A R Rahman: A sound in the making

His music changed the country, and then took the country to the world. After 30 years of pushing boundaries in search for something new to feed his creative soul, Allah Rakha Rahman is still a work in

For a man whose music breathes life into everything it touches, AR Rahman speaks a lot about death. Not in a morbid way, but in a way that’s self-affirming, that allows you to see what you have, make the most of it, and express your creativity in a fearless, unbridled manner. When we meet at the KM Music Conservatory in Chennai on a December evening, a day after Cyclone Mandous made its landfall in neighbouring Mahabalipuram, Rahman—or Isai Puyal (roughly translates to musical cyclone), as he’s called—is under the weather. He has bloodshot eyes due to lack of sleep, and is in the throes of catching a cold.

He’s been jet-setting around the world—to Abu Dhabi for a concert to Jeddah, for a performance at the Red Sea Film Festival and to Canada and the US for the screening of his directorial debut Le Musk.

After all the rush of adrenaline, he explains, it’s been impossible to sleep.

“And one day I don’t sleep, I get sick," he says, with a chuckle, quickly adding that after a certain age, every year seems like a blessing. “You can go anytime, you know. So I feel like every year, every second, instead of cursing or doing things that are negative, try to be positive. Life is about giving, learning, sharing wisdom. It’s about facilitating things you can do for other people, whether it’s knowledge or help. And of course, music, which is the best gift."

It’s not just the past few days, but 2022 has been a “roller coaster" for the musician—“in a good way". He was live in concert at the Expo 2020 Dubai, where he mentored 50 musicians to form the first all-woman orchestra in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), called ‘Firdaus’ (‘paradise’ in Arabic). He also opened his Firdaus Studio in Dubai, which will be a base for the Firdaus orchestra and, as he puts it, “a space for collaboration among musicians across the world".

There was the premiere of Why?, a musical directed by Shekhar Kapur, sold-out concerts in the US, Canada, Europe and the UAE, apart from a roster of music compositions for films, including Mani Ratnam’s magnum opus Ponniyin Selvan: 1, Gautham Vasudev Menon’s Vendhu Thanindhathu Kaadu and R Ajay Gnanamuthu’s Cobra.

There was the premiere of Why?, a musical directed by Shekhar Kapur, sold-out concerts in the US, Canada, Europe and the UAE, apart from a roster of music compositions for films, including Mani Ratnam’s magnum opus Ponniyin Selvan: 1, Gautham Vasudev Menon’s Vendhu Thanindhathu Kaadu and R Ajay Gnanamuthu’s Cobra.

Of course, his biggest achievement of 2022, “after six years of work", he adds, was Le Musk. The 37-minute virtual reality (VR) feature film for which he turned director, is also, in a way, a testament to Rahman’s enduring love and curiosity for new technology, and his boundless creative imagination.

“It’s a cinematic sensory experience. For the first time, we’re trying to club all the technologies together. There’s VR 360, there’s 3D, motion picture, audio, ambi-sonics, scent and haptics," he says. The revenge drama is punctuated by motion picture, music, interactive seating and scent, and has got an 8.8 on 10 rating on IMDb.

While VR headsets for films is not new, Le Musk is hosted on Voyager motion chairs manufactured by Los Angeles-based VR and entertainment company Positron. “Guests sit in what looks like a half-open egg-shaped lounge chair. Once inside, they put on the VR headsets, and as they watch the VR movie, the pod moves—it turns, whirls, releases odours and provides other haptic feedback," reads a statement from the company as quoted by TechRadar. The bespoke scents for the movie are provided by Grace Boyle, who is the founder of The Feelies, a London-based studio creating multi-sensory extended reality (XR) content. She is also the daughter of Danny Boyle, director of Slumdog Millionaire, the 2008 film that won Rahman two Oscars and two Grammy awards.

Le Musk, which Rahman has also produced and scored music for, premiered at the 75th Cannes Film Festival in May. He is now figuring out how to make the VR chairs available in India. “We are starting a company to manufacture these chairs at a lower cost in India," he says.

