Koumarane Valavane: Bringing home the world

Theatre director Koumarane Valavane's journeys from Puducherry to France and back have enabled him to successfully experiment with the traditional and the contemporary

Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes IndiaPuducherry-based theatre maker Koumarane Valavane’s back-to-back competitive showings at Delhi’s Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META) over the last two years have placed him on the national map, somewhat belatedly. In April 2018, his Karuppu, a contemporary reimagining of ages-old Dravidian rituals, picked up awards for choreography, costumes and acting, while in August, his magnum opus Chandala: Impure premiered in Paris. This year, Chandala won two acting awards at META’s March ceremony.

Image: P Ravikumar for Forbes IndiaPuducherry-based theatre maker Koumarane Valavane’s back-to-back competitive showings at Delhi’s Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards (META) over the last two years have placed him on the national map, somewhat belatedly. In April 2018, his Karuppu, a contemporary reimagining of ages-old Dravidian rituals, picked up awards for choreography, costumes and acting, while in August, his magnum opus Chandala: Impure premiered in Paris. This year, Chandala won two acting awards at META’s March ceremony.

Although the accolades have piled up in recent years, Valavane’s troupe has, for more than a decade, quietly been at the forefront of theatrical experimentation in the country, infusing the traditional with the contemporary, while unobtrusively operating from a secluded vantage, and building a loyal audience base to help sustain a decidedly offbeat venture. The unassuming Valavane’s journey is full of serendipitous signposts, but underlining it is a doggedness that is the mark of a true artist.

Valavane’s interest in the performing arts wasn’t exactly sparked early. His grandfather, a policeman, had once been part of a therukoothu (Tamil traditional street theatre) troupe, but that was never talked about. “It wasn’t considered respectable, and dismissed as a ‘local village thing’,” remembers the 46-year-old. He grew up in coastal Karaikal, an erstwhile French territory, and the government school he attended as a child was a rare institution in which the medium of instruction was French. It was a creaking relic of Jawaharlal Nehru’s Francophilia, run by Indian teachers whose command over the language left much to be desired.

It did, however, engender within him an eagerness to experience France first-hand: “I was obsessed with the country. Everyone talked of Paris and the Eiffel Tower, and relatives brought back chocolates and trinkets.” Wary at first, his father finally relented to sending him abroad to study in 1987 for a 14-year-old it was like walking into a museum of treasures. But the dismal living conditions he endured in Sevran, a commune in a northeastern Parisian suburb, soon brought him down to earth.

Although he dabbled in theatre at school in Paris, it was only while he was a student of science at the University of the Mediterranean Aix-Marseille (in the south of France) that he formed a group, meeting at 7 pm on Tuesdays for rehearsals. In 1995, he helmed a compendium of short pieces, Huit Pièces (Eight Pieces), which debuted at an abandoned college building. Later, the fledgling outfit started touring villages around Marseille. Although his lack of formal training did little to stem Valavane’s enthusiasm as a director and actor, the impasse between his practice and knowledge led him to voraciously devour books on theatre, spending long hours in libraries.

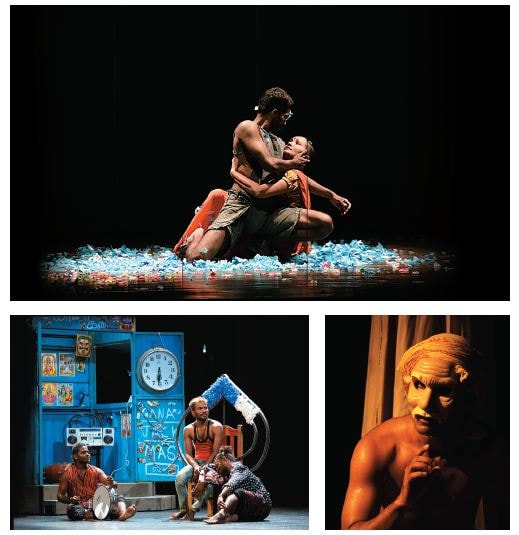

He clearly remembers one moment of truth from early 2001, when he encountered a photograph of an expressive flax-haired woman, faintly resembling Indira Gandhi, and holding a puppet. She was Ariane Mnouchkine, the legendary stage director. An emotionally charged Valavane felt propelled by an inexplicable force of compulsion to catch a flight that very day, and travel 800 km northwards to Vincennes in eastern Paris, where Mnouchkine ran her avant-garde company, Théâtre du Soleil, at La Cartoucherie, a former munitions factory. (Clockwise from top) Stills from Karuppu, Kunti Karna and Chandala: Impure

(Clockwise from top) Stills from Karuppu, Kunti Karna and Chandala: Impure

Courtesy: Indianostrum Theatre[br]“There were no buses from the local station in the evening, so I walked for long across the Bois de Vincennes, a park that was like a forest, till music fell on my ears,” he describes. The space was hosting a soirée celebrating the Tibetan New Year and, in a surreal turn of events, Valavane found himself partying with amiable strangers, in close proximity to Mnouchkine, whom he met formally the following day. There were no openings for actors, but when he mentioned his culinary skills, she took him on as assistant to the company chef.

The month-long apprenticeship firmed his resolve to return for a workshop in September that year, and this time Mnouchkine hand-picked him for an ensemble that would perform Le Dernier Caravansérail (The Last Caravanserai), a more than six-hour long spectacle that was pieced together from the stories of war refugees from across the modern world.

