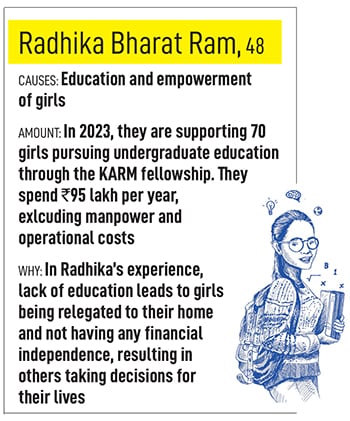

So, when Radhika Bharat Ram says she cannot see complete change in her lifetime even when she works in her capacity to help poor girls pursue higher education and build careers, it feels like a statement rooted in reality. “How do you even measure these things?" asks Radhika, daughter-in-law of Arun Bharat Ram, the billionaire promoter of specialty chemicals and packaging firm SRF. “Philanthropy requires patience. You are dealing with human beings, not machines."

That said, she hopes her efforts will help create a ripple effect that not only helps young girls be financially independent and socially empowered, but also become role models who can “transform their family and community for generations to come".

It was in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 that Radhika, along with husband Kartik Bharat Ram (deputy managing director of SRF), founded the non-profit KARM Trust that runs a fellowship for girls wanting to pursue undergraduate education at Delhi University. The scope of the three-year fellowship covers fees (academic and exams), local travel allowance, laptops and internet dongles, books, accommodation for outstation students, apart from access to mentors, internships, career counselling, and self-improvement workshops. Vinita Johorey, a trained counsellor who has worked with organisations like the Concern India Foundation and the KC Mahindra Education Trust, is the head of the fellowship.

Radhika, who is joint vice chairperson of The Shri Ram Schools in Delhi that is run by the SRF family, has tapped into her rich network of people in business and the social sector to make sure one personal mentor is assigned to every girl. These mentors help them with navigating career choices, internships and job opportunities. Mentors at the KARM fellowship include Tara Singh Vachani, executive chairman of Antara Senior Living and vice chairman of Max India Limited Rumjhum Chatterjee, co-founder of Feedback Infra Group Aditya Ghosh, co-founder of Akasa Air Anu Prasad, founder and CEO of India Leaders for Social Sector.

The foundation received close to 500 applications for their first cohort in 2021, of which Radhika, Kartik and team shortlisted 77 girls, and finally had a batch of 20. In 2022, it was 24, and in 2023, 26 students. “I read the application sent in by every girl, which is about 1,800 in total as of this year," says Radhika. “By July, we will have 70 girls across three cohorts this year and I know every girl by name."

They spend about ₹95 lakh annually for the fellowship, apart from manpower expenses for running the fellowship, which Radhika and Kartik fund from their personal wealth. They also receive support from other individuals, corporations and foundations in their network.

The All India Survey of Higher Education for 2019-20 (the latest available) gives the gross enrolment ratio in higher education for girls aged between 18 and 23 in India using population projections based on the 2011 Census. About 27.9 percent of girls are enrolled in higher education institutions the number is 23.9 percent for girls belonging to the Scheduled Caste and 19.1 percent for girls from the Scheduled Tribes.

A lot of young girls are clearly not pursuing higher education, and given the extent of the problem, Radhika felt the guilt of leaving many other girls behind, says Amitav Virmani, founder and CEO of non-profit The Education Alliance, and one of the first people with whom Radhika discussed her idea for the fellowship. “So initially, we thought of launching a pure-play scholarship so we can reach more girls," he says.

![]() But slowly, they decided that merely funding education expenses for three years is not enough if the girls are not prepared with the skills, confidence and exposure to take that education forward. This resulted in them formalising the idea of the fellowship, where they have taken on fewer girls, but have “encompassing provisions", Virmani says, to ensure their knowledge translates to improved confidence, and helps them build a successful career.

But slowly, they decided that merely funding education expenses for three years is not enough if the girls are not prepared with the skills, confidence and exposure to take that education forward. This resulted in them formalising the idea of the fellowship, where they have taken on fewer girls, but have “encompassing provisions", Virmani says, to ensure their knowledge translates to improved confidence, and helps them build a successful career.

“Philanthropy is not just about giving resources, it’s about giving time," says Radhika, 48. “It’s about working with people, understanding them and co-creating solutions with them instead of for them."

She wants to make sure that when she is talking about touching the life of “every individual girl", she is able to do justice by giving personal time and attention to every student. “Everything doesn’t need to be big. Whatever we are going to do, we will do it well."

Naghma Mulla, CEO of EdelGive Foundation, who has not collaborated with Radhika but is aware of her philanthropic efforts, calls it “ahead of its time".

Education is the most-preferred cause among philanthropists. As per the EdelGive-Hurun India Philanthropy List 2022, education received ₹1,270 crore from 76 donors, which is 20.2 percent of the total philanthropic contributions in India.

According to Mulla, not many philanthropic efforts focus specifically on higher education, which is important, because students continue to drop out of school and not pursue higher education. At this stage, while boys are encouraged to pursue jobs and earn money, girls are often relegated to the household with domestic and caregiving responsibilities. This happens for various reasons, from social prejudices to parents not being able to—or not wanting to—afford education for their daughters.

