What drives managers to sabotage talented employees

Intense competition in the workplace may lead managers to sabotage talented employees to protect their own job security, says research by Hashim Zaman and Karim Lakhani

In competitive workplaces where colleagues are evaluated relative to each other, peers may resort to sabotage in a quest for more compensation or promotions. Recent research finds that the intensity of competition can be strong enough that even supervisors may undermine talented subordinates to prevent future competition and enhance personal job security.

This top-down sabotage, in which managers deliberately forestall the career progression of subordinates, is surprisingly common. The vast majority of corporate executives say they have witnessed it in their careers—and many openly admit to sabotaging their employees, according to a survey-based study conducted by Hashim Zaman, a postdoctoral fellow at the Laboratory for Innovation Sciences at Harvard, and Karim Lakhani, the Dorothy and Michael Hintze Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School.

Why do executives sabotage more junior staff? Managers often view their high-performing subordinates as threats to their position and power, Zaman says.

"Typically, sabotage is directed toward more capable colleagues," Zaman says, "In a hierarchical organization, your manager may see you as a future peer, a competitor for further promotions, or even a replacement risk, so they have an incentive to use their authority to mitigate your growth ahead of time."

This pre-emptive undermining not only limits the careers of talented employees, but can hurt organizational culture and damage corporate performance, Zaman says. Plus, he says, with the relatively low unemployment rate forcing companies to compete for talent, an organization known for top-down sabotage could struggle to hire and retain employees, thereby jeopardizing succession planning.

"The manager is supposed to act in the best interests of the firm, but personal interests can take precedence," Zaman says.

The solution, his research shows, is to conduct more transparent performance evaluations and foster a culture of trust within organizations, where employees have a sense of belonging to the organization and can comfortably talk to their colleagues rather than work in silos. Organizations need to work on incentives and control systems, particularly corporate culture, so managers are motivated to focus less on jockeying for power and more on the organization"s needs.

Zaman surveyed 335 executives for his recent working paper, "Determinants of Top-Down Sabotage," cowritten with Lakhani. The researchers found:

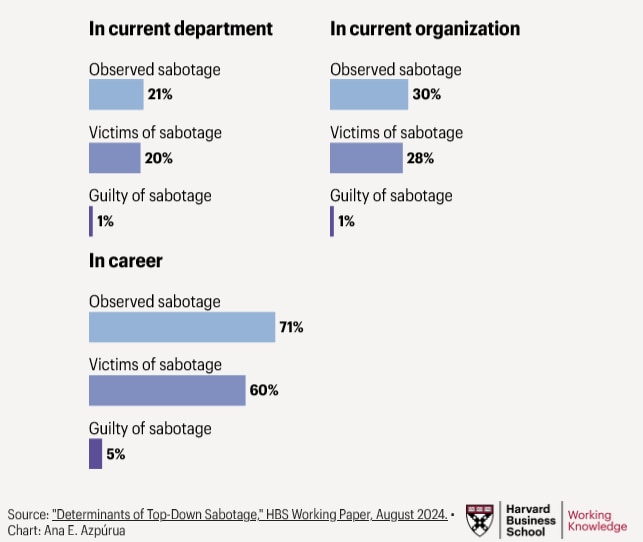

About 30 percent observed sabotage in their organizations, and 71 percent witnessed top-down sabotage at some point during their careers. In fact, 5 percent even admitted to sabotaging their direct reports over the course of their careers.

About 28 percent of respondents reported being victims of top-down sabotage in their organizations, and 60 percent were impacted by it during their careers.

Only about 3 percent of respondents said managers sabotaged employees based on money concerns alone. In contrast, about 21 percent said status concerns alone led to sabotage, and 24 percent said both status and money concerns drove managers to sabotage employees.

An online survey of 335 corporate executives revealed that most had, at some point in their careers, observed managers undermining their subordinates.

Zaman and Lakhani also explored whether top-down sabotage was more common among businesses that use relative performance evaluations, which rely on comparing the performance of employees against one another for compensation and promotion decisions. This approach is popular because it provides a simple way to assess employees" skills and increase productivity with less employee tracking, Zaman says.

"The upside of relative performance evaluations (RPEs) is that you don"t need to monitor employees as closely because they are already engaging in efforts to outperform each other," he says.