It was a difficult initiation into professional theatre. The reality of a working company, its pains and pleasures, its hierarchies and obligations, started to hit home. “I went through an interesting process with my ego. It was painful, but it resulted in something powerful, intense and beautiful,” Valavane reflects. Apart from Mnouchkine, he encountered another master—scenographer Erhard Stiefel. Assigned to assist him but forbidden from uttering a word, he observed Stiefel painstakingly sculpt masks out of wood, following little rituals and modest routines. “I discovered the unbelievable relationship between a man and his craft. It’s a very personal and individual matter. No one can understand my relation with theatre,” he says.

*****

Valavane carried these life lessons back with him to India. In 2007, with co-founders Vasanth Selvam and Cordis Paldano, he started Indianostrum Théâtre, the company that was to become his calling card. But disillusionment with their initial urban moorings set in early. “I realised that doing theatre in Chennai was a trap. There was much animosity within theatre circles, audiences were limited, and we knew nothing of the Tamil Nadu beyond,” he says. In 2010, Indianostrum toured from village to village with various Molière plays, which brought Valavane closer to both his Tamil cultural roots as well as his theatre origins in France.

In 2012, thanks to the largesse of a local church, Indianostrum set up shop in Puducherry in an old arthouse cinema, once known as the Salle Jeanne d’Arc. Catastrophically, a major fire gutted the building in 2013. However, community donations helped rebuild the space and it was here that Valavane’s métier as an offbeat theatre maker found its definitive expression with plays like Kunti Karna (2012), Karuppu (2014) and Chandala: Impure (2018), all featuring the elemental Selvam in the lead.

Valavane’s stint with Théâtre du Soleil had imbibed in him Western tools and imagery, which he realised he had to be weaned off. In fact, his early research had indicated the direction he was poised to take: European masters like Peter Brook, Mnouchkine, Jerzy Grotowski, Eugenio Barber or Vsevolod Meyerhold all spoke highly of Indian theatre techniques. For Kunti Karna, a corporeally delineated piece drawn from the eponymous poem by Rabindranath Tagore, and the French translation of the Mahabharata by Jean-Claude Carrière, the ancient martial art form of Kalaripayattu provided a distinctive physical grammar that Valavane stripped of its coded elements to create a fresh aesthetic that was still rooted. “I try to touch the core by removing all the decorations, and still evoke the essence of a traditional form. To this day, people ask me if Kunti Karna is part of traditional repertoire,” he says, triumphantly.

Similarly, while Karuppu uses visual motifs reminiscent of Mnouchkine’s oeuvre, it is a play that exists purely in the realm of the metaphorical. “I wanted to address the audience subliminally in Karuppu, just like religious rituals, which I consider to be the origin of theatre. In rituals, there is no narrative, but something talks to the person’s subconscious.” Set to a score by Jean-Jacques Lemêtre, the play is carried by the unbridled energy of performer Ruchi Raveendran.

Safely ensconced in their own space, Indianostrum kept whirring. In 2013, Valavane was invited to direct Dreams of Tipu Sultan for Ranga Shankara’s festival of plays by Girish Karnad in Bengaluru. Keeping the play’s radio origins in mind, rather than staging it, Valavane used a stodgy broadcast of the play as backdrop for a contemporary tale that unfolded in a police station. A ‘terrorist’ hanged on stage in the play’s climax was revealed as the playwright, even as fetid excreta trailed down his legs.

The premiere offended audiences to no small degree, and while organisers initially wanted the ending excised, they allowed a second show to proceed unexpurgated. But Valavane had to field questions in an irate session with viewers. “I had no issue with Karnad, as was being insinuated. The play is a political comment, only one person saw its connection to the execution of Afzal Guru,” he explains.

Meanwhile, the association with Mnouchkine continued. In 2016, an 80-strong contingent from Théâtre du Soleil arrived in India, with Valavane facilitating workshops with local practitioners and exploratory work for Mnouchkine’s Une Chambre en Inde (A Room in India), a play that made extensive use of elements of therukoothu and opened in Paris later that year. Reciprocally, Indianostrum travelled to Paris in 2017, and staged a limited repertoire of their plays at La Cartoucherie and other venues. This included One Third, part of the Land of Ashes trilogy of plays that Valavane has mounted on civil strife in Sri Lanka.

Accomplished Chandala: Impure, a caste-inflected take on Romeo and Juliet, pays equal homage to Tamil cinema and Shakespearean melodrama. It has been performed across India and in France. “This play allowed me to delve into my Indian side like none other,” says the director. How deeply ingrained caste is in the country’s social fabric startled him, and while the play offers no solutions, it doesn’t shy away from its theme’s complexities. “Almost everything reinforces caste in India, from economic forces to mythology. Even the most beautiful flowers are afflicted by the cancer of caste,” he observes.

Fourteen productions in a dozen years is indication enough of an enterprise’s robustness, but there have been struggles manifold to grapple with. The early years in Puducherry saw Valavane take to teaching in a school, his PhD in Theoretical Physics from Marseille finally coming in handy. Today, they are back in the driving seat, with local support and national recognition, while zealously guarding the experimental ethos they operate within. “I have always searched for my roots,” reiterates Valavane, and now it seems that he has come home at last.

First Published: May 18, 2019, 07:06

Subscribe Now