The age-old shipbuilding town of Mandvi is flexing its history

Tucked away in the Kachchh district of Gujarat, this coastal gem has pristine beaches, historic shipyards, and the majestic Vijaya Vilas Palace

You know you are nearing Mandvi when the landscape suddenly shifts. Windmills spin in the coastal breeze and large ships line the shore, giving an ode to the town’s shipbuilding heritage. An irresistible aroma of a spiced dabeli welcomes you to this hidden gem that is tucked away in the Kachchh district of Gujarat.

Mandvi, a breezy, sun-kissed coastal town, once served as the summer retreat for the Maharao, the ruler of the erstwhile Cutch State. Its regal centrepiece, the Vijaya Vilas Palace, sprawls across 450 acres of land by the beach. Even today, part of the palace, which was built in the 1920s, remains home to royal descendants.

Vijaya Vilas Palace, a grand red sandstone structure and the iconic backdrop of the Hindi film Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam,was the first landmark I visited in Mandvi in February.

Built during Khengarji III"s reign as a summer retreat for his son, Yuvraj Shri Vijayaraji, the palace is a stately example of intricate Rajput craftsmanship. There are stone jalis made in floral and geometric patterns. Their beauty is amplified by the coloured glass windows that scatter light in a kaleidoscope of chromatics, reflecting the handiwork of craftspeople from Bengal, Rajasthan, Saurashtra, and Kachchh. Carved pillars and Bengal domes support the carved pillars. From the top balcony, you see a breathtaking view of the garden. In the in-house museum on the ground floor of Vijaya Vilas Palace, the elegance of 1920s antique furniture, silk-draped sofas, hunter trophies, and royal family portraits tells a story far richer than its fame as a film location.

Beyond the palace, the heart of Mandvi reveals itself to me through its lighterage port, which is reminiscent of its maritime heritage. It stands tall where the Rukmavati river converges with the vastness of the Gulf of Kutch. In 1580, Rao Khengarji built the Mandvi port, where merchants gathered at the fort"s bastion, Hodiyo Kotho, to watch for ships from Ceylon, Arabia, Africa, and the Malabar Coast. By the 18th century, a flag by day and an oil lamp by night signalled incoming vessels. In 1872, they added a candy-striped lighthouse, fitted with an oil wick lamp encased in an optic, to further aid maritime navigation.

Built during Khengarji III"s reign as a summer retreat for his son in the 1920s, the Vijay Vilas Palace highlights exquisite craftsmanship, with artisans from Bengal, Rajasthan, Saurashtra, and Kachchh contributing to its carved jalis, pillars, jharokhas and Bengal domes.Image: ( above) Getty Images (below) Veidehi Gite

Built during Khengarji III"s reign as a summer retreat for his son in the 1920s, the Vijay Vilas Palace highlights exquisite craftsmanship, with artisans from Bengal, Rajasthan, Saurashtra, and Kachchh contributing to its carved jalis, pillars, jharokhas and Bengal domes.Image: ( above) Getty Images (below) Veidehi Gite

Mandvi, a historic port city on Gujarat"s coast, is also the birthplace of Dabeli, a flavorful street food featuring spiced potato filling, tangy chutneys, and crunchy peanuts, wrapped in a soft bun.Image: (left) Shutterstock, (right) Veidehi Gite

Mandvi, a historic port city on Gujarat"s coast, is also the birthplace of Dabeli, a flavorful street food featuring spiced potato filling, tangy chutneys, and crunchy peanuts, wrapped in a soft bun.Image: (left) Shutterstock, (right) Veidehi Gite

Gadvi explains that the smaller ships weigh around 2.5 tonnes, while the big ones range from 1,500 to 1,800 tonnes. The largest ship, he says, weighs around 3,200 to 3,500 tonnes. Mandvi is known for its exports of spices, cotton cloth, dates, sugar and grains to Middle Eastern countries, and even Africa. But onboard, it"s not just cargo that’s transported, the guide says. “Each ship carries a crew of about 30 people. This includes four to five cooks who manage the food, another group of four to five engine room staff who maintain the machinery, and a few more who handle the steering," he says. “They’re out at sea for long stretches, often between eight to 12 hours at a time."

He continues, “The crew faces challenges with their provisions, especially fresh vegetables, which spoil quickly due to the salty air and lack of refrigeration. They usually carry essentials like dates and onions and rely on fishing to supplement their diet. The fishermen on board catch fish and cook it using the ship’s gas supply. It’s a tough but essential job, ensuring they have enough to eat during their time at sea." Gadvi says, noting that the ships in Mandvi are made from Malaysian wood due to its non-bending nature—Indian wood tends to bend over time.

After exploring several workshops at the old port and peering inside the ships under construction, we set our sights on the Bantar 72 Jinalaya. As we approach the Jain temple, Gadvi says, “When you enter the 72 Jinalaya, you’ll notice the marble floor stays cool to the touch, never heating up. This is why marble, along with granite, was chosen for its construction. The coolness of the marble provides comfort, especially for visitors who come barefoot, as is customary in Jain culture."

Bantar 72 Jinalaya temple complex spans 80 acres, with 72 white marble shrines in an octagonal design surrounding a central temple dedicated to Lord Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara.Image : Veidehi Gite

Bantar 72 Jinalaya temple complex spans 80 acres, with 72 white marble shrines in an octagonal design surrounding a central temple dedicated to Lord Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara.Image : Veidehi Gite

The temple complex spans 80 acres, with 72 white marble shrines in an octagonal design surrounding a central temple dedicated to Lord Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara. These shrines honour various Tirthankaras and feature idols from Jain pilgrimage sites across India. The main sanctum houses a six-foot idol of Adiswar Bhagwan.

