WASHINGTON — Boeing’s chief executive faced the grieving relatives of two deadly crashes of its 737 Max jet at an emotional congressional hearing Tuesday, as senators pummeled him with questions about whether the company should have grounded the plane before the second accident.

At times looking shaken, the executive, Dennis A. Muilenburg, said that if he could do it over again, he would have acted after the first crash, off the coast of Indonesia last October. “If we knew everything back then that we know now, we would have made a different decision,” he testified. He said Boeing officials had asked themselves “over and over” again why they didn’t ground the plane sooner.

“I think about you and your loved ones every day,” Muilenburg told the families, who at one point stood behind him holding up large photographs of the dead.

Still, Muilenburg acknowledged for the first time that he knew before the second crash that a top pilot had voiced concerns about the plane while it was in development. The admission will most likely lead to more questions about why Boeing did not act more decisively before that crash, of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, on March 10.

Two days later, Muilenburg called President Donald Trump to defend the safety of the Max. The plane was grounded, however, March 13, although the United States waited longer than most countries to act.

The two accidents killed 346 people and have thrown the company into crisis and roiled the global aviation industry.

Muilenburg, who had spent weeks preparing for his appearance, was measured throughout more than two hours of testimony. He mostly avoided being cornered by senators’ lines of questioning, and declined to agree to demands that he endorse proposals to reform aviation laws.

The hearing was held on the anniversary of the crash of Lion Air Flight 610, in Indonesia. The mood in the hearing room was tense. Multiple senators asked Muilenburg to address families of crash victims seated behind him.

The chief executive, who has been criticized for failing to convey sympathy after the crashes, apologized to the families directly in his opening remarks.

“We are sorry,” he said. “Deeply and truly sorry.”

During several tense exchanges, senators on the commerce committee sharply criticized Boeing’s handling of the situation. Muilenburg said in opening remarks that the company had “made mistakes,” and he vowed to redouble its focus on safety.

Boeing faces multiple federal investigations into the design of the plane, including a criminal inquiry led by the Justice Department.

Among the most intense rounds of questioning concerned messages that a pilot central to the development of the Max sent to a colleague in November 2016, months before the plane was certified by regulators.

The pilot, Mark Forkner, said in the messages that he had “unknowingly” lied to the FAA about the system, which was “running rampant” in the flight simulator and causing him trouble. The system, known as MCAS, ultimately contributed to both crashes. Boeing provided the messages to the Justice Department in February, though it did not give them to lawmakers or the FAA until this month.

Muilenburg said he became aware of Forkner’s messages “prior to the second crash.”

In January 2017, two months after his exchange with a colleague, Forkner sent an email to the FAA reiterating an earlier request that the regulator remove mention of MCAS from pilot training materials.

“Delete MCAS,” Forkner wrote in the email, which was reviewed by The New York Times. He described the system as “way outside the normal operating envelope,” meaning that it would activate only in rare situations that pilots would hardly ever encounter in normal passenger flights.

Muilenburg said he “didn’t see the details of this exchange until recently.” He added that the company was “not sure” what the pilot meant in the messages to his colleague and noted that the company had not been able to speak to Forkner, who now works for Southwest Airlines.

“You’re the CEO the buck stops with you,” said Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, adding, “How did you not in February set out a nine-alarm fire to say ‘we need to figure out exactly what happened,’ not after all the hearings, not after the pressure but because 346 people have died and we don’t want another person to die?”

Muilenburg, who appeared alongside Boeing’s chief engineer, John Hamilton, remained stoic as lawmakers took turns jabbing at the company and its signature airplane. The senators pressed Muilenburg to account for seemingly lax oversight by the FAA, haranguing him about the close relationship between the aerospace giant and its regulator.

In a report released this month, Indonesian investigators said that errors by the flight and maintenance crew contributed to the crash. But they blamed Boeing for designing a system that triggered repeatedly based on a single sensor and failing to notify pilots that it existed. A task force of nine international regulators said in a separate report that Boeing never fully explained the system to regulators, who relied heavily on the company to help certify the plane and did not have the expertise in place to adequately assess the information it did receive.

An earlier investigation, by the National Transportation Safety Board, found that the company had underestimated the effect that a malfunction of MCAS would have on the cockpit, wrongly assuming that pilots would immediately counteract an erroneous firing.

