The year had already started off on the wrong foot for Swarup Ghosh. The founder of non-profit Tomorrow’s Foundation in West Bengal, which works in primary education for marginalised children and skill development for young adults from vulnerable backgrounds, had to lay off five people shortly after the national lockdowns. A large software company had pulled out funding for an in-school programme for children, as the money was being redirected to PM-Cares and Covid-19 relief work.

As Ghosh began requesting corporate donors to at least provide enough funding to cover staff salaries and dipped into the contingency funds, another major setback caught him off-guard last week. On September 21, the Lok Sabha passed the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment (FCRA) Bill 2020, which redefined terms for how non-governmental organisations (NGOs) can accept, transfer and utilise foreign donations and contributions. It was ratified by the Rajya Sabha on September 23 and the gazette notification was out on September 30.

Ghosh is already thinking about ways to re-calibrate operations in ways that will cause minimum damage. “About 40 percent of our funds come through large FCRA-registered donors, including Save the Children, the United Nations Children"s Fund (UNICEF) and The Hans Foundation,” he says. The funding shortfall might result in about 25 percent of team members facing salary cuts or layoffs, and about a scaling down of about 40 percent of projects currently running in West Bengal, Chhattisgarh and the North-East. “Right now, everyone is just confused as to how this Act will finally be implemented. I understand there is a need to ensure transparency and stop misuse of foreign funds, but this way, even organisations doing good work are getting impacted.”

![fcra_1 fcra_1]() Stricter over time

Stricter over time

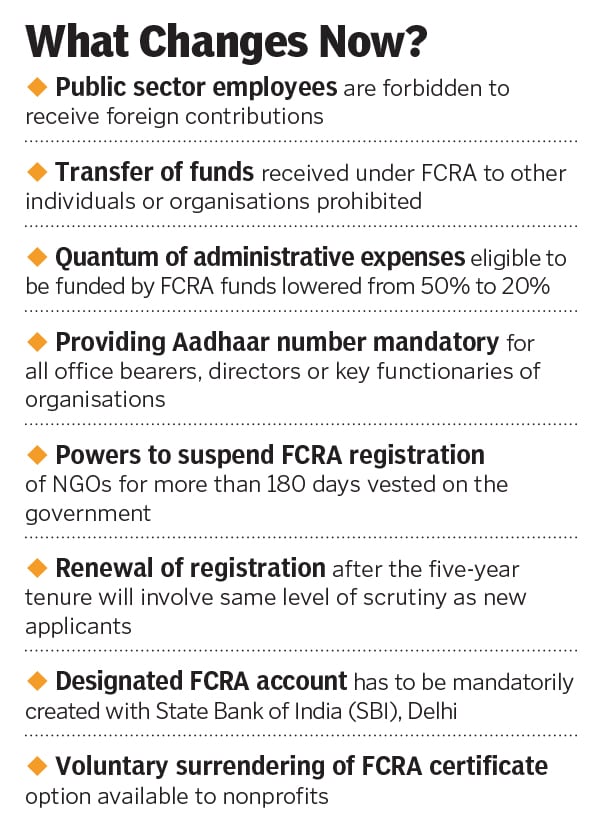

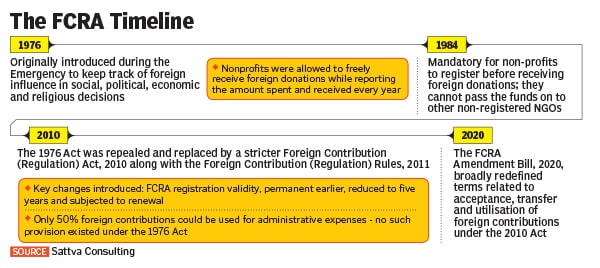

The history of the FCRA in India has been rather contentious. It was an Emergency-era legislation originally implemented in 1976 to keep check on foreign influence in the social, political, religious and economic fabric of India. The 1976 legislation was subsequently repealed in 2010 to create a more stringent law, which, among other changes, reduced the permanent validity of an FCRA registration to a period of five years, followed by a renewal process—and mandated that only 50 percent of foreign contributions could be utilised for administrative expenses.

The 2020 Amendments to the FCRA tighten the noose around civil society organisations further, with provisions that prohibit ‘re-granting’ or the transfer of foreign funds from one organisation to another, reduce the cap on FCRA funds for administrative purposes to 20 percent [from 50 percent earlier] and make it mandatory for all office bearers, directors or key functionaries of NGOs to furnish their Aadhar details, among others changes

![fcra_2 fcra_2]()

As the Bill was being passed in the Lok Sabha, Minister of State for Home, Nityanand Rai [who had introduced the Bill on behalf of Union Home minister Amit Shah], stated that the government’s intention was to bring about “greater transparency and stop misuse of foreign contributions by some people”. He said a legislation of this nature is required for the government’s vision of an Atmanirbhar Bharat and to make sure the funds are spent in the right direction and for the right causes.

