They want something — a whisk, diapers, that dog toy — and they turn to Amazon. They type the product’s name into Amazon’s website or app, scan the first few options and click buy. In a day or two, the purchase appears on their doorstep.

Amazon has transformed the small miracle of each delivery into an expectation of modern life. No car, no shopping list — no planning — required.

But to make it all work, Amazon runs a machine that squeezes ever more money out of the hundreds of thousands of companies, from tiny startups to giant brands, that put the everything into Amazon’s Everything Store.

In more than 60 interviews, current and former Amazon employees, sellers, suppliers and consultants detailed how Amazon dictates the rules for those businesses, sometimes changing those rules with little warning. Many spoke on the condition of anonymity, for fear of retaliation by Amazon.

Amazon punishes the businesses if their items are available for even a penny less elsewhere. It pushes them to use the company’s warehouses. And it compels them to buy ads on the site to make sure people see their products.

All of that leaves the suppliers more dependent on Amazon, by far the nation’s top online retailer, and scrambling to deal with its whims. For many, Amazon eats into their profits, making it harder to develop new products.

“Every year it’s been a ratchet tighter,” said Bernie Thompson, a top seller of computer accessories who Amazon has highlighted in its marketing to other merchants. “Now you are one event away from not functioning.”

Many sellers and brands on Amazon are desperate to depend less on the tech giant. But when they look for sales elsewhere online, they come up short. Last year, Americans bought more books, T-shirts and other products on Amazon than eBay, Walmart and its next seven largest online competitors combined.

“The secret of Amazon is we’re happy to help you be very successful,” said David Glick, a former Amazon vice president who left the company last year. “You just have to kiss the ring.”

Amazon says that its operation is so massive, the rules are necessary to give customers a quality experience. The company said the health of sellers was a top priority, and that it had invested billions of dollars to support them. It said that about 200,000 sellers surpassed $100,000 in sales in 2018, roughly a 40% increase from the year before.

“If sellers weren’t succeeding,” said Jeff Wilke, the chief executive of Amazon’s consumer business, “they wouldn’t be here.”

Amazon has faced harsh criticism in the past for displacing Main Street brick-and-mortar retailers. Now, the diverging fortunes of Amazon and many of the companies selling products on its own site are at the heart of the antitrust scrutiny Amazon faces. Investigators at the Federal Trade Commission and the House Judiciary Committee are examining whether Amazon abuses its position as the central online connection between people making products and those buying them.

Lured Into Shipping

When Amazon opened its doors to sellers, the fulfillment industry — for storing, packing and shipping online orders — was in its infancy. Many top sellers on Amazon ran their own warehouses.

Seeing a competitive advantage in offering faster delivery times, Amazon opened cavernous warehouses near major cities. The expansion left Amazon with extra space to fill, and the company turned to sellers. It pitched them on the idea of paying Amazon to store and ship their products, even those sold on other sites.

Many sellers say that the company charges fair rates to fulfill Amazon orders. But they say Amazon is charging them higher prices for other services. For example, because the warehouses operate near capacity, the company charges several times more than competitors to store items before they ship out.

The costs can be several times higher for sellers who use Amazon to ship orders made on other websites. Amazon charges $13.80 for one-day shipping on a T-shirt bought on a site other than Amazon, versus $3.68 when bought on Amazon.

Price Control

This summer, Brandon Fishman, the founder of VitaCup, a startup that infuses coffee with vitamins and nutrients, saw a promising opportunity.

Zulily, an e-commerce site that offers low prices in exchange for slower shipping, wanted to list VitaCup’s products 30% off for a short time. It was a chance for Fishman, whose 35-employee company gets the majority of its sales through Amazon and its own site, to reach new customers.

But Amazon’s software noticed the lower price and removed the bright “Buy Now” and “Add to Cart” buttons from its site. When those buttons are gone, shoppers get a bland text link that says, “Available from these sellers” and they must make more clicks to purchase an item. Those extra clicks are often the difference between success and failure for a seller.

Fishman’s Amazon sales tumbled, and he emailed Zulily to quickly take down the listing. “I have told them about my rage many times,” Fishman said of Amazon. “It has not changed them.”

Resigned Partners

A decade ago, Thompson, a former Microsoft software developer, recognized a big market for computer accessories like computer docking stations and cables. He started Plugable and betted big that depending on Amazon would turn his idea into a business.

It worked. In 2016, Amazon founder Jeff Bezos highlighted Thompson when talking about the success of sellers in his annual letter to investors. Amazon posted a video about Plugable on its website to attract new sellers.

One Sunday in July 2019, he got an email saying that Amazon had removed the docking stations. Amazon said it was because of complaints that Plugable’s products had not matched the condition described on the site.

Other docking stations, including one made by Amazon, filled the void online.

Thompson scrambled, contacting two high-level managers he knew and his account manager, who Amazon charges him $5,000 a month to have. None of them could fix it. He and other staff members dug through customer feedback and returns. They found only outstanding reviews.

After four days and at least $100,000 in lost sales, the listing went back up. Thompson said he still did not understand what ignited the problem.

“We really built the company on Amazon,” Thompson said. “But today our focus has to be getting diversification off Amazon.”

He said he understood what he was up against. “We are dealing with a partner,” he said, “who can and will disrupt us for unpredictable reasons at any time.”

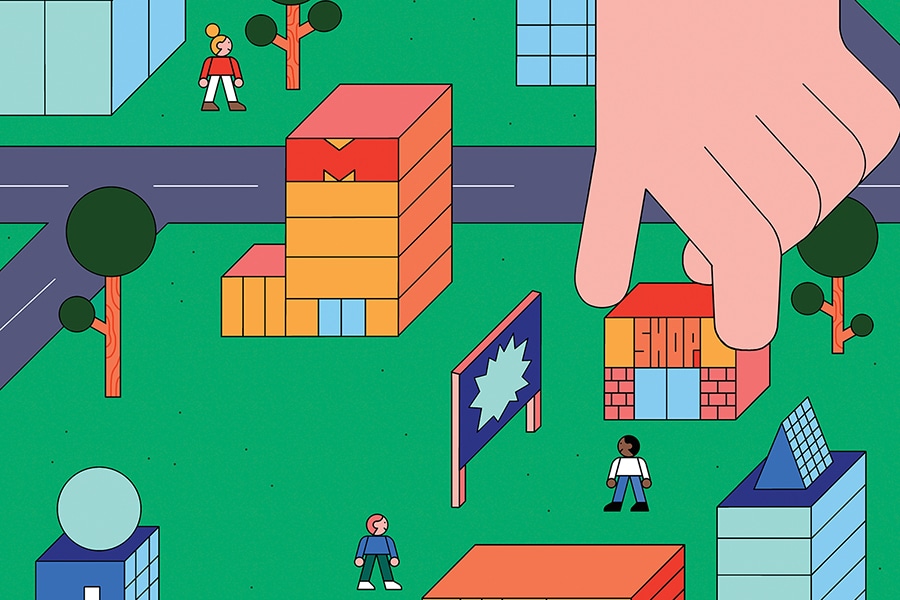

Twenty years ago, Amazon opened its storefront to anyone who wanted to sell something. Then it began demanding more out of them. (Andrea Chronopoulos/The New York Times)[br]SEATTLE — For tens of millions of Americans, it is so routine that they don’t think twice.

Twenty years ago, Amazon opened its storefront to anyone who wanted to sell something. Then it began demanding more out of them. (Andrea Chronopoulos/The New York Times)[br]SEATTLE — For tens of millions of Americans, it is so routine that they don’t think twice.