Birdwatching at Satpura National Park

Step away from the frenzy that accompanies a tiger sighting and fly with the over-300 species of birds that live in the lowlands, wetlands and mountains of Satpura National Park in Madhya Pradesh

It is a grey morning in late June, and the monsoon is slowly gaining momentum in the plains of central India. Digging my hands deep into the pockets of my windcheater, I breathe in gulps of crisp air, feel it burn my nostrils and fill my lungs. I am at the banks of the backwaters of Denwa River—which flows on the fringe of the Satpura National Park in Madhya Pradesh—waiting for my safari ticket. Soon, I will hop onto a fibreglass motorboat and cross the river to the entrance of the forest reserve.

Spread over 524 sq km across the belly of India, Satpura National Park occupies a significant part of India’s Central Highlands that cover the Malwa, Deccan and Chota Nagpur Plateaus. The park, set up in 1981, borrows its name from the Satpura Range of hills that huddle around its periphery. The rugged terrain of this central Indian forest ecosystem is home to tigers, leopards, spotted and sambar deer, nilgai (Asian antelopes), four-horned antelopes, chinkara (Indian gazelles), gaur (Indian bison), wild boars, wild dogs, sloth bears, foxes, porcupines, flying squirrels, mouse deer and the Indian giant squirrel.

The tiger dominates this list, the star that attracts tourists by the busload. But sightings of the elusive creature can be rare at Satpura. With 42 breeding adult tigers (as per the last census in 2010), it is not a Kanha or Bandhavgarh National Park—Madhya Pradesh’s more popular forest reserves that have 60 and 59 tigers respectively. Sightings of the big cat can be more tricky here. However, spurred by popular demand, safaris are almost exclusively focussed on predator cats. Sloth bears and crocodiles can bring some cheer, but if there is no big cat, the trip is considered worthless. I’ve witnessed the frenzied mayhem these big cat reserves can fuel, and want no part of it. Besides, I’m here for the birds.

The wetlands, lowlands and mountainous terrains that make up Satpura are home to more than 300 species of birds. Even wetland species thrive in this diverse ecosystem. With its proximity to the Eastern Himalayas and the Western Ghats, it serves as a passage for summer migratory birds like Indian pittas and winter migratory birds such as bar-headed geese, ruddy shelducks and great cormorants.

I hope that my fellow passengers on the jungle tour are equally passionate about birds. A safari is similar to a four-hour-long date. You are lucky if your companions share your interest. If not, exasperated sighs, clicking tongues and sometimes even loud complaints about the lack of a tiger sighting punctuate the forest’s usual sounds.

I find myself in an olive green safari jeep with our naturalist and guide Raju Gurung and four tourists who belong to a tribe I like to call ‘the urban elite’. (Full disclosure: I’m a card carrying member of this tribe.) Satpura’s deciduous forest is dense with sal, tendu (ebony), bamboo, mahua and bel (wood apple) trees that grow alongside large swathes of teak. Sal trees, still damp from the previous night’s early monsoon showers, rise from either side of the path. We take a quick turn, drive downhill on a dirt track strewn with boulders, and pass by an orange-headed thrush feasting on a hearty breakfast of termites. The monsoon showers have brought the swarmers (winged termites) out. These insects throng in hordes after a rain, drop their wings and hunt for a nesting site, that is, if they are lucky not to be some hungry bird’s dinner… or breakfast.

Image: Prathap Nair Indian Pitta: Indiapicture

Clockwise from top left: An Indian Roller bird a nightjar the Indian Pitta PeacockNot long after, as we drive along a sparsely wooded patch of the forest, we see a jungle nightjar. These birds are owl-like in appearance, crepuscular (active in twilight) and nocturnal by nature. Their grey plumage allows them to blend into the night sky, and to see one hunting during the day is rare. This jungle nightjar, however, has sacrificed its sleep to partake of the winged termites. Sensing our presence, it looks up mid-meal, a fat bunch of insects still wriggling in its bristled beak. With its black marble eyes fixed on us, it seems startled but confident in its camouflage.

Further down, in a forest stream fringed by golden brown elephant grass, we see a pair of pied kingfishers also picking on the termite swarm. These insects are not their meal of choice, but the period of feasting on fish will soon begin. The harsh north Indian summer is easing its grip on Satpura and the monsoon carries the promise of plenty. The Tawa Reservoir, which abuts the western boundary of Satpura National Park, will fill up again, supplying water and fish to the forest’s streams and rivulets. This is what the kingfishers are waiting for.

During the four-hour safari, I see the besra (a bird of prey), crested serpent eagle, brahminy starling, great tit, white-bellied drongo and white-eyed buzzard. No big cat, spotted or striped, is forthcoming the sighing and tongue-clicking grow in volume. We return to Denwa Backwater Escape, the resort I have booked myself in, and regroup for lunch. At the restaurant, which overlooks the still backwaters of the river the resort has taken its name from, we learn that another party had encountered a leopard.