Gadvi shares that the Jain Brahmins of the temple don’t use agarbatti, or incense sticks, in their rituals. Agarbattis are sometimes made out of bamboo sticks, and since the latter is used in burning dead bodies, its connection to funerary practices makes it a cultural taboo for the Jains. He continues, “There’s another reason why the agarbatti is avoided. It contains a chemical similar to firecrackers. Because of this, the Brahmins prefer to use only pure ghee made from cow’s milk." He went on to explain the alternatives they use for their ceremonies. “During significant functions like yajnas, they might use incense, but they make sure it’s free of chemicals. They use cotton to light ghee diyas (lamps), ensuring everything remains pure and traditional. The cotton used is locally grown, and the ghee is sourced from nearby villages."

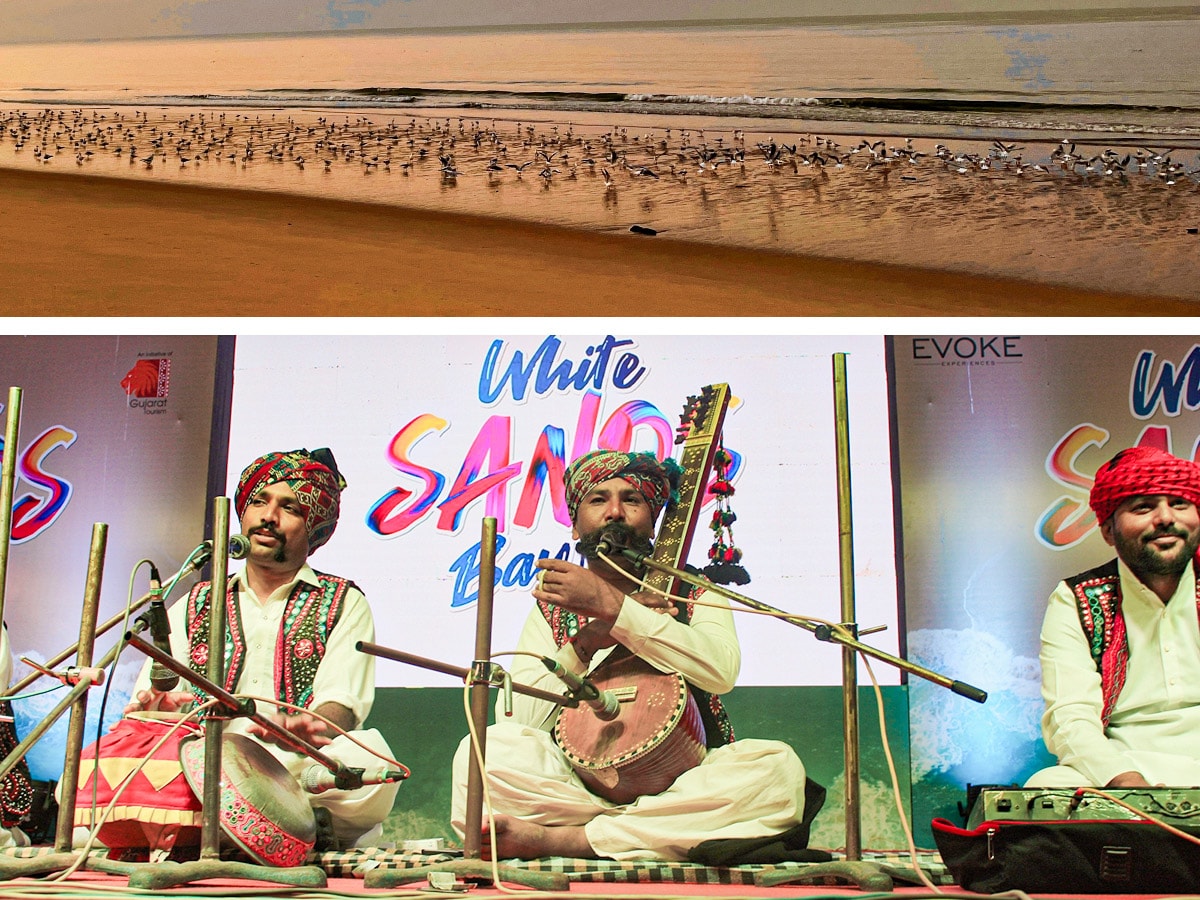

At sunrise, Mandvi Beach comes alive with the sight of hundreds of seagulls, while evenings are illuminated by lively Kutchi music performances by local artisans.Image: Veidehi Gite

At sunrise, Mandvi Beach comes alive with the sight of hundreds of seagulls, while evenings are illuminated by lively Kutchi music performances by local artisans.Image: Veidehi Gite

The leftover prasad is treated with great reverence, Gadvi says, adding that it is shared with cows and dogs to ensure that nothing goes to waste and that it all serves a sacred purpose. The 28-year-old temple feels newer, thanks to the community"s dedication to its upkeep.

After my temple visit, I retreat to my Rajwadi Suite at White Sands Bay. The resort"s private stretch of sand is blissfully secluded, with only fellow guests or the occasional flock of resident seagulls gracing the horizon during sunrises and sunsets. Evenings are a celebration of Kutchi music, blending classical, folk, and Sufi renditions, with each melody reflecting the heritage of pastoral tribes that migrated to Mandvi from Sind, Pakistan, and Central Asia, over the past thousand years. Mandvi’s closest link to the world is the airport and the train station in Bhuj, located about 56 kilometres away. The distance only adds to the town’s charm, where the past is never too far from the present.

First Published: Sep 16, 2024, 10:59

Subscribe Now