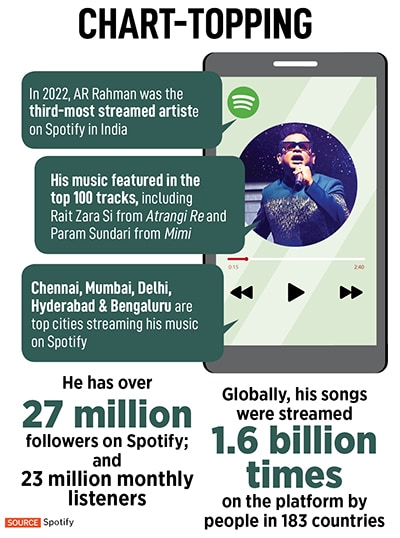

As per data from audio streaming company Spotify, in 2022, Rahman was the third-most streamed artiste on Spotify in India (following singer Arijit Singh and musician Pritam). “Music composed by him featured in the top 100 tracks, including ‘Rait Zara Si’ from Atrangi Re and ‘Param Sundari’ from Mimi," says a Spotify spokesperson. “With over 27 million followers and 23 monthly listeners, he is currently the 159th most-streamed artiste on Spotify, globally." As per global Spotify data shared by Rahman on his social media pages, his songs were streamed 1.6 billion times in 2022 across 183 countries.

Rahman, 55, has been gearing up for a long-pending concert in India, which will take place in Chennai in 2023. He is also busy finding new talents to mentor and promote. All in all, the musician, whom Time magazine famously called the Mozart of Madras, says he just cannot remain stagnant.

If you track his social media bios, they keep changing. Rahman does not identify himself as an Academy or Grammy Award-winning musician, as he once did. These days, it’s updated frequently to reflect his identity based on the current project that’s keeping him busy.

“I’ve just decided that for a creative person, the best thing is to see what’s next, rather than trumpeting past laurels. We’re proud of what we’ve done before, but we have to move on," he says. He is aware that when he performs his songs, it enables people to relive many memories, and stirs in them different emotions. And despite knowing that his songs, especially old numbers, will be appreciated as they were originally composed, he often tries to perform them in a different way. “I say, let’s play it this way and see what happens. Because as long as you are healthy and you have the energy, you should always do new things. Anything else is boring."

Because worse than being physically dead, for Rahman, is to be mentally dead. A state where you don’t know what to do, “and you’re just rotting", he says. “So to feel alive, you need to jump into the fire constantly. For the sake of rejuvenating yourself, for the sake of your team." For him, it’s always been work in progress.

(Clockwise from left) AR Rahman accepts the Oscar for Slumdog Millionaire Chiyaan Vikram, Rahman and Mani Ratnam attend the PS-1 film trailer launch Rahman performs at a concert at Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum at a backstage interview after winning at the 66th Golden Globe Awards rehearsing for the Nobel Peace Prize Concert in Oslo receiving an honorary doctorate from Berklee College of MusicImage: Clockwise: Kevin Winter / Getty Images Prodip Guha / Getty Images As Trid Stawiarz / Getty Images Sandy Young / Getty Images Kevork Djansezian / Getty Images

(Clockwise from left) AR Rahman accepts the Oscar for Slumdog Millionaire Chiyaan Vikram, Rahman and Mani Ratnam attend the PS-1 film trailer launch Rahman performs at a concert at Nassau Veterans Memorial Coliseum at a backstage interview after winning at the 66th Golden Globe Awards rehearsing for the Nobel Peace Prize Concert in Oslo receiving an honorary doctorate from Berklee College of MusicImage: Clockwise: Kevin Winter / Getty Images Prodip Guha / Getty Images As Trid Stawiarz / Getty Images Sandy Young / Getty Images Kevork Djansezian / Getty Images

Rahman’s career climb happened during the time India opened the doors of its economy to the world through liberalisation and globalisation, points out National Award-winning critic Baradwaj Rangan, who has written about Rahman’s music. It was a time when cable TV emerged and MTV, sports and other global channels opened up a whole new world of entertainment. The Indian market was flooded with global products, right from sound systems to cheap Chinese knockoffs of the original Sony Walkman and other competitively-priced devices that were easier for people to access.

“When India opened up to the world, Rahman was ready and waiting, and he made the most of it," Rangan says. “Rahman’s music inaugurated India’s entry into the global world."