As the 737 Max was developed, Boeing employees working on behalf of the FAA, not government inspectors, signed off on many aspects of the plane. This system of so-called delegation, which lets manufacturers approve their own work, is now under scrutiny.

Boeing employees in its Seattle-area and Charleston, South Carolina, plants have said they sometimes felt pressure to meet deadlines while conducting safety approvals. Investigations by The New York Times have revealed that key FAA officials didn’t fully understand MCAS and that the regulator at times deferred to the company, making decisions based on how much they would cost Boeing and its production schedule.

“Boeing lobbied Congress for more delegation, and now we have to reverse that delegation,” Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., said, referring to the company’s push to pass legislation that undercuts the role of the FAA in approving airplanes.

“I would walk before I was to get on a 737 Max,” said Sen. Jon Tester, D-Mont., adding, “You shouldn’t be cutting corners, and I see corners being cut.”

On Wednesday, Muilenburg will appear in front of the House transportation committee, which has been leading the congressional investigation into the Max and is expected to adopt an even more adversarial stance. His appearances mark the first time a Boeing executive has addressed Congress about the crashes.

Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., chairman of the transportation committee, will add a new piece of information, saying that Boeing engineers at one point proposed placing an MCAS alert inside the cockpit, according to a copy of his opening statement. No such alert was ever installed, though, and DeFazio plans to press Muilenburg on why that decision was made.

Inside Boeing, Muilenburg’s performance in front of Congress is seen as a key test of whether he will remain in his post as chief executive, as the board weighs further management changes.

This month, Boeing dismissed the executive in charge of its commercial division, Kevin McAllister, and stripped Muilenburg of his title as chairman, in a sign that the board is moving more urgently toward holding senior leadership accountable for the crisis.

Nadia Milleron, whose daughter Samya Stumo died in the Ethiopia crash, sat three rows behind Muilenburg at the hearing and said she believed “he should resign” and “the whole board should resign.”

As Muilenburg left the room at the end of his testimony, Milleron asked him to “turn and look at people when you say you’re sorry.”

He turned around and looked her in the eye.

“I’m sorry,” he said.

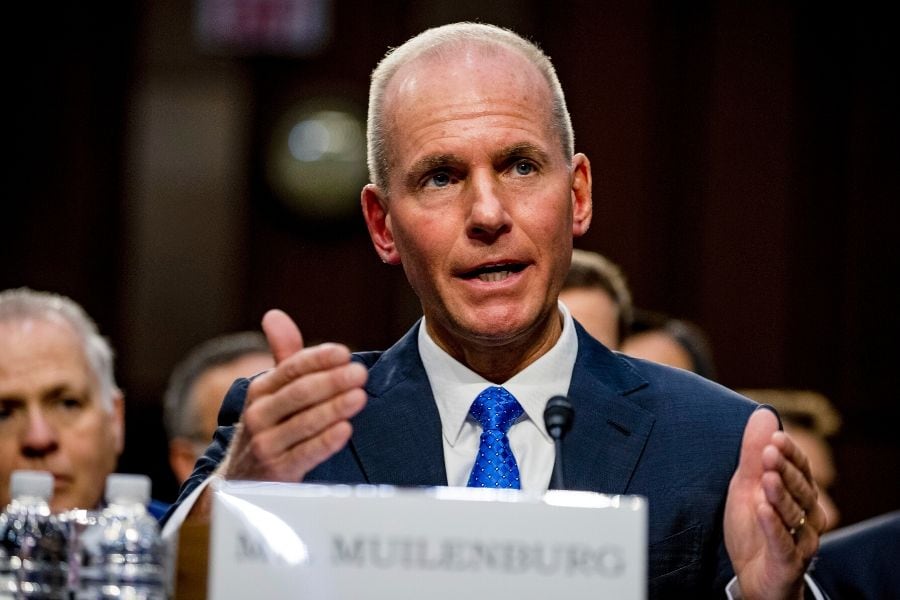

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg testifies before a hearing Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington on Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2019, about aviation safety and the future of the Boeing 737 MAX airplane. Muilenburg, is testifying before Congress for the first time since the crashes of two 737 Max jets that killed 346 people

Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg testifies before a hearing Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington on Tuesday, Oct. 29, 2019, about aviation safety and the future of the Boeing 737 MAX airplane. Muilenburg, is testifying before Congress for the first time since the crashes of two 737 Max jets that killed 346 people