Can Koo be King? Perhaps with better content moderation

Koo, the new bird app on the block is supposedly India's answer to Twitter; Forbes India delves deep into the app and its content moderation policy

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock

At the height of the back and forth between the Indian government and Twitter about the latter’s refusal to block accounts of journalists and activists, Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal publicly threw his weight behind another app—Koo. On February 9, Goyal tweeted, “I am now on Koo. Connect with me on this Indian micro-blogging platform for real-time, exciting and exclusive updates. Let us exchange our thoughts and ideas on Koo."

Within two days, the microblogging platform with a yellow bird for a logo, started seeing 20 to 30 times the number of downloads it used to have otherwise. Torn in a number of directions due to the “sudden surge in the number of users", since then, the team has barely slept, CEO and co-founder of the app, Aprameya Radhakrishna, told Forbes India. This is the first time the 10-month-old platform had seen such “crazy spikes". “Before this, [there were] many small, manageable spikes but no big spikes," he said. One was when the app won the Aatmanirbhar Bharat App Innovation Challenge in August another when Google PlayStore listed Koo as one of the Best Everyday Essentials apps from India in December.

A Twitter alternative, the app now has about 3 million downloads across iOS and Android, as per Radhakrishna.

The 40-member team—which consists of engineers, community managers, growth and product managers, finance, partnerships, admin—has been “trying very, very hard that all users have a great experience". The sudden growth means that the team is finding it difficult to make sure that the servers are up “but we are working on it, as in, we are getting all the people involved", Radhakrishna said.

The aim of the app is very clear—to give every internet-using Indian a voice on the internet. “We saw that any other app was only giving voice to English-knowing Indians. When it came to Indian language speaking Indians, who are not so comfortable with English, there was no way they could express themselves freely because there was no app for it and that’s where we operate," Radhakrishna said. Koo is currently available in six languages—English, Hindi, Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Marathi. It will soon introduce 12 more Indian languages. All its AWS servers are located in Mumbai.

“We are not yet making any revenue. We are a 10-month-old company looking to grow our user base," Radhakrishna said. The app is available to everybody across the world except in Europe. This is because of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that Koo is in the process of complying with, he adds.

Content moderation

The world’s largest social media platforms—Twitter and Facebook—are still struggling with moderating content online. Koo’s sudden popularity can, in fact, be partly attributed to Twitter and the Indian government’s diverging opinions about what content should be taken down from a platform and what constitutes free speech.

While Koo has a content moderation policy, it is not yet available online. “We are a young company we are in the process of getting these things together formally," Radhakrishna said. But there are certain lines that are obvious to him—“if there is a mention of self-harm or if there is incitement of violence, that is where there is the possibility of loss of human life, that is when it is critical to act and to abide by the law of the land."

Radhakrishna did not say whether the platform would take the content down itself or if it would wait for a court order or a Section 69A blocking order from the government. “We haven’t faced a situation like that yet [received a court order or a Section 69A blocking order] so we will have to look at the exact Koo or post that is being spoken about because I can’t give a generic ‘I will do this, I will do that’ without a particular actual incident," he said.

Bigger platforms like Facebook, Twitter and Google release biannual transparency reports wherein they detail the number of government requests and court orders they have received over the period. They also detail the volume and type of content that they have taken down using automated tools and that which they have restored. Indian messaging app ShareChat, too, has released one transparency report. Koo also plans to do that.

“We will always be 100 percent transparent about all our dealings. There will be nothing hidden. We want to give assure users that they can use the platform safely. Facebook, Twitter, Instagram are multibillion dollar companies and hence they have everything in place. Being small is not an excuse, but we just need a little time because all this has come suddenly and we will gather ourselves and make sure all of this is complied [with]," Radhakrishna said.

Is Koo taking a reactive approach to content moderation?

Currently, when a user reports a Koo (the equivalent of a tweet) to the platform, it is reviewed by human community managers.

