It's never been easier to be a CEO, and the pay keeps rising

A New York Times survey shows that in 2018, CEO pay in the US increased at almost twice the rate of ordinary wages

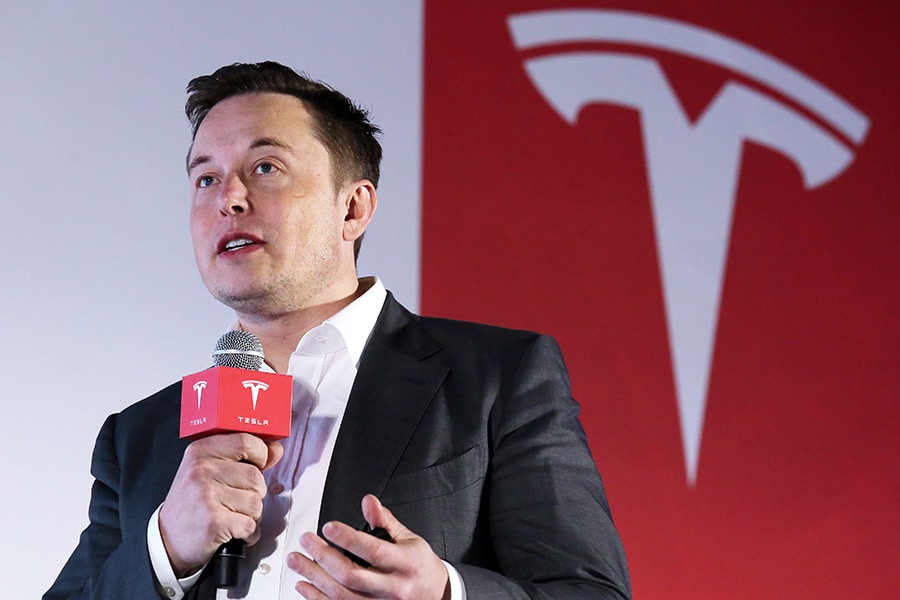

Image: Nora Tam/South China Morning Post via Getty Images[br]This is not a difficult time to be a chief executive.

Image: Nora Tam/South China Morning Post via Getty Images[br]This is not a difficult time to be a chief executive.

The solid economy has bolstered companies’ sales, and President Donald Trump’s corporate tax cuts have juiced profits. A huge increase in stock buybacks has lifted share prices.

Despite all the structural forces aiding companies’ bottom lines and stock prices, boards continue to act as if CEOs have unique powers to deliver better returns — and have gone to great lengths to compensate them. The most prominent example: Tesla approved a pay package to Elon Musk valued at as much as $2.3 billion. It’s not just the highest sum for last year it’s the biggest ever, according to compensation experts. (More on Musk below.)

Something about this feels inevitable. Every year, Equilar, an executive compensation consulting firm, conducts a survey for The New York Times of the 200 highest-paid chief executives in America. And nearly every year, CEOs already earning huge sums get even bigger payouts. In 2018, our analysis shows, they did particularly well: The median boss received compensation of $18.6 million — a raise of $1.1 million, or 6.3%, from the year prior.

CEO pay increased at almost twice the rate of ordinary wages. In 2018 — a pretty good year for the labor market — the average American private-sector worker got a 3.2% raise, or an extra 84 cents per hour.

These gains at the top are despite recent efforts to restrain CEO pay. Earlier this decade, Congress required that companies disclose the ratio of their chief executive’s pay to that of their median employee. Lawmakers also gave shareholders a special but nonbinding vote on the matter. Another trend theoretically contributing to accountability is that company boards, under pressure from some shareholders and advisory firms, have tied a lot more of a chief executive’s pay to a company’s performance.

And yet the compensation machine still spits out bigger and bigger rewards. Musk topped Equilar’s list by more than $2 billion. In second place was David M. Zaslav, the chief executive of Discovery, an entertainment company, at $129.5 million.

Palo Alto Networks, which provides cybersecurity services, gave its incoming chief, Nikesh Arora, a package that it said was worth $125 million. Oracle awarded each of its two co-chief executives payouts of $108 million and gave its chairman, Larry Ellison, slightly more. One of the co-CEOs, Safra A. Catz, was 2018’s highest-paid woman, one of only eight on the Equilar list.

Uber’s chief executive, Dara Khosrowshahi, who got a $45.3 million award, would have been 10th on Equilar’s list. But since the company was not public last year, it was not included in the rankings. Also missing: the CEOs of private equity firms and hedge funds, whose compensation can run into the hundreds of millions.

Five take-aways from the 2018 report:

CEOs get paid regardless of logic

When Tesla announced its multibillion-dollar award for Musk in January 2018, it was hailed as a bold experiment, fitting of a visionary entrepreneur. Sure, the multibillion headline number was big enough to appease the gods, but the award was structured in such a way that Tesla would have to reach highly ambitious milestones for Musk to receive any of it. Tesla’s market capitalization is now $35 billion. To gain all the options in the award, its market value would have to increase 18 times over, to $650 billion.

“Elon’s entire compensation is directly tied to the long-term success of Tesla and its shareholders, and none of the equity from his 2018 performance package has vested,” said Kamran Mumtaz, a spokesman for Tesla.

The award’s structure was driven by concern that Musk’s attention could wander to his other ventures, like SpaceX, or that he could leave Tesla altogether. In describing the compensation package, the board said it wanted to “motivate Mr. Musk to continue to not only lead Tesla over the long term, but particularly in light of his other business interests, to devote his time and energy in doing so.”

