India's ultra-rich and philanthropy: Someone's gotta give

Philanthropy in India is a half-written story. The super-rich need to push the envelope of giving in the social sector

Wipro founder Azim Premji (left) and HCL Founder Shiv Nadar are two of the most prominent philnthropists from India Inc

Wipro founder Azim Premji (left) and HCL Founder Shiv Nadar are two of the most prominent philnthropists from India Inc

Nadar Image: Amit VermaIt was a simple exercise of joining the dots. Two unrelated ranking lists, released just a few days from each other, revealed a common thread.

First, the 2019 Forbes India Rich List showed that 14 of its 100 listees became poorer by $1 billion or more, and the total wealth of billionaires in the country shrank by 8 percent from last year’s $452 billion. More than a third of this decrease was ascribed to Wipro Founder Azim Premji, and his philanthropic endowment worth $21 billion, which brought his ranking down from No 2 last year to No 17 this year.

While the dip in fortunes of most other listees was a result of slowing demand, domestic and global market conditions, for two more billionaires—HCL Founder Shiv Nadar and Infosys Co-founder Nandan Nilekani—it could be attributed specifically to their philanthropic efforts. While Nadar’s net worth saw a marginal erosion from $14.6 billion to $14.4 billion, Nilekani is the only Infosys co-founder (among NR Narayana Murthy, SD Shibulal, K Dinesh and Kris Gopalakrishnan) with a reduced net worth—from $1.96 billion last year to $1.81 billion in 2019.

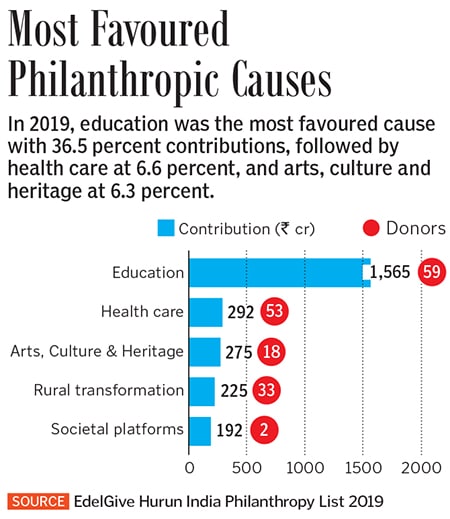

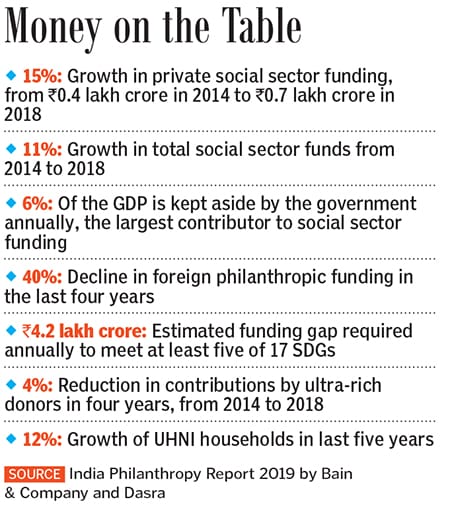

Now the second list. Nadar, Nilekani and Premji found themselves at the forefront of the EdelGive Hurun India Philanthropy List 2019, a ranking of the country"s top 100 philanthropists. While Nadar topped the list with contributions of $0.124 billion (₹826 crore) last year, he was followed by Premji (₹453 crore or $68 million) and Nilekani (₹204 crore or $30.66 million). The cumulative amount of philanthropic contributions of people on the list was ₹4,391 crore this year, up from ₹2,310 crore in 2018. (This report does not consider the 39 percent of Wipro shares that Premji transferred to his Foundation in 2015.)While the list shows how some of India’s richest are walking the talk by focusing on philanthropy to the extent that it erodes their personal wealth, it also revealed a staggering gap: Ten individuals made 61 percent of the total contributions last year, while the other 90 accounted for just 39 percent.This point had been driven home earlier too. The India Philanthropy Report 2019, released in March, indicated that ultra-high net worth individuals (UHNIs), or those with a net worth of more than $50 million, were actually giving less than they did five years ago. The report, published by management consultancy Bain & Company and non-profit organisation Dasra, indicated that individual contributions to philanthropy amounted to ₹43,000 crore, out of which 55 percent was by UHNIs who individually donated more than ₹10 crore. However, Premji alone contributed more than 80 percent of this, while total UHNI contributions dropped by 4 percent since 2014.