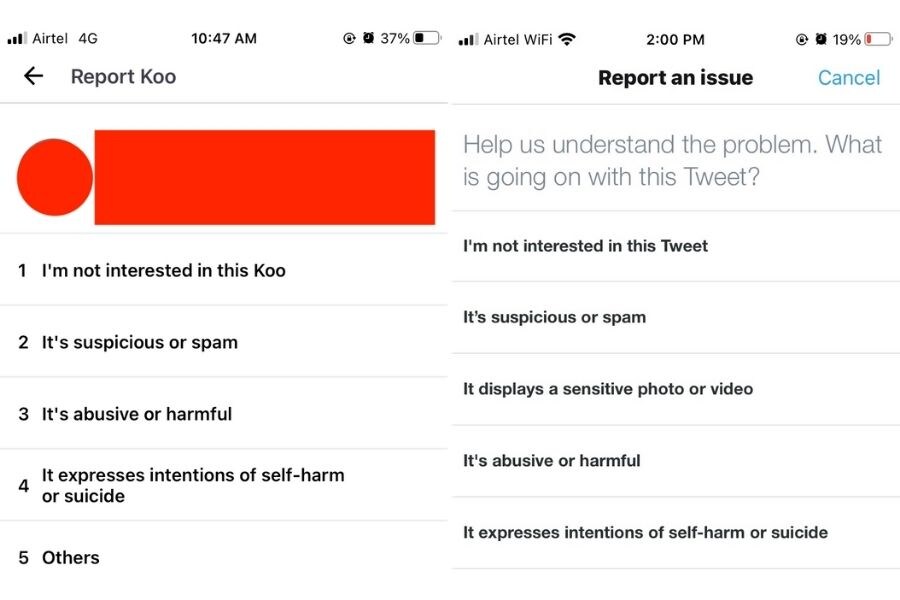

The reasons for flagging a Koo are mostly the same as on Twitter—‘I’m not interested in this Koo’, ‘It’s suspicious or spam’, ‘It’s abusive or harmful’, ‘It expresses intentions of self-harm or suicide’, and ‘Others’. Koo, unlike Twitter, does not list ‘It displays a sensitive photo or video’ or ‘It expresses intentions of self-harm or suicide’. Misinformation is not listed as a reason for reporting on either of the two platforms.

But at scale, Koo will need to use technology else moderation will not be possible. “We will use technology to flag certain usage of words and then have a human look at it in certain cases," Radhakrishna said.

Radhakrishnan pointed out that until the explosive growth of Koo earlier this week, the platform did not face the problem of misinformation. “We were at a scale where we could handle it. Right now, we will have to put in some processes so that we can handle the scale. We currently depend on the community to report problematics Koos for out ream to look at. We will start working with fact-checkers to make sure we know exactly what we are doing," he says. Koo has currently not tied up with any fact-checkers, nor does it allow users to flag content for misinformation.

At a regulatory level, in 2018, the government had proposed amendments to the rules governing intermediaries under the Information Technology Act but these rules have still not been notified and brought into effect. The proposed changes would make it mandatory for any intermediary to use automated tools to “proactively identify and remove or disable public access to unlawful information or content".