In studying organizations that use RPEs, the researchers found that top-down sabotage is slightly more prevalent. About 38 percent of organizations that benchmark employees against one another saw top-down sabotage, compared with 33 percent of organizations that don"t use the approach.

When managers have more subjective discretion in the evaluation process, top-down sabotage increases. Within RPE-based organizations, when the researchers broke out firms that gave managers more influence in identifying outperformers and those worthy of promotions, top-down sabotage climbed to 47 percent. On the other hand, firms without subjective managerial discretion over RPE showed a noticeable decrease in sabotage to 27 percent. "It"s not just relative performance evaluations themselves," Zaman says. "The discretion managers have over the RPE process defeats the purpose of implementing RPE in the first place. If employees begin to anticipate top-down sabotage, they may not be motivated to exert the effort that a firm would expect under RPE."

To explore what prompted people to undermine one another, Zaman conducted a separate study and asked participants to evaluate social media posts written by several people and select one to partner with on writing additional social content. He found:

When paid based on absolute rather than relative performance, participants chose the more talented partner. When the participants were told that they would be paid for the quality of the work they produced regardless of the partner they choose, 90 percent of participants chose the person who wrote the better posts.

When pay was based on relative performance, participants chose the more talented poster less often. In this case, only 60 percent chose the person who wrote the better posts.

"People were openly admitting, "Yeah, I deliberately sabotaged because I wanted to avoid competition."" Not only that, says Zaman, "but when it came time to write their own posts, they stole the posts of the person they had not selected, passing them off as their own."

The question is how to prevent such managerial rent-seeking while retaining the motivation and monitoring benefits of RPE, he says.

Following that experiment, Zaman constructed a theoretical model to probe top-down sabotage further along with V.G. Narayanan, the Thomas D. Casserly, Jr. Professor of Business Administration at HBS. Zaman also wrote an analytical paper with Peiran Xiao, an economist at Boston University, to explore how organizations can manage employee selection and succession planning when sabotage is a concern. They propose that giving managers an organizational head start to insulate them from potential competition could mitigate sabotage.

"If you maintain that hierarchy without compromising on meritocracy, so the manager is less concerned about being immediately outperformed by someone they hire, it can lead to better hiring decisions," says Zaman, who continues to explore different management control systems to improve succession planning outcomes for organizations.

In exploring the connection between organizational culture and sabotage, Zaman and Lakhani"s research revealed that companies that encouraged open communication, collaboration, and transparency were least likely to experience the phenomenon.

"When employees feel they work at an organization where there"s a sense of belonging, it substantially reduces the problem," Zaman says. To strengthen the culture and reduce the incidence of top-down sabotage, Zaman recommends that organizations:

Ensure that the performance evaluation process is clear and visible and that employees receive credit for their work. This will reduce opportunities for managers to claim credit for subordinates" work and help employees feel their efforts are valued and rewarded.

Introduce transparent, objective, standardized criteria for performance evaluations to minimize manager influence in decisions about promotions and compensation.

The mere existence of a 360-degree feedback system-where employees are evaluated by those above, beneath, and next to them- doesn"t ensure fairness, since employees may not respond honestly for fear of backlash or retaliation. Research finds that merely implementing 360-degree feedback system without effective enforcement exacerbates the problem of top-down sabotage in organizations.

Employees need to develop a sense of belonging to the organization. An organizational culture where employees can comfortably talk to their colleagues, speak their minds, and trust that their efforts will be recognized can substantially reduce top-down sabotage and improve succession planning efforts. With that in mind, organizations should encourage open communication and collaboration across teams. Employees should feel comfortable sharing ideas and asking questions without fear of being undermined.

Shift incentives from individual performance to team-based success, rewarding managers and employees for their teams" overall performance. This can reduce competition and fear of being replaced. It"s also important to remember that incentivizing a manager for growth of the entire team does not preclude the manager from sabotaging a talented subordinate, Zaman notes. Team-based incentives are only effective if they are optimized for transparent performance evaluation of every individual on the team.

"The single biggest tool to fix succession planning and mitigate the problem of top-down sabotage is to improve organizational culture," Zaman says.

First Published: Jan 28, 2025, 12:19

Subscribe Now