In Parliament, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) MPs also alleged that this foreign money was being used for religious conversions. While clarifying that the Bill was not against religious minorities and communities, Rai said, “FCRA is a national and internal security law to ensure that foreign funds do not affect national interests. Many, in the past, have hurt the nation’s cultural, internal and democratic security, and to protect them is our prime concern.”

Stakeholders in the development sector say that while they welcome regulations to ensure transparency, the regulations in their current form would make it exceedingly difficult for many nonprofits, particularly the smaller organisations in remote and rural areas, to meet eligibility criteria and ensure compliance. The development sector, experts say, is one of the largest employers in the country, and the regulations could add to the job loss burden.

“The government is not wrong in saying they need to know what exactly is happening with funds, but like in the case of the Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) norms for businesses, the norms need to be simplified,” says Vrunda Bansode, head of India Data Insights at Sattva Consulting, a social enterprise working with non-profits and corporates to implement projects in the social sector. “While the government feels the need for stricter regulations, they must also be aware that enough good has been done with this money. So, if ease of doing business is important for development, so is ease of doing philanthropy.”

Some hits, most misses

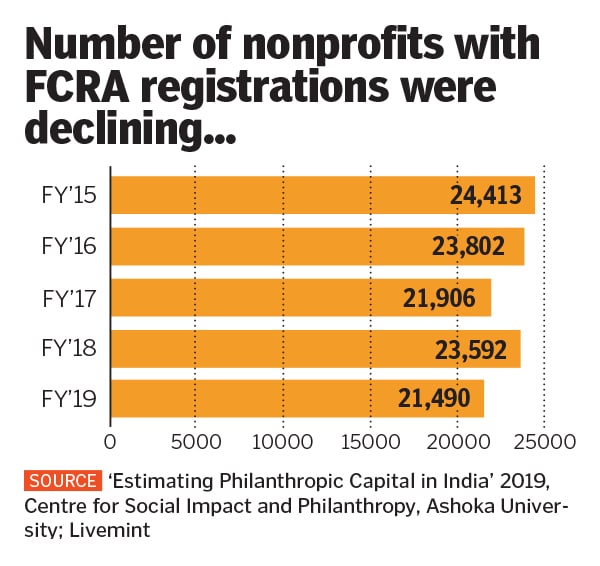

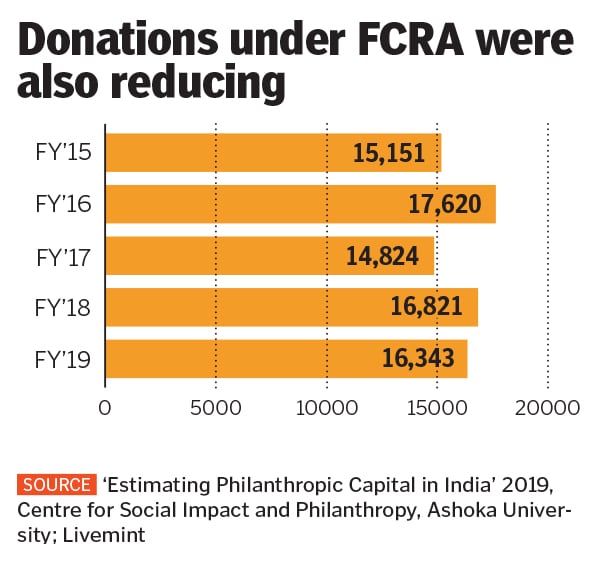

Founders of non-profits say that two key provisions in the amendments are likely to create the most devastating impacts to the core of the sector: The foremost being the regulation that prohibits re-granting or transfer of FCRA funds from one organisation to another. Out of the 400,000-odd registered non-profits filing for tax exemptions in India, only a little over 21,000 are registered under FCRA. A 2019 report titled ‘Estimating Philanthropic Capital in India’ by the Centre for Social Impact and Philanthropy by Ashoka University indicates that nearly 90 percent of these FCRA-registered non-profits do not receive big foreign funds.

![fcra_5 fcra_5]()

“More than 90 percent of these 20,000-odd non-profits [registered under the FCRA] receive a grant size of less than Rs1 crore. By increasing the regulatory barriers around these small non-profits, the policy is channelling limited state capacity on a needle search. The ease of doing civic work just regressed back to the License Raj,” says the founder of a Delhi-based non-profit funded by a global impact fund, who did not want to be identified.

Amitabh Behar, CEO of non-profit Oxfam India, explains that the large organisations that receive the most amount of funds work with smaller frontline organisations that have direct inroads to local, vulnerable communities. Each of them, Behar says, would get smaller grants to the tune of Rs10 or Rs20 crore to work on various social causes. “About 50 to 60 percent of the total funds received by these small organisations come from larger entities like us. They will almost be shut down.”