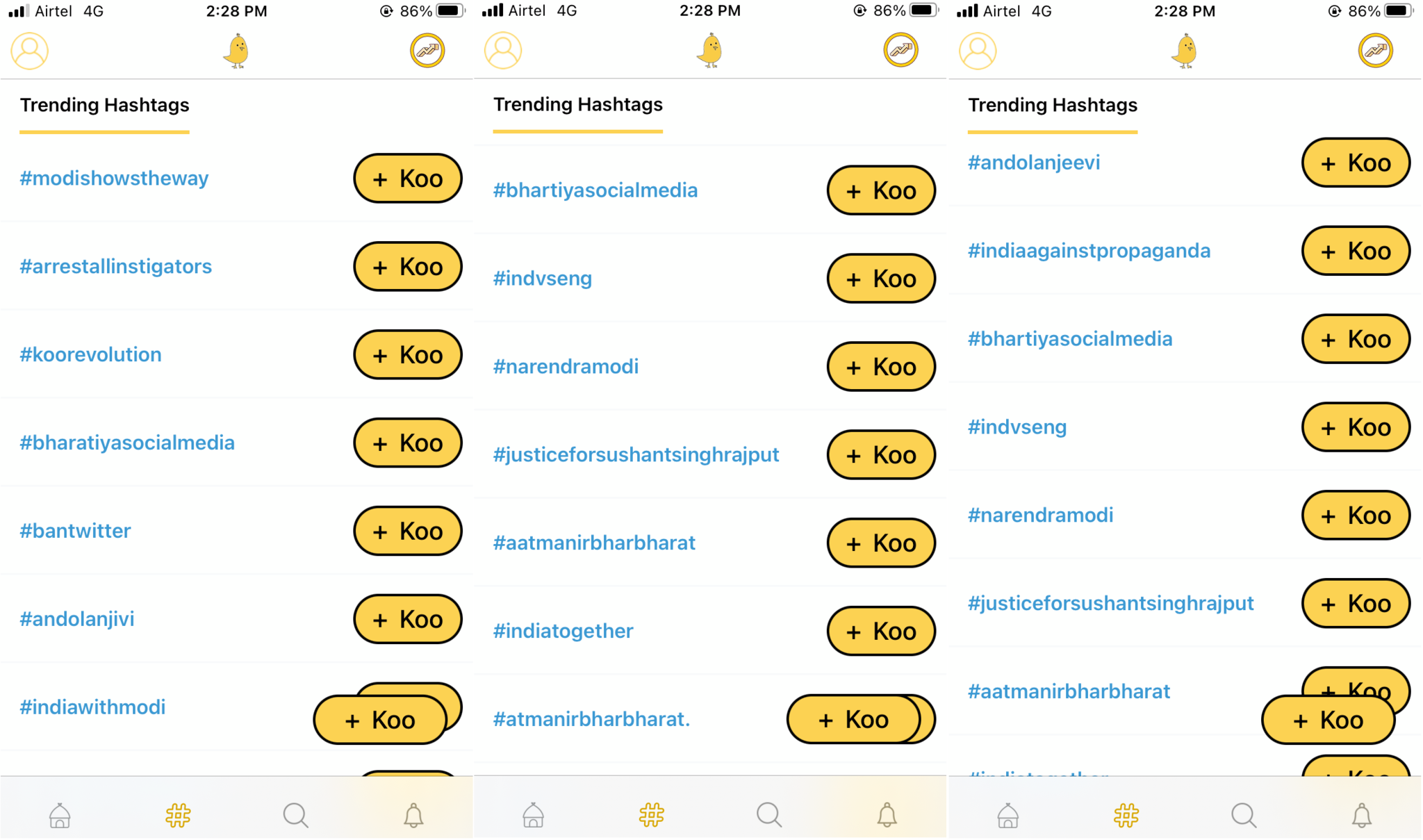

As of now, it appears that Koo’s approach to content moderation is reactive rather than proactive. For instance, Forbes India pointed out to Radhakrishna that #justiceforsushantsinghrajput was trending on Koo on February 10, eight months after the issue started. But Radhakrishna sees no reason to look into it. “We haven’t received any complaints on that yet. If we do, we will figure it out. We are working with teams, consultants, lawyers, everybody right now to make sure that we are moving in the right direction on how to handle all of this."

However, Radhakrishna said, “I am not saying we will have a take as you go. Of course we will do a very quick learning of what has happened across the world and apply it in Indian context. We are working with consultants, lawyers, everybody to make sure we are covered. That’s basically being taken care of right now. You will see over the next one month that we will become a lot more robust," he said. In a subsequent conversation, he revised it to next few days.

Unlike Twitter, users cannot report trending hashtags as harmful. But in a good move, trends are not personalised to the user. Instead, they are determined by what is objectively trending within a language community. “You enter a community, you will see a different set of hashtags," Radhakrishna said.

But Koo has not foreseen the problem of “copypasta", that is, when the same text is copied across multiple posts to inorganically make a topic trend. In August 2020, Twitter finally announced that it would reduce the visibility of tweets guilty of “copypasta". This is part of the reason why now when there is coordinated activity across Twitter, users tend to slightly modify the tweet so that the visibility is not compromised.