India needs an additional ₹4.2 lakh crore (about $60 billion) annually to achieve at least five of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) that member countries of the United Nations General Assembly have promised to achieve by 2030. India’s UHNIs need to do at least 2.5x to 3.5x more philanthropy than what they are doing now to fulfil the country’s 20 percent contribution to global SDGs.

“We’re still stuck with a lot of funds going into legacy giving—where philanthropists run schools or hospitals in the name of their forefathers—as opposed to thinking about systemic change and what one must do at a national level to move the needle on critical issues,” says Deval Sanghvi, partner and co-founder, Dasra, who believes that the time taken to change mindsets from giving to remember family legacy to giving for problem-solving is too long.

Collaboration and Regulation

Philanthropists are quick to claim that they are gradually redefining the culture of giving: Five Indians, including Premji, Biocon Chairman Kiran Mazumdar-Shaw, Rohini and Nandan Nilekani, and real estate tycoon PNC Menon are signatories to The Giving Pledge launched by Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett meaning they have promised to give at least half their wealth to philanthropy. Billionaires have also, over the years, adopted fresh approaches to humanitarianism: From using technology to find solutions for development issues, to moving away from ‘chequebook charity’ towards more ground-level work with social organisations.

“No matter how much we do, it will never be enough. There will always be more work to be done and more problems to solve. So we just have to focus on making a difference with whatever we have,” says Sangita Jindal, chairperson of the JSW Foundation. She believes that with increasing economic disparity between the "haves" and "have nots", government officials struggle with lack of resources and do not plan projects properly. It is therefore important, she says, for individual givers to join hands with the government, non-profits, and with each other. [qt]There will always be more work to be done and more problems to solve. So we just have to focus on making a difference with whatever we have.

[qt]There will always be more work to be done and more problems to solve. So we just have to focus on making a difference with whatever we have.

Sangita Jindal, chairperson, JSW Foundation

Image: Aditi Tailang[/qt]“There is no ego in philanthropy and CSR. We work with the Hindujas, Tata Trusts and others on various projects to collaboratively create an impact,” she says. Jindal, who has given ₹21 crore last year (according to the Hurun India Philanthropy list), works predominantly in the areas of art and heritage preservation, women empowerment, and livelihoods.

Second, taxation laws for the social sector are complex. “India should utilise philanthropic capital to build leapfrogging opportunities in health, education and environmental sustainability, [but] the situation today seems to be one of government abdication of philanthropy that will simply waste good philanthropic resources,” says Mazumdar-Shaw.

Rohini Nilekani, the founder-chairperson of water and sanitation foundation Arghyam, feels that the government needs to rethink rules regulating the social sector. For example, she explains, NGOs often live in fear of losing their 12A or 80G registrations [for tax exemption] when they have not spent 85 percent of their funds annually, as mandated by law. “Even if it means paying tax on extra income, a non-profit should be able to continue operating as a non-profit,” she says. “It is not easy for non-profits to balance financial stability, organisational structures and taxation requirements. I think there is scope to change that a bit.”

Charity-friendly policies, like in the US and UK, would further encourage philanthropists who have the intent to give back, say asset managers. The Estate Tax in the US for example, an analyst explains, helps inheritors save half their wealth from being taken away as taxes, if they invest in government-approved charity. “India does not have this, and people here usually do not write big cheques during their lifetimes... or they write them if they are running their own organisation,” says the analyst, who did not want to be identified.

According to the India Philanthropy Report 2019, the number of ultra-high net worth households in India have grown at 12 percent over the last five years and is likely to double in both volume and wealth: From 160,600 households with a combined net worth of ₹153,000 crore in 2017 to 330,400 households with a combined net worth of ₹352,000 crore in 2022.

“Around 80 percent UHNIs feel philanthropy is important to them and about three-fourth have included philanthropy in their annual expenditure plan,” says Gautami Gavankar, executive director-trusteeship services, Kotak Mahindra Trusteeship Services, quoting from the Kotak Top of the Pyramid Report, 2017. “That said, UHNIs often have questions around giving, such as the type of causes to support, access to relevant information, whether the social organisations they support have the capacity or longevity to fulfill their commitment, and the long-term impact of solving social issues." Keeping this in mind, she explains, some families prefer to form their own foundations while others contribute only to professionally-run nonprofits with a credible track record. [qt]The situation today seems to be one of government abdication of philanthropy that will simply waste good philanthropic resources.