Roja, his debut film directed by Mani Ratnam, released on Independence Day 1992, and captured the country’s attention with its theme centred on patriotism and the Kashmir conflict. Who can forget the visual of Rishi (played by Arvind Swami), held captive by a separatist group, falling on a burning Tricolour to put out the fire. The iconic scene was accentuated by Rahman’s scintillating score, and India got the first glimpse of a musical genius who would go on to win his first National Award at the age of 27, and then, over the next decade, take the world by storm. “At that time, there was no sound that unified India like Roja [made in Tamil and dubbed in Hindi] did. The entire album, all its songs, were blockbusters both in the South and the North,"says Rangan, who is editor-in-chief of Galatta Plus.

Musician Annette Philip, founder of the Grammy-nominated Berklee Indian Ensemble at the Berklee College of Music in the US, was an 11-year-old girl when she first heard songs from Roja. “I have a very visceral, sensory memory of the day it came on TV. The writing was uncluttered. They were tasteful, Indian melodic pieces. The compositions had this Western harmonic context, but again, uncluttered. The sparseness of the arrangement in some cases really made it stand out, and continues to do so," she says. “Of course, I was young at the time to make that distinction, but now, going back and listening to those pieces, the treatment of his post-production is really unique and shines light on where he wants it to shine."

Musician Annette Philip, founder of the Grammy-nominated Berklee Indian Ensemble at the Berklee College of Music in the US, was an 11-year-old girl when she first heard songs from Roja. “I have a very visceral, sensory memory of the day it came on TV. The writing was uncluttered. They were tasteful, Indian melodic pieces. The compositions had this Western harmonic context, but again, uncluttered. The sparseness of the arrangement in some cases really made it stand out, and continues to do so," she says. “Of course, I was young at the time to make that distinction, but now, going back and listening to those pieces, the treatment of his post-production is really unique and shines light on where he wants it to shine."

The orchestral arrangements for film score composition witnessed a turnaround with Rahman. Music writer Bhanuj Kappal says that in the ’80s and ’90s, while Illayaraja was doing a lot of classical music in Tamil cinema, there were Bappi Lahiri and others doing disco and post-disco electronics. Rahman, he says, was able to take these very different musical traditions and fuse them together. “He was one of the pioneers in terms of using new synthesisers and computer equipment to bring all these sounds and give it a fresher, more youthful energy," he says.

Music critic Jon Pareles, in his May 2015 review of Rahman’s performance at the Beacon Theatre for the New York Times, wrote that Rahman’s gift is making fusions sound natural and unforced. “A rock beat can carry a winding Carnatic-style vocals a sliding line played on a wooden Indian flute can intertwine with Western classical arpeggios from a violin," wrote Pareles. “No matter which styles he combines, Mr Rahman has an ear for yearning tunes and attention-getting hooks." In the piece, the critic also noted how the musician showed off some new technology, like a “hard-worn sensor that let him appear to tap notes out of the air".

Rahman reflects on his use of technology and says, simply, that, “Technology is nothing. It’s just like a hammer for an artiste."

For him, sound is all about intending to go to a place he’s never been before, and figuring out how to get there. “If you know where you’re going with the sound, it’s probably something you have heard or done before. But if you intend to find something new, it manifests into that," he says. For example, he says, the ending note of ‘Jiya Jale’ sung by Lata Mangeshkar for Dil Se was in a minor raga. “But Lataji ended the song in Raga Bhairavi. That was wrong, actually, but it sounded so beautiful that I kept it. So when she said, ‘Let’s go for another take’. I told her, ‘What take? We’re finished’."

Filmmaker Aanand L Rai says Rahman taught him to communicate on email. “He does not use WhatsApp or chat, and prefers email. So, in 2012, when I reached out to him, it was difficult to communicate my emotions to convince him that I’m making a beautiful story," he says. Rahman eventually came on board and made the hit album for his 2013 film Raanjhanaa. Rahman also worked with Rai for Atrangi Re in 2021.

Rai agrees that while Rahman is a “great technician", the reason his music clicks is because of his awareness of the soul. “When, as a director, you narrate your vision to him, it’s not the words or the scene or the structure he is catching, but the feelings. That’s why when you listen to his music, it reaches deep down inside." Instruments and technology, he adds, are the tools he uses, possibly better than others, to reach there.

Rahman—who lost his father, a music composer, at 9 and had to soon turn breadwinner for his mother and three sisters—credits his success to his mother, Kareema Begum. She had sold her jewellery so that he could set up his studio, the Panchathan Record Inn, in the late 1980s. Rahman always enters his studio barefoot, just like entering one’s home, or a place of worship. And since then, sound has been the way for Rahman to transcend himself.