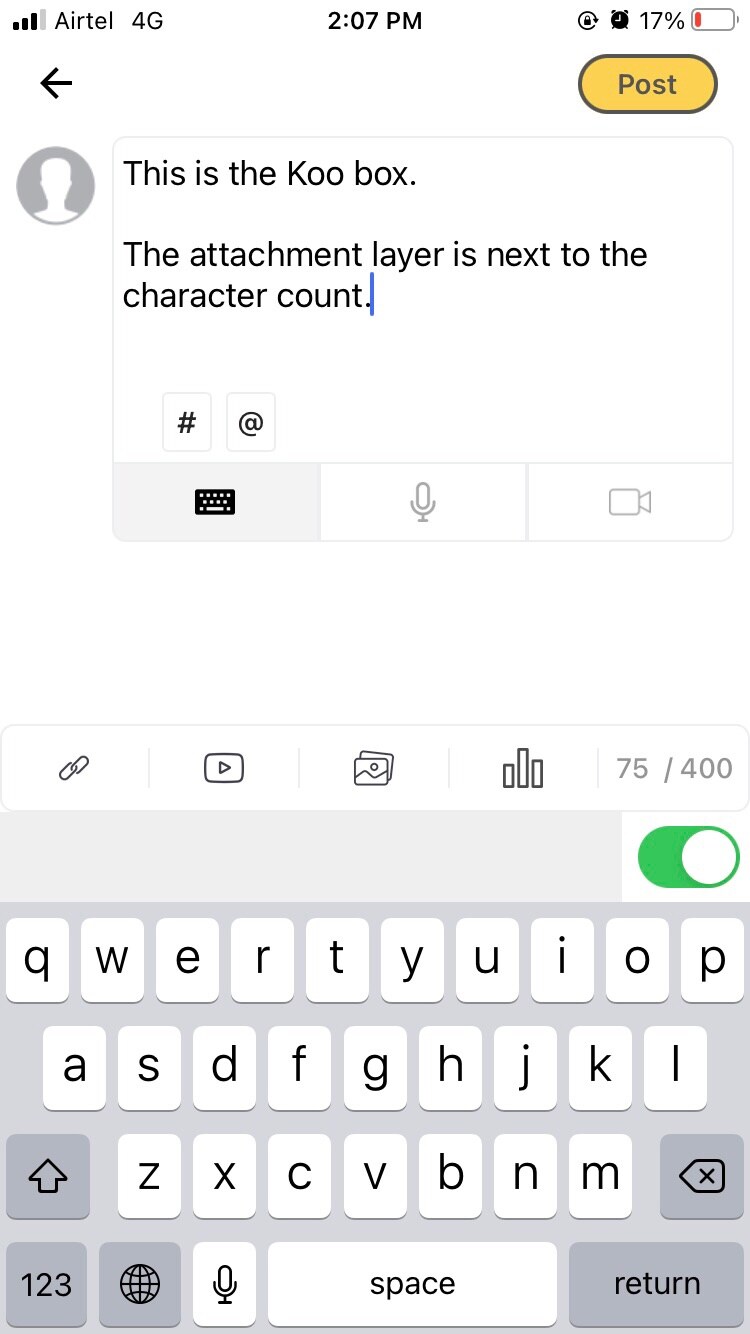

Radhakrishna agreed. “That’s a valid point. We will definitely have some logic to make sure that everybody has an original thought around which they are talking. For example, in our app, even today, there are two parts when you try to create a Koo. There is a box on top and there’s an attachment layer. The box on top is compulsory. No social media app has made the box on top compulsory. We made it compulsory to get you to say something. That is a step in the right direction, saying share your thoughts. We haven’t faced something like copypasta, but if we do face it, we will definitely come up with mechanisms to stop it," he said.

Twitter had implemented a similar move. Ahead of the US presidential elections in 2020, Twitter had temporarily made it impossible to retweet/quote tweets without the retweeter adding some text. This was done to prevent passive amplification of content in a highly polarised political environment.

Koo also focusses on automatically “adding value" in terms of content for the user. “If someone comments on your Koo saying ‘hi’ and that hasn’t added too much value to your Koo, we don’t add that to the feed. It gets pushed away because the content creator wants comments that add value to the conversation. So those kinds of technologies we have developed," Radhakrishna said.

On telling him about a set of Koos from different users that had similar kind of content (see below), Radhakrishna said, “We will handle all of this. As a short answer, yes, if it starts causing trouble overall, we will definitely handle all of this. We are learning on the job with microblogging. Twitter is a decade and a half old company and in 10 months, I think we have come quite far. All the questions you are asking are valid and I would love to talk to you and make sure we have covered everything while we are making ourselves robust. All I can assure you is that our intent is in the right place and we will build the right thing for India," he said.

Is Koo the Parler of India?