[qt]The situation today seems to be one of government abdication of philanthropy that will simply waste good philanthropic resources.

Kiran mazumdar-shaw, chairperson & managing director, Biocon[/qt]Nilekani—who dedicated ₹142 crore to philanthropy last financial year [as per the Hurun India Philanthropy list]—believes that philanthropists themselves have a huge responsibility in helping NGOs build capacity and scale. “Most social organisations in India need unrestricted support, freedom and trust from philanthropists to be able to scale and learn what works.” She also insists on looking at scale differently: Rather than investing huge amounts in one organisation to scale up, it is prudent to invest in multiple platforms or initiatives working toward the same cause.

Anurag Behar, CEO of the Azim Premji Foundation, which is one of the world’s largest philanthropic initiatives backed by a $21 billion contribution from Premji, believes that the previous generation of businessmen like JRD Tata, Jamnalal Bajaj and Ambalal Sarabhai had more wisdom and humility to understand complex social realities, as compared to "many of the—even sincere—philanthropists of today".

He says: “In the social sector, unlike business, you cannot have perfect solutions, just efforts toward improvements,” he says. “Not always, but too often, people who have money start believing that they have all the solutions and that they know better.”

The Road Ahead

The average age of UHNIs in India is falling: About 60 percent of them were under the age of 40 in 2018, up from 47 percent the previous year, as per the 2018 Kotak Wealth Management Report. And they are looking at philanthropy differently too. As Mazumdar-Shaw puts it: “While every generation aligns to the theme of ‘giving back to society", yesterday’s philanthropists equated it with charity, while today’s philanthropists seek impact through social inclusiveness.”

Kairav Engineer, son of billionaire Sandeep Engineer of Ahmedabad-based Astral Pipes, explains that while his father focussed on health care initiatives like charitable hospitals, he is passionate about water and forest conservation.

He has undertaken projects to secure tribal livelihoods and resources in the Ranthambore and Sariska National Parks in Rajasthan, and Nagarhole in Karnataka. “While access to education and health care, are crucial, young philanthropists should also consider working around threats like climate change and water scarcity, which are here today and likely to create much disruption soon.” [qt]It is not easy for non-profits to balance financial stability, organisational structures and taxation requirements. there is scope to change that a bit.

[qt]It is not easy for non-profits to balance financial stability, organisational structures and taxation requirements. there is scope to change that a bit.

Rohini Nilekani, founder-chairperson, Arghyam

Image: Forbes India[/qt]Hari Menon, country director for India, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, says that while a lot of entrepreneurial wealth is generated in India, individual net-worths calculated through valuations might not be a definitive indication of actual wealth. That said, he believes that novel giving philosophies adopted by India"s new generation of leaders—who, according to him, "demonstrate an increased awareness of the social responsibility of wealth holders"—can improve the overall quality of giving in India.

“Government and civil society must prepare a vision for the philanthropic sector. Transparency about regulations and compliance is important to help people make longer-term bets,” Menon says.

Entrepreneurs like Nikhil Kamath, co-founder of Zerodha, have already realised the importance of creating a strong network connecting leading philanthropic families with younger benefactors. In October he launched True Beacon, a company that will invest in Indian capital markets for UHNIs. The organisation, he says, will have a strong philanthropy component. “We want to bring strategic investors from some of the most notable families, and create a platform that will help them collaborate and take up philanthropic initiatives,” says Kamath, who is going beyond Zerodha’s grant-making CSR strategy to do individual philanthropy in the areas of contraception and water scarcity around his city, Bengaluru.

Helping Kamath is Zerodha’s senior advisor Richard Pattle, who, previously as vice chairman of Standard Chartered Private Bank in London, specialised in global philanthropy. He says that being cognisant of the power of partnerships will help the next generation strengthen the culture of philanthropy in the country. “The younger generation of philanthropists, led by people like HCL’s Roshni Nadar, takes risks, deploys capital in new initiatives, engages closely with national or global NGOs to scale, and even leads governments in social sector projects,” he says.

Menon predicts that India’s philanthropic sector is evolving, and things will only get better. “There are green shoots that need to be nurtured. So, for now, we just need to keep the conversation going.”

First Published: Nov 30, 2019, 08:28

Subscribe Now