“Once they finish schooling, are there incentives that get girls to higher educational institutions? Once they get there, can these degrees lead them to job opportunities? And are social norms supportive of this?" Mulla says, adding that philanthropy can help bridge these gaps.

“Student learning outcomes are not just a result of great teaching or children being in classrooms, but also their ability to get to that place. Philanthropy can come in there, beyond just funding institutions, but supporting students to access these institutions and absorb learning," explains Mulla. “That’s why I find Radhika’s initiative to be much ahead of its time. Not a lot of people do this."

Shabana Ansari is an example of the point Mulla is trying to make. Her parents moved from their village in Bihar to Delhi in search of a better life. Her father is a wage labourer and her mother is a homemaker. Shabana, 21, lives in a shanty and is the oldest sibling with three brothers. She is pursuing second-year BCom (Honours) from Deshbandhu College. “Sometimes I think, if she [Radhika] had not started this fellowship, what would have become of me?" she says.

When she finished schooling, Shabana’s father discouraged her from studying further, saying he could not afford the expenses. “What I should do with my life was determined by what my parents, relatives and what the society wants," she says. “But I decided to apply for this fellowship so that I can earn money, which will help me live life on my own terms."

Just getting these girls into school is not enough, Virmani points out. For example, he says, almost all the girls in the first cohort of the KARM fellowship wanted to pursue UPSC examinations or take up a government job, because “they have heard from their family and relatives and community that a sarkari naukri [government job] is the most secure". They do not have any exposure about various other career opportunities, and are often scared and confused, which is why mentorship is extremely important, he explains.

Ansari, for example, went from wanting to be a lawyer, to a public relations (PR) professional, to now wanting to pursue a career in the social sector. She has taken the first step with an internship with Teach for India.

‘Jhansi ki Rani’

Radhika had a “middle-class" upbringing in which philanthropy meant volunteering in non-profits like the Cheshire Home and the Mother Teresa Home. She got her BCom degree from Delhi University and then got married into an industrial family, where, with guidance from her mother-in-law, Manju Bharat Ram, she started volunteering at the Delhi Crafts Council. This was 15 years ago. She worked with the craftspeople for their rights and empowerment. “We worked together to find solutions that worked for them, rather than me prescribing something to them and telling them it’ll work."

Then, about four years later, she became the joint secretary of the Blind Relief Association, another milestone in her philanthropic journey. “During my work in both these places, I didn’t see many women. I was also the chairperson of the Indian Blind Sports Association and it was a struggle to find female athletes to support," she says. Even at Delhi Crafts Council, money for work done by female artisans was typically transferred to the bank accounts of their husbands.

![]()

These experiences, Radhika says, shaped the making of KARM, and her desire to help girls assert their independence and take control of their lives from a young age. But here too, she does not want to be prescriptive in her approach. “What I learnt from my mother-in-law is that as a philanthropist, it’s more important that I provide agency to people to solve their problems," she says. “My parents raised my sister and me like we were Jhansi ki Rani, to be fearless, take risks and never shy away from voicing our opinion. I want each of my girls to do the same."

She has the word ‘KARM’ tattooed on her forearm, and says it’s an acronym for [Kartik-Ahaana Radhika-Maahir], her husband, daughter and son. While her son launched an initiative within KARM to use gender disaggregated data to help understand problems faced by women, Radhika’s daughter leads a programme to create awareness about menstrual hygiene and menopause.

KARM fellows say that Radhika is accessible and helpful. “She is there for every workshop, every event and session that is organised for fellows. We can contact her anytime. She is always pushing us to get out of our comfort zone," says Teena Sahu, who is pursuing second-year BSc Computer Science. Ansari adds that before she met Radhika, she thought the rich lead different lives and can never be on the same page as someone in her social situation. “But she [Radhika] is a pillar of support for each one of us."

Virmani believes Radhika is a good philanthropist because she knows she does not have all the answers and wants to learn. “She is willing to speak with people, sector experts, and is building a quality team with good people who can work together to take the cause forward."

He says that while the shortlisting criteria for KARM fellows is largely around picking the brightest of the lot, going forward he hopes that the fellowship will grow to an extent where they are also able to support girls who might be average but cannot make it in life without support offered by a fellowship like this. “I hope we get to a place where we can bring out the true value of even the average girl child."

But slowly, they decided that merely funding education expenses for three years is not enough if the girls are not prepared with the skills, confidence and exposure to take that education forward. This resulted in them formalising the idea of the fellowship, where they have taken on fewer girls, but have “encompassing provisions", Virmani says, to ensure their knowledge translates to improved confidence, and helps them build a successful career.

But slowly, they decided that merely funding education expenses for three years is not enough if the girls are not prepared with the skills, confidence and exposure to take that education forward. This resulted in them formalising the idea of the fellowship, where they have taken on fewer girls, but have “encompassing provisions", Virmani says, to ensure their knowledge translates to improved confidence, and helps them build a successful career.