Until February 11, on logging into Koo on the mobile app, the top recommendation for an account to follow was news channel Republic. Three accounts later, Koo listed the IT Ministry’s account. Since the publication of an article by The Print’s about this, the list has changed to recommend Amit Malviya, the head of Bharatiya Janata Party’s IT Cell and actor Anupam Kher. On the Hindi web version of the app, Republic Bharat is still the top recommendation, ahead of IT Minister Ravi Shankar Prasad.

In January 2021, Republic entered into “editorial partnerships" with Koo and Mitron, another Indian app. “They are using Koo to get reactions from their viewers. No other media partner is doing that for us today. Once more media partners sign up, we will start showing them also. These guys are showing, ‘Debate on Koo’. It becomes a nice cycle. People who watch it there want to follow that channel," Radhakrishna says of the partnership.

Radhakrishna explained how the recommended accounts work: This list is dynamic and is currently based on a user score of the recommended accounts which is calculated on the basis of the account’s activity and like percentage. “If you have great activity on the platform and you are engaging your users, you get a higher score," Radhakrishna said. As of now, they are not personalised for the user viewing but Koo is moving towards it.

Algorithmic personalisation worsens the echo chambers on social media. The Kiwi government’s 792-page report on the Christchurch mosque shooting—that was livestreamed on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Instagram—concluded that the shooter was radicalised on YouTube. Other research has also shown that personalisation of content on social media leads people down rabbit holes, inevitably radicalising them.

Most Koos right now have the exact same set of hashtags:—#modistrikesback, #bantwitter, #bharatiyasocialnetwork, #atmanirbharbharat, #indiawithmodi, #andolanjivi, #jaihind. Radhakrishna laughed on being told of the entire list.

Koo’s popularity has been bolstered by Twitter’s refusal to block access to accounts of journalists and activists in India. In response, many commentators have levied charges of anti-nationalism and bias against Twitter. Users have made public proclamations (ironically on Twitter) about leaving Twitter to join Koo in a display of nationalistic pride.

The American app Parler gained prominence in 2020 when Twitter added fact-checking labels to the then US President Donald Trump’s tweets. A number of conservative, right-wing commentators and users migrated to Parler. However, given the platform’s refusal to take down content that ultimately led to the violent insurrection at the Capitol on January 6, 2021, a number of third party service providers such as Amazon Web Services, deplatformed Parler.

Radhakrishna disagreed with the analogy. “The context with which each app gets traction is very different. It’s not like we are in America and there was a US presidential election and there was, that’s not the context. The context here is very different and we have been building this, we launched it 10 months ago, but we have been building it since November 2019. And all of this has come together for us serendipitously. If we knew this was going to happen, we would have been more prepared with our servers and all and I would have built a larger team by now. I think our context of getting Indians excited about Koo is very different from what excited users on Parler in the US," he said.

Will the move to Koo stick?

This is not the first migration of Indian users from Twitter. The first one took place for the exact opposite reasons.

In 2019, Twitter suspended Senior Advocate Sanjay Hegde’s account twice for violating Twitter’s policy— first on October 26 for sharing a picture of German worker August Landmesser, who refused to do a Nazi salute at a rally, and then on October 27 for tweeting a poem titled “Hang him" by Gorakh Pandey. The account is still banned on Twitter. A number of prominent Indian journalists, activists and writers consequently accused Twitter of bias and not shielding Indian activists from abuse. They announced (again on Twitter) that they would join Mastodon, a free, open-source ad-free decentralised platform where users can use their own servers (“instances") with their own content moderation rules.

In the two years since, most of these Mastodon accounts have not seen much activity. And the reason is quite simple. Social media platforms rely on social graphs and networks. Porting your entire social network from one platform to another is practically impossible. Reaching that critical mass of influence on a new social media platform which is identical to the old one, as Mastodon and Koo are, is rare, if not entirely unprecedented. But Koo has a unique advantage because of its focus on local Indian languages, 12 of which are “coming soon".

Koo’s local advantage

Koo’s much bigger and better resourced rivals have struggled over the years to moderate content in non-Western territories as they do not understand the context. Facebook, YouTube and Twitter usually contract out content moderation to third-party vendors such as Cognizant, Genpact, Accenture, Majorel and Competence Call Center in the Philippines, India, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, Germany, Latvia and Kenya. The content moderators have to sift through some of the most dreadful content online, including but not limited to violence, child sexual abuse material, and terrorism.