“Some interpretations of religion say that music is not good for you because it makes you forget God. Actually, no, it is how you make the music. There’s music that’ll make you remember God," he says. In fact, when people of different faiths tell him they see God when they listen to his music, “that’s the ultimate compliment".

For the introverted, elusive and shy person that he is, Rahman’s success, in part, has also been in his ability to effectively collaborate with others. From Mick Jagger and Joss Stone to various senior and upcoming Indian artistes.

“He’s patient and open. Those are two great qualities to have," says Vasundhara Das, who started her playback singing career with Rahman with the Tamil song ‘Shakalaka Baby’ for the film Mudhalvan, and has worked with him for iconic numbers, including ‘O Re Chhori’ from Lagaan, and ‘Kahin Toh’ from Jaane Tu…Ya Jaane Na. According to her, when Rahman composes music for a film, he has a clear vision about where he wants the audio to go. At the same time, he also has the maturity and trust to give his musicians and collaborators the creative freedom they need in order to innovate.

“He’s patient and open. Those are two great qualities to have," says Vasundhara Das, who started her playback singing career with Rahman with the Tamil song ‘Shakalaka Baby’ for the film Mudhalvan, and has worked with him for iconic numbers, including ‘O Re Chhori’ from Lagaan, and ‘Kahin Toh’ from Jaane Tu…Ya Jaane Na. According to her, when Rahman composes music for a film, he has a clear vision about where he wants the audio to go. At the same time, he also has the maturity and trust to give his musicians and collaborators the creative freedom they need in order to innovate.

Philip remembers how he is also extremely quick on his feet. She recollects a time when he asked her to write a Western classical fugue. She told him she’ll think about it later that night, and he instantly started playing a tune on his piano. “He sat on the piano and just made it up, right there, so quickly and easily." Philip feels it speaks to his depth of knowledge, and how he has taken time to study not only classical—both Hindustani and Carnatic—but also Sufi, and folk music. Philip adds that while Rahman is wise and reserved, he is also a playful person who is always down for a laugh and has “not lost his inner mischief". This, she feels, also reflects in his music.

Rahman, who had to drop out of school to pursue his career in music, received a scholarship to study Western classical music at Trinity College, Oxford.

Rahman has managed to balance the constrictions of commercial films with his personal creative expression, follow protocols and be a rebel at the same time. Das remembers how, while recording with Rahman, there would be loads of laughter. And even when he was getting his vision to match with the director of a film, he would not get fussed about someone not liking what he has made.

He would also push his artistes out of their comfort zone. “He would want me to push it to a point that my voice cracked. He wants to make you reach your absolute limits, and then he wants more," Das says. In a country that wants women to have demure voices or sound a certain way, Rahman was never looking for that, she adds. “He realises that women have different voices and we don’t all need to sound like Lataji or Ashaji."

Rahman confesses that he also gets angry. “I’m always angry. You ask my team and they’ll run away," he says, laughing. “But my anger is not personal, ego anger. As a team leader, sometimes you have to shout or be strict, so you get the job done. Because if I falter or one of the team members falters, we all fall. That’s not a cool thing when people trust you."

Kappal says Rahman’s sounds, even if they are not contemporary, do not sound dated, in a way that a lot of other music from that era does. Although it’s not a given for anyone at this point, he believes that, “There’s a good chance Rahman will still be one of the top names in music 15 to 20 years down the line."

Rahman feels a musician comes of age when he can manifest what the thinks into reality. “That happened for me even with my first movie. Since then, it’s not about getting better or worse, but just going in different directions to see what else I can explore."

See full list of Showstoppers 2022-23

And these directions are as varied as writing and producing films, as he did with 99 Songs in 2019, or directing one. It also means opening up spaces for collaborations, teaching and mentoring young musicians.

There comes a time in life, when you feel like you can do anything just because you want to, Rahman says. And that time, for him, seems to be now. There are occasions, he says, when his wife Saira asks him if he’s sure of what he’s doing. He’s not, but he’s not scared either.

“Even when we had no money, at a time when music was considered an unsafe profession, my mother, who had lost her husband in her 20s and was single-handedly raising four children, had the courage to ask me to pursue music," he says. “I realised early on that playing safe is the most unsafe [thing to do]. And once you overcome the fear of death, nothing is scary. You can do anything."

First Published: Jan 06, 2023, 11:04

Subscribe Now