Travel: Vienna is reinventing itself

Vienna, judged the most liveable city in the world, is remoulding its historic identity with the help of technology and creativity

The city of Vienna, as seen from the observation deck of St Stephen’s Cathedral Image: ShutterstockThe early morning light glints off the spires of St Stephen’s Cathedral, as silence hangs in the air. In a few hours, it will be a vastly different scene, with the noise and bustle of hordes of descending tourists, matched by the swarms of vendors in kitschy Mozart costumes trying to sell concert tickets. But at this early hour, it is easier to appreciate not just the imposing cathedral but also some of the other magnificent structures in Vienna’s old town Innere Stadt, such as the Opera House and the Hofburg palace, and buildings in the MuseumsQuartier and those lining the Ringstrasse, a boulevard that circles the Innere Stadt.

The city of Vienna, as seen from the observation deck of St Stephen’s Cathedral Image: ShutterstockThe early morning light glints off the spires of St Stephen’s Cathedral, as silence hangs in the air. In a few hours, it will be a vastly different scene, with the noise and bustle of hordes of descending tourists, matched by the swarms of vendors in kitschy Mozart costumes trying to sell concert tickets. But at this early hour, it is easier to appreciate not just the imposing cathedral but also some of the other magnificent structures in Vienna’s old town Innere Stadt, such as the Opera House and the Hofburg palace, and buildings in the MuseumsQuartier and those lining the Ringstrasse, a boulevard that circles the Innere Stadt.

This historic centre of Vienna, with its mix of Medieval and Baroque architecture, gives the city its main identity. But in the last decade or so, it has incorporated within the folds of this old-world image elements of a sleeker and more modern way of life that combines technology with creativity.

In 2019, The Economist magazine named Vienna as the most liveable city in the world for the second year in a row based on an annual survey by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU). The survey ranks 140 global cities based on 30 factors grouped into five categories such as environment, infrastructure, health care, stability and culture. Vienna scored an enviable, near-perfect score of 99.1 out of 100. EIU’s ranking followed the Mercer Quality of Living Survey, which has ranked Vienna at the top for 10 years in a row.

Even in the midst of buildings that go back centuries, it is not difficult to see why the city scores aces on these parameters. Travelling is relatively easy, thanks to the extensive public transport system of underground buses, trams and subway trains. And then there are environmental friendly Viennese inventions such as the Vello, a compact and lightweight electric bicycle that is foldable as well as self-charging. Made by award winning-designer Valentin Vodev, it looks delicate and flimsy but is surprisingly sturdy. Streets too are designed to accommodate cyclists. Vienna University of Economics & Business Image: ShutterstockCrossing the city this bicycle through the Prater Hauptallee boulevard, past the modern buildings of the Vienna University of Economics and Business and heading towards the Innere Stadt, I could see the different architectural styles of the buildings reflect Vienna’s history as well as its incredible resilience. For instance, the trendy Praterstrasse, an avenue leading into the city centre, was ransacked by the troops of French Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte in 1809, but bounced back in less than a decade to become the playground of the rich and famous. It was somewhere on this street that Austrian music composer Johann Strauss II created his most famous piece ‘The Blue Danube’ in 1866.

Vienna University of Economics & Business Image: ShutterstockCrossing the city this bicycle through the Prater Hauptallee boulevard, past the modern buildings of the Vienna University of Economics and Business and heading towards the Innere Stadt, I could see the different architectural styles of the buildings reflect Vienna’s history as well as its incredible resilience. For instance, the trendy Praterstrasse, an avenue leading into the city centre, was ransacked by the troops of French Emperor Napoléon Bonaparte in 1809, but bounced back in less than a decade to become the playground of the rich and famous. It was somewhere on this street that Austrian music composer Johann Strauss II created his most famous piece ‘The Blue Danube’ in 1866.

Today, the street houses fashionable cafes and avant garde establishments such as the Supersense Shop, with its collection of all things analogue that are meant to tease, engage and satiate the senses. At once modern and retro, it is located inside a former Viennese palace and houses a virtual feast for the five senses, and encourages visitors to take a step back from everything digital. On display are devices such as film cameras and music turntables, a large collection of vials with various smells, alongside a recording and photo studio.

Back on the cycle, as I head towards the old city, the skyline gets noticeably older and grander, until I reach the Mariahilferstrasse. A wide street flanked by trees, it is Vienna’s most popular shopping street, filled with boutiques and international brands. Although it was completely pedestrianised in 2015 in an effort to increase car-free areas in the city, bicycles are welcome and I am suddenly in the company of scores of others cyclists. Mariahilferstrasse, Vienna’s most popular shopping street Image: ShutterstockVienna’s love for the environment-friendly bicycle is perhaps reflected best in the family-run Hotel Am Brillantengrund, with its little nondescript arched entrance, and a separate room for all things associated with cycling, including cool aids, gear and clothes. A favourite haunt of cyclists, it is not unusual to find them here, hotly debating the best possible cycling routes around the city.