According to a 2020 report from the New York University, most Silicon Valley companies do not hire enough content moderators who understand local languages and cultures because of which their platforms have been used to stoke ethnic and religious violence, such as in Myanmar and Ethiopia.

This is where Koo has a massive advantage—local context.

Currently available in six languages—English, Hindi, Kannada, Tamil, Telugu and Marathi—, Koo has a team of community managers, its terms for content moderators, for each of them. Each content moderator is well versed with the local context and language as they are all locals of the community.

The platform has recruited eight people to moderate content in English and is going to scale up further. Bangla, which is only available in beta, and is at an invite-only stage right now and not been opened to the larger audience yet, already has “two Bangla girls working on it". Radhakrishna refused to provide details of the sizes of the content moderation teams in other languages citing competition as a reason.

It is not the first time Radhakrishna and Bidawatka have dealt with content in Indian languages. Their first venture together—Vokal, an information sharing platform which they describe as “Quora with audio"—is also available in 11 Indian languages wherein subject matter experts answer people’s questions. While the two are separate products, Bidawatka admitted that an algorithm that was used to decide people’s ranking on Vokal has made its way to Koo. “There are certain elements that are used but it is very minimal," he said. Some teams are common between the two companies.

“Vokal is running as a self-sustained engine right now. We aren’t spending time on it because we have spent a few years on it and it’s a running engine. So as and when some requirement is there, someone will look into it," Bidawatka said.

Like Koo, it also does not generate revenue yet. “We should get a certain scale and I think we will open up a. premium version, an ad model. So advertising should be one of the ways to monetise," Bidawatka said, talking about both Vokal and Koo.

How secure is the platform?

Baptiste Robert, a French cybersecurity expert better known via his Mr Robot inspired nom de plume Elliot Alderson, sparked off a flurry of activity when he tweeted that the app was leaking the personal data of users.

Radhakrishna conceded that the app was leaking details of users’ emails but clarified that only 3-4 percent of the users use email addresses to log in. Logging in via email is an option only available to Android users and was introduced in late 2020 at the request of users. The issue, he said, has since been fixed.

On Robert’s allegations that the app is also leaking users’ dates of birth, gender, and marital status, both Radhakrishna and Bidawatka maintained that these are details users choose to enter in their profiles and make public anyway. “I don’t know how that is a leak," Bidawatka said. As of now, there is no way to make a Koo profile private only the phone number can be made private.

However, in a subsequent tweet, Robert said that the data leak was based on information that the user had not made public. “[W]hen I used the mobile application, I was looking at the network communication made by the application, I was able to get a lot of personal information about the user. I was able to get date of birth, marital status, gender and email. And this kind of information is not shown at all in the profile view. This is a fact," Baptiste said.

Forbes India can confirm that the personal details Robert had mentioned were not publicly visible on the verified profile in question, of one Sonal Goel, both on February 10 and on February 12.

At Forbes India’s request, Robert checked the network communication on February 12, using the same methodology that he had used on February 10. He discovered that date of birth and marital status were no longer being leaked but gender still was. Email address, as the founders had already admitted, had already been removed. “They fixed everything then," Robert said. Forbes India reached out to the founders repeatedly via calls, messages and emails but did not get a response.

Koo, unlike most other social media platforms, does not have passwords and only relies on phone number-based OTPs. Citing the case of WhatsApp, Radhakrishna said that OTPs are safer than passwords. “We don’t see the need for a password because we use phone number-based OTP as most of India has a phone number and not email address," he said.

A cybersecurity expert who specialises in mobile app security told Forbes India on the condition of anonymity that relying only on OTP-based log-in is not secure. “There are multiple issues that can occur. If someone has your device, or someone intercepts the message with the OTP, or the third-party generating OTPs gets compromised, there is no other protection for the account."

“For a social media platform, you would want to have multi-factor authentication," Yash Kadakia, the founder and CTO of cybersecurity firm Security Brigade, told Forbes India. Radhakrishna agreed that two-factor authentication (2FA) is safer than just OTP. “We will move to that. We haven’t enabled it yet." But he disagreed on whether it was necessary for a social site.