In the months after Musk’s focus was supposedly fortified, however, both he and the company faltered. The company struggled to produce and deliver its electric cars, senior executives departed and financial concerns returned. Musk posted messages on Twitter about a deal to take Tesla private that the Securities and Exchange Commission later described as false and misleading. (Both Musk and Tesla settled with the agency.)

Why grant Musk the award at all? Analysts for Institutional Shareholder Services said at the time that because Musk already owned roughly a fifth of Tesla, his financial interests were already strongly aligned with the company. If its value hits $650 billion, his stake could be worth more than $100 billion, so it’s unclear what extra incentive a $2.3 billion carrot provides. Jeff Bezos, Amazon’s chief executive, did not require huge additional equity grants to inspire him to build his company.

CEOs get paid extra to do the basics

Two chief executives who ended high up on Equilar’s list, Robert A. Iger of Disney and John J. Legere of T-Mobile, are getting awards for leading their companies through large mergers.

But carrying out mergers could be considered a core part of a CEO’s job description, and not deserving of extra pay. CVS, for instance, gave a few senior executives a special award for overseeing its big merger with Aetna, but its chief executive, Larry J. Merlo, did not get one.

Iger of Disney is getting extra shares that Equilar values at nearly $74 million, an award that was dependent on the completion of Disney’s acquisition of 21st Century Fox and is subject to performance goals. Adding that sum to the $65.6 million that Iger was awarded last year would give him a combined haul of nearly $140 million.

Abigail Disney, a granddaughter of Roy O. Disney, who founded Disney in 1923 with his brother, Walt Disney, recently tore into the company’s pay practices. “He deserves a lot of money I’ve never quibbled with that,” she said, referring to Iger’s compensation. “But the question is how far we’re going to go.”

David J. Jefferson, a spokesman for Disney, said the boards of both Disney and 21st Century Fox had requested that Iger extend his employment agreement to oversee the merger. He added that the stock award for completing the deal “will only reach target value if Disney delivers strong performance through 2021.”

Legere, whose company is combining with Sprint, stands to get a special merger award that T-Mobile valued at $37 million. He’ll get it even if the deal does not close. In its proxy, T-Mobile said the stock grant was designed to push recipients to maximize returns for T-Mobile shareholders even if the company did not merge with Sprint.

CEOs get paid regardless of scandal

Timothy J. Sloan stepped down from Wells Fargo in March, after struggling to convince Congress and regulators that the bank was fixing its problems after several scandals. Sloan’s stock grants, worth around $24 million, according to Equilar, will vest over the next three years, Wells Fargo said.

Facebook had a horrible 2018. The Cambridge Analytica scandal revealed the company’s poor controls on user data, and the activity of Russia-linked actors on Facebook around the time of the 2016 election was one of the biggest outrages to ever hit a large technology company. The company is now spending billions trying to make its network secure, and it faces regulatory scrutiny that could affect it for years.

But executive compensation barely took a hit. Facebook’s board gave an $18.4 million stock award to both Sheryl K. Sandberg, the chief operating officer, and Mike Schroepfer, the chief technology officer. (Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook’s chief executive, is not paid like the other senior executives effectively all his compensation is made up of payments to cover the costs of travel and personal security.)

CEOs often get paid more than companies say

Equilar does its analysis based on headline compensation numbers from proxy statements. But those are estimates, often based on companies’ complex calculations of what stock and options grants will be worth in the future. Some shareholder advisory analysts do their own math and conclude that the awards are likely to pay out far more than companies claim.

Institutional Shareholder Services, for instance, estimated that the 2018 compensation granted to each of Oracle’s co-CEOs had a value of $207 million, compared with the $108 million in the proxy. ISS’ calculations sometimes differ because they make different assumptions about whether executives will achieve performance targets. (Oracle declined to comment.)

Of course, executives may end up earning a lot more than the headline number because their firms performed exceptionally well. Jamie Dimon, the chief executive of JPMorgan Chase, came 22nd in Equilar’s 2018 ranking. He got an award in 2016 that, at the time, was valued at $20.5 million. At the end of the payout’s performance period in January, in part because Dimon hit his higher performance goals, the grant was actually worth $56 million, according to Equilar’s calculations.

Failure is possible, though. Just as executives can earn far more than originally estimated, an award can end up being worth zero. For example, a performance-based award Iger received in 2014 was valued at $60 million, but because Disney’s operating income fell short of a target, he did not collect. Zaslav also failed to get all of a 2014 package originally valued at $145 million the award actually paid out $65 million. Zaslav can perhaps afford to shed some pay given the starting size of his awards the last three had a combined value of nearly $209 million.

CEOs get paid to invest in their companies

Upon joining Palo Alto Networks last year, Arora took $20 million of his own money and purchased company stock. When chief executives invest a portion of their fortunes, it can strengthen the alignment between the top executive and shareholders. (Famously, before he joined Bank One in 2000, Dimon spent roughly $57 million buying shares in the bank, which later merged with JPMorgan Chase.)

But this incentive may not be as strong in Arora’s case. The $20 million is a relatively small proportion of his total 2018 compensation, valued at $125 million. What’s more, Palo Alto matched his cash investment with an award of restricted stock. (“Mr. Arora’s performance-based equity award provides value to Mr. Arora only if our stockholders realize significant value,” said Ben Malloy, a company spokesman.)

First Published: May 27, 2019, 11:07

Subscribe Now