Mariahilferstrasse, Vienna’s most popular shopping street Image: ShutterstockVienna’s love for the environment-friendly bicycle is perhaps reflected best in the family-run Hotel Am Brillantengrund, with its little nondescript arched entrance, and a separate room for all things associated with cycling, including cool aids, gear and clothes. A favourite haunt of cyclists, it is not unusual to find them here, hotly debating the best possible cycling routes around the city.

Vienna’s eco-friendly credentials are also illustrated by HoHo Wien, a housing project coming up on the Western periphery of the city, on the banks of the Asperner See. Conceptualised as a green building complex, it comprises a 24-storey high rise built of timber that has been sourced sustainably from Austrian forests.

But perhaps no other aspect of Vienna has had as much influence on its quality of life as its culture. Home to classical composers such as Strauss and Franz Schubert, and associated closely with Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and German composer Ludwig van Beethoven, the city flourished as a hub of music and art in the 19th century. A profusion of music and concert halls around the city also adds to Vienna’s identity as a city of music.

In contemporary times, musicians such as Conchita Wurst, a pop singer and drag queen, have been instrumental in maintaining this identity by winning Eurovision 2014 and collaborating with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, thus blurring the lines between the traditional and modern. The city is now readying to celebrate 2020 as the year of music to mark Beethoven’s 250th birth anniversary.

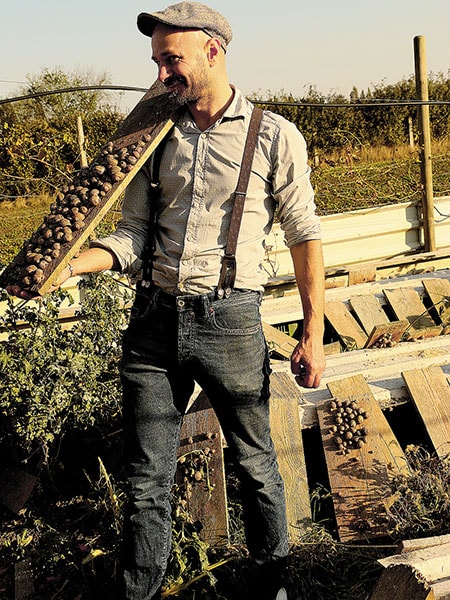

As with music, there are inroads being made into the city’s conventional culinary scene by a subtle wave of Neue Wiener Kuche or new Viennese cuisine. For instance, in the Southern part of the Favoriten district, Viennese resident Andreas Gugumuck runs a snail farm. A Viennese staple, the gastropods had inexplicably disappeared from the menus about three decades ago, and Gugumuck has helped reintroduce them by starting the farm in 2014. “It’s a slow business,” he deadpans. Many restaurants, however, have become regular customers and host a ‘snail week’. Gugumuck also offers a seven-course menu in his bistro once a week, with snails as the main attraction. A snail farm run by Viennese resident Andreas Gugumuck. He helped reintroduce gastropods in restaurant menus and homes Image: Anita Rao KashiAdding a similar contemporary touch to culinary traditions is the Gegenbauer Vinegar Brewery in the Waldgasse neighbourhood, which stands engulfed in a cloud of vinegary vapours. Established in 1929, it started as a maker of pickled vegetables but now produces some 70 kinds of vinegar made from vegetables, fruits and even coffee. Underneath the store is a vinegar cave—a fascinating place where all kinds of vinegars are ‘curing’ in bulbous glass vats.

A snail farm run by Viennese resident Andreas Gugumuck. He helped reintroduce gastropods in restaurant menus and homes Image: Anita Rao KashiAdding a similar contemporary touch to culinary traditions is the Gegenbauer Vinegar Brewery in the Waldgasse neighbourhood, which stands engulfed in a cloud of vinegary vapours. Established in 1929, it started as a maker of pickled vegetables but now produces some 70 kinds of vinegar made from vegetables, fruits and even coffee. Underneath the store is a vinegar cave—a fascinating place where all kinds of vinegars are ‘curing’ in bulbous glass vats.

Keeping an old culinary tradition alive is Weingut Christ, in the Jedlersdorf district, one of the handful of wineries that continue to operate within city limits. Perhaps the only capital in the world with vineyards and wineries within the city, the Viennese wine tradition goes back several centuries. In the 18th century, the Hapsburg rulers granted wine makers the licence to sell their produce on their premises, giving rise to heurigers or wine taverns.

The heuriger tradition is not just about wine and food, but the air of genial conviviality, the sharing of meals with family and friends, and lively music. There’s even a word for it—gemütlichkeit. But while the entrance to Weingut Christ is old-world—aged wooden tables stand covered in table cloths and laden with vases overflowing with flowers—beyond the tavern is the winery with giant steel tanks, processing units and a massive loading area.

Back in the city centre, the setting sun turns the waters of the Danube into a gently flowing strip of gold. And against the darkening sky stands the timeless spires of St Stephen’s Cathedral, while around it, the city slowly breathes new life into its centuries-old existence.

First Published: Feb 22, 2020, 08:26

Subscribe Now