Behar, whose organisation has partnerships with about 60-80 such small NGOs, says that the latter do not have the capacity to front-face foreign donors. Plus, most big donors give money only where there is scale. “For a donor, time and resources spent working on a $20,000 grant is the same as a $1 million grant. So they will look for NGOs whose annual operating budgets in the last three years are more than a crore. That itself will eliminate 70 percent of non-profits,” he says. “There will be a disconnect between small entities and those sitting on money.”

He adds that he cannot understand the logic behind this provision. “The smaller NGOs to which money is being re-granted also have FCRA certifications, and were already under the scrutiny of the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA). So how does stopping re-granting help anything?”

Bansode points out that instead of stopping re-granting mechanisms altogether, the government had various digital routes to ensure compliance and transparency in the flow of funds. “Just like income tax administration, which uses digitised processes of scrutiny and audits, the use of digital tools could have made compliance easier for the NGOs, and helped the government track the flow of funds from origin to destination no matter how many layers there are in between.”

![fcra_4 fcra_4]()

Her colleague Aarti Mohan, co-founder of Sattva, says that a demand for additional compliance will have to be backed up with more resources and support systems for non-profits, just like businesses and startups have organisations like Nasscom and Assocham. “Structurally, the NGO sector has not had a chance to have a unified or consolidated representation. No representation, no voices in solidarity,” she says.

According to her, the next big challenge apart from re-granting restrictions, is that only 20 percent of FCRA funds can be used for administration expenses. She says that while service organisations who do a lot of fieldwork [like orphanages, those working on watershed or violence against women, for example] have many other expenditure heads, for NGOs like think-tanks, research, advocacy or tech-based nonprofits, “almost entire operations is human resource-driven. So there is no way to show 80 percent ‘fieldwork’ and 20 percent ‘salaries’. Almost all those sub-heads have to be looked at and reconsidered”.

Behar believes that the 20 percent cap will completely change the nature of advocacy and human resource-intensive work that is being done by many research organisations and think-tanks, like the Centre for Policy Research (CPR) and the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability, to name a few. “It seems like an attempt to limit advocacy or research work that challenges the government,” he says.

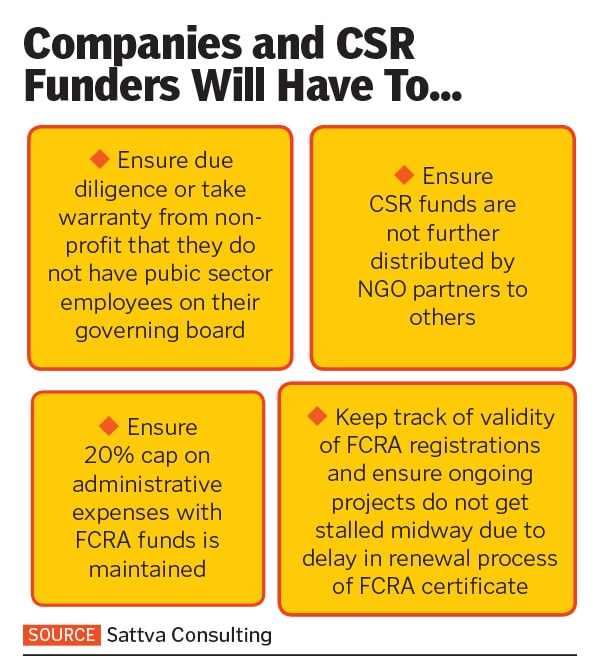

While the FCRA amendment could impede the collaborative, multi-stakeholder approach adopted by the development sector, it will also increase the burden of due-diligence on corporates who work with non-profit organisations as part of their Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), says Mohan. “Additional checks have to be conducted during financial audits. Companies who have multi-year interventions structured in a manner where multiple partners had a different role to executive, will have to make new contracts and figure out ways to keep the projects going,” she explains, adding that making Aadhaar card mandatory might cause pushback on the grounds of privacy and other grounds.

![fcra_3 fcra_3]()

Right now, there is just “chaos” in the development sector as the rules have not yet been enforced, and there is no clarity on how organisations need to proceed. “Can I continue transacting with my existing bank accounts or do I need to open an FCRA account in the State Bank of India (SBI), Delhi, right away? For me, this is no different from demonetisation. We have to pause ongoing programmes and everything is coming to a standstill.”

Bansode draws parallels with the business ecosystem and says that many Indian startups or companies that faced regulatory hurdles in India, chose to get incorporated out of the country even though they have operations here. “The danger is that we might see similar convoluted solutions come up to solve these issues [in the development sector]. There is no denying that there is a need for capital in the social sector, and if there are hurdles, people will find ways to circumvent them, not always leading to the desirable outcome of better compliance,” she says. “Therefore, ease of doing philanthropy needs to be looked at seriously because people really want to comply and do good.”"‹

The Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2020, tightens the noose around the social sector with respect to compliance processes. Representative Image: Frédéric Soltan/Corbis via Getty Images

The Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Amendment Bill, 2020, tightens the noose around the social sector with respect to compliance processes. Representative Image: Frédéric Soltan/Corbis via Getty Images Stricter over time

Stricter over time