“A big advantage of not having passwords is that the company does not have to secure a database of passwords, and it’s less susceptible to attacks aimed at compromising that. Having said that, only OTP-based login is not secure," the expert said. Another advantage is that it precludes the risks associated with password reuse, that is, where the same password is used across multiple platforms, Kadakia said.

“Ideally, factors of authentication should flow from what you know, which is the password what you have, which is the token [OTP or app authenticator] and who you are, which is biometric or some other technical parameter, which is extremely standard," the first expert said.

Kadakia also warned that a bigger problem than OTPs is unauthenticated backend dashboards or APIs that hackers look to exploit. “Both OTPs and passwords are a level of authentication that an attacker has to bypass," he said.

Another issue with the app on an iOS device is that after signing out, when a user signs in again, it does not generate a new OTP or re-authenticate the user. “That would typically be flagged as a security issue because that means they are technically not signing you out. That’s a pretty straightforward problem. If you are on an office device or a public device, if you sign out, it should sign you out. If it lets you sign back in without any authentication, that’s obviously a problem," Kadakia said.

A Chinese connection

Serial entrepreneurs and investors Radhakrishna and Mayank Bidawatka started developing the app in November 2019 and launched it in March 2020.

Last week, Koo raised $4.1 million as part of its Series A funding, YourStory reported. Investors included Infosys alum Mohandas Pai’s 3one4 Capital, Accel Partners, Kalaari Capital, Blume Ventures, and Dream Incubator. According to a PTI report, BookMyShow CEO Ashish Hemrajani and Zerodha’s Nikhil Kamath are also going to invest in Koo.

Radhakrishna had earlier founded TaxiForSure that he sold to Ola in 2015. Bidawatka, who helped grow TaxiForSure and was a core team member of redBus, has invested in Vogo Automotive, Yolo Bus and Third Wave Coffee Roasters among other companies. In 2017, he and Radhakrishna co-founded Vokal.

On February 10, Radhakrishna told CNBC TV18 that their earlier venture, Vokal, had a Chinese investor Shunwei Capital who was a very small stakeholder and was on its way out. “Shunwei was an investor two-and-a-half-years back and they came in way before the government had a ban on Chinese funds or apps," Bidawatka told Forbes India. He said that given their huge investments in content start-ups, they raised funds from them when they were working on Vokal.

“But they [Shunwei Capital] also understand the government’s stance on Chinese money and involvement. And hence, their stake will be bought out. We are anyways an Indian company registered in India," Bidawatka said.

Founded by Xiaomi founders Lei Jun and Tuck Lye Koh in 2011, Shunwei Capital had, as of April 2020, invested in nearly 400 companies and manages $3 billion of assets. It has invested in a number of Indian start-ups over the years including ShareChat, Zomato, Rapido, MyUpchar, Kuku FM, LoanTap, Truebil, Pratilipi, Mech Mocha, Cipapp, Upwards, Sim Sim, Krazy Bee, Cashify, Rozzbuzz, Chalo and Meesho.

On June 29, 2020, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) had banned 59 apps (a number that would rise to 267 by the end of 2020), all from Chinese companies, citing national security reasons. Less than a week later, NITI Aayog had launched the Digital India Aatmanirbhar Bharat App Innovation Challenge wherein the government would select the best Indian apps in different categories and help them scale and provide them with financial incentives. “The Mantra is to Make in India for India and the World," the press statement for the challenge had read.

Koo had been adjudged the second-best social app along with YourQuote, a creative writing app, while a TikTok alternative, Chingari, had won in the category. TikTok was one of the apps that had been banned a week earlier by MeitY.

Update (June 2, 2021 11:53 am): Since this story was published, the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021 were notified on February 25, 2021. According to TechCrunch, Koo had 6.5 million active users in April. As a result, Koo became a significant social media intermediary and had to carry out additional due diligence. Radhakrishna confirmed to Forbes India that the microblogging website was in complete compliance with the Rules. It has now published Community Guidelines, in line with the contours laid down in Rule 3, listed contact details for its Chief Compliance Officer and Nodal Contact Officer, and name and email address for the Resident Grievance Officer. It is not clear if the platform will start publishing monthly transparency reports as well, as is required of significant social media intermediaries.

First Published: Feb 12, 2021, 18:57

Subscribe Now