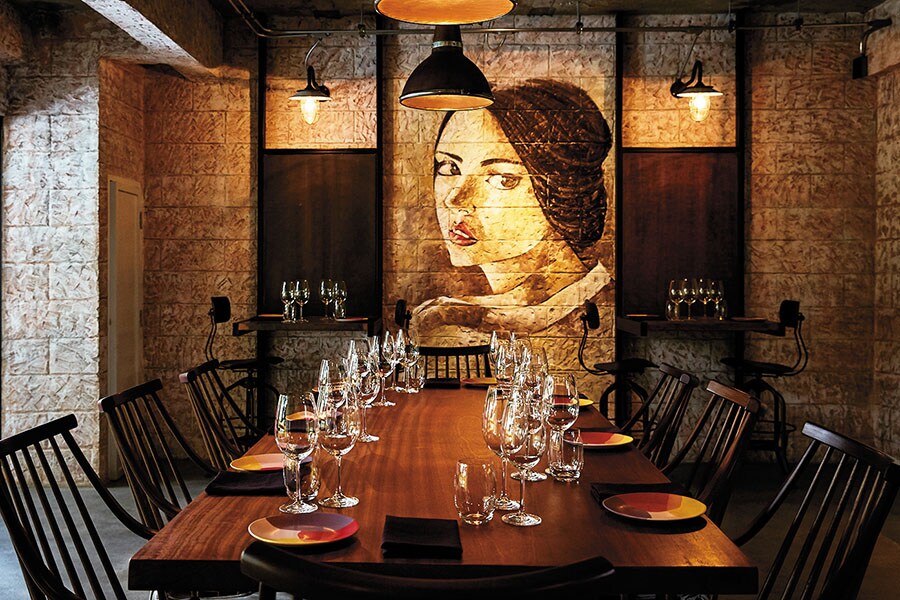

Image: Panya Leardvisetkul[br]At her Michelin-starred restaurant Gaa in Bangkok, Garima Arora has drawn from her Indian roots and techniques to elevate dining to global standards, becoming the first Indian female chef to earn the prestigious star rating. Now, Arora, 33, wants to further the conversation through Food Forward India, a not-for-profit initiative that will bring together multiple stakeholders of the food and beverage industry to find ways in which to reimagine Indian food for the world “minus any presumptions”. Ahead of the first chapter that will take place in Mumbai on October 17, Arora tells Forbes India what she intends to achieve. Edited excerpts:

Q. What is the trigger for the Food Forward India initiative and what sort of platform will it be?

For the longest time, people were asking what we would do in India. It started with people asking us to do four-hands dinners and pop-ups, but we wanted to do something more meaningful, something that would take the focus a little away from what we do at Gaa to the larger picture. The way we are looking at it is an afternoon of good conversation about Indian food, what we understand of it, and how people around the world understand it. We are going to start out without any presumptions, and hear what everyone—colleagues, culinary professors, food scientists, students and historians—have to say, and hopefully together we can come up with a narrative that we can promote internationally.

Q. You’ve mentioned the initiative would re-evaluate and re-examine Indian food. Why does Indian food need to be relooked at?

Over the last year and a half, since we’ve gotten so much attention from the world media, I figured what they understand of Indian food is really primitive and superficial. For them, Indian food is nothing beyond naan and curry. They haven’t even heard of the basics we’ve grown up with, the way we eat at home. That’s where I figured there is something wrong in the narrative that we are promoting.

Q. What sort of education is required for all the stakeholders involved?

That’s what we’ll figure out together. This is my idea, but I alone can’t represent Indian food—all of us need to come together. When I spoke to chefs in India last October, they all agreed that we don’t understand Indian food. At Gaa, we’ve been able to create a modern tasting menu, but it’s completely based on Indian traditional techniques it’s not fusion, not deconstruction, it is trying to understand what Indian food can give us in terms of resources to make something new and different. We’ve been able to scratch the surface and understand a little bit, but there is so much more we need to get done.

The reason French cuisine is so popular with chefs around the world, or the reason it’s the basis of anything new, is that it’s catalogued and scientifically broken down. Auguste Escoffier sat down a century ago and jotted down these recipes, so if chefs today want their egg whites in a certain way, they would look for a French recipe to follow. In India we do everything andaaz se (through guesstimates). As much as that has gotten us to this point, we have to start cataloguing what we’ve mastered. But, then again, these are just my ideas and I have to listen to what everybody else is saying.  At Gaa, Garima Arora pairs unusual flavours, textures and techniques[br]Q. Could you give a few examples of the techniques you are talking about?

At Gaa, Garima Arora pairs unusual flavours, textures and techniques[br]Q. Could you give a few examples of the techniques you are talking about?

One of the things I am passionate about is negative food pairing. Let me explain this. Every ingredient you use in a recipe has a tasting note. Science has been able to identify 1,022 notes. In any given recipe of the West, or anywhere outside India, most of these ingredients will have a lot of flavour notes in common with each other. Only in Indian cuisine will the ratio be very low.

Dr Ganesh Bagler, a professor at IIIT-Delhi, is a physicist and a computational biology expert he has co-authored a paper on how Indian cuisine has the highest instances of such negative pairing. I came across the paper by chance and realised instinctively that is exactly what we do at Gaa. We pair the most unusual flavours, textures and techniques. Between caviar and strawberry, you have only one flavour note in common, but at Gaa, we bring it together for one of our most outstanding signature dishes through a technique that I derived from Indian cuisine—that even if two ingredients have just one common note, you can put them together by using fat as a medium.

These surprise people because it’s not instinctive to do it. But to us Indians, it comes so naturally. Bagler was the first to describe it in scientific terms. It’s one of the inspirations that sparked the idea. I don’t think there are too many Michelin-starred restaurants besides Gaa that serve a vegetarian main course as a tasting menu. The way we are able to draw out umami flavours from vegetarian food is something we should play to our advantage.

Q. How do you define modern Indian cuisine?

Indian cuisine is not limited to India. It’s in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore. It

spread across Asia with the Silk Route and with Buddhism. If we were to push the envelope and make a contribution to Indian cuisine, what would we do? For me, it needs to be a bit more of an intellectual exercise than what it has been in the past.

Q. Are we going to see an Indian outpost of Gaa anytime soon?

Absolutely not. Gaa will always remain in Bangkok. But that is not to say I will never do something in India. I will, and that is my eventual goal. India won’t see Gaa, but it will see Garima for sure.

First Published: Oct 05, 2019, 10:00

Subscribe Now