Image: Prathap Nair

(Left)An Indian Roller bird and a Tickell’s blue flycatcherAs the others swap stories, I walk back to my cottage to write about the birds I had seen. Sitting in the balcony, I look up from my laptop to see a lone mahua tree by the waters, its branches whipping about in the monsoon winds. Brown-skinned cows graze on the golden grass. A peahen skitters across, her head bent, presumably looking for insects for her afternoon meal. A wary lapwing is noisily calling away at cows to prevent them from accidentally trampling her expertly camouflaged nest. Swallows brave the wind and try to fly against it. It has been a good day so far.

The idyll is interrupted by a resort guard clad in a pea-green uniform, who takes it upon himself to shoo the cattle away from the property. But it’s like trying to stop the tide: The cows come back, the lapwing screams its lungs out, and the peahen resumes its hunt for insects.

I prepare for the evening safari, and we shuffle the groups. But I still end up with the elderly gentleman from the morning trip who instructs me not to stop the vehicle far too often for birds as it ruins the chance of spotting a leopard. I pretend not to hear him and focus on the screeches of the Indian rollers preying on insects in the waning evening light. Among the birding community, their blue throat has earned them the name ‘neelkanth’, and their beauty, the acronym ABBR (Another Bloody Beautiful Roller).

Image: Prathap Nair

Image: Prathap Nair

Clockwise from left: Cheetals lock their antlers in a fight the changeable hawk-eagle a brahminy starling The evening safari proves to be a treasure trove. I see one of the most beautiful creatures that often grace the covers of most birding magazines: The Indian pitta. It is brilliantly coloured with a bold, black eye patch, white throat, green wings, shiny blue upper tail and reddish pink lower belly. This migratory bird—it breeds in the foothills of the Himalayas and the hills of central and western India and spends winter in the south—is shy by nature and can be as elusive as the tiger. Indian pittas are masters at skulking in the dense undergrowth of forests, flicking the dry leaves for insects. They are loud though, and I can hear their high-pitched ‘pree-treer’ cry. A sambar deer joins in the cacophony with its anxious call and my fellow safari companions see it as a sign of an approaching leopard. As they scan frantically for the predator, I take in an unusual sight: There are pittas everywhere, perched on the branches in the forest canopy, foraging for twigs and feasting on insects. “It is pitta season. They are nesting now,” says my guide, Raju.

Driving in the failing light, we stumble upon a one-eyed gaur that could perhaps play the role of a dashing pirate in a Hollywood rom-com. The bison’s leathery skin struggles to contain his rippling muscles. He looks at us momentarily with his one good eye before breaking contact and proceeding with chewing his cud. Jeeps and tourists with cameras are a part of his

daily routine.

A little ahead, I see a juvenile changeable hawk-eagle perched atop the low-lying branches of a gumtree, his pearl white crest whipping in the wind. He seems unmindful of our cameras, lazing on the branch catching the last of the evening sun. By now, the monsoon clouds have gathered in the darkening skies, and there is still no sign of a leopard. As we drive further on, I see a streak of orange plume and identify it as the beautiful yet tiny scarlet minivet. I stop the jeep, whip out my binoculars and catch a glimpse of the bird on a crocodile bark tree. I can hear an impatient ‘Let’s go’ from one of the jeep’s passengers. There are ‘tsks’ of disapproval.

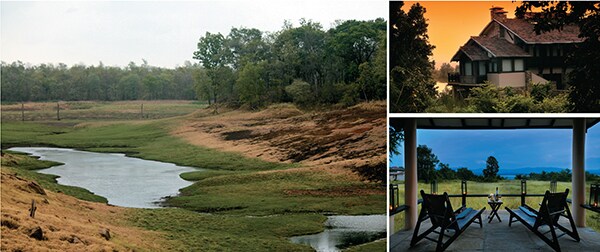

Image: Courtesy Denwa Backwater Escape

The Satpura landscape and the Denwa Backwater Escape resortBy the afternoon of the following day, displeased murmurs about indulging my need to stop and see the birds, have grown to loud complaints. I’ve become a bit of an outcast among the other guests in the resort. I doubt anyone wants me in their jeep. In the end, though, we did get to see a leopard. Jittery lapwings, skittish peacocks and alarmed langurs announced its presence. We can only see the wild cat’s menacing shadow lurking behind the mahua trees fringing a water body. It appears to be moving cautiously so as not to startle a group of cheetals (spotted deer). But we have to leave the sanctuary when the sun sets.

As we wait for the ferry to take us across the backwaters, we hear the high-pitch bark of the cheetals. The leopard has successfully run riot in the stag party, and by listening to the sounds, the naturalist concludes that it has caught its dinner. Many of the guests are disappointed having just missed an opportunity to spot a predator cat killing its prey. I, however, can’t contain a sly smile as I clutch my camera and journal: Leopard or not, it’s been a good two days for me.

First Published: Oct 17, 2015, 06:51

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Aug 13, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)