How Schoolnet is ensuring India's poorest children don't fall further behind

With its online learning platform designed for rural areas with no internet connectivity, the company is improving learning outcomes with new-age interventions

Gungun Kumari lives in one of the poorest neighbourhoods in Jharkhand’s Bokaro district. Her parents own a small shop selling daily rations. One would assume the free state school she goes to nearby is ridden with absent teachers, a lack of incentives and low standards. Instead, Rajendra High School stands apart.

A tall, rusted gate gives way to an expansive grassy turf around which the school’s classrooms are built. Inside one classroom, Sanjay Kumar is teaching his students about concave and convex mirrors. A rectangular device sits atop his table. Think of it as a mini computer with content rolled into it. The computer doubles up as a projector with speakers, beaming content on to the classroom’s pale white wall, converting it into smart wall. Kumar pulls out a pen from his kurta pocket, taps on a drawing tool on the projection and sketches out the mechanism he is trying to explain to his pupils. He talks animatedly, asks his pupils questions, and challenges them with follow-up questions when they answer. His enthusiasm for teaching—and the pride he takes in it—is as refreshing as the green turf outside, visible through the classroom windows.

“Typically, in a classroom, what do you have is a separate laptop, separate projector and separate speakers. Here everything is embedded into one small box. You don’t even need the internet to operate it. An electricity connection is all you need, and the class becomes a smart class," he later tells us.

“We all wait for our turn to learn using this device," beams Kumari, 15. The school has one such device which it rotates between different grades. Designed for rural areas with little or no internet connectivity, this all-in-one 4kg plug-and-play device is called KYAN, where K stands for knowledge, and Yan refers to vehicle in Sanskrit. Back in the mid-1990s, Schoolnet India, which was then part of the IL&FS group, approached IIT-Bombay to develop such a device that could be used to up the quality of education in government schools. Since then, KYAN has gone through many iterations. As has Schoolnet.

When IL&FS went bankrupt in 2018, it sold Schoolnet, which largely catered to government schools, to Delhi-based Falafal Technologies Pvt. Ltd. Under its new owner, Schoolnet continued its work of improving educational outcomes in India’s most impoverished schools. Today, over 40,000 government and affordable private schools use K-Yan 15 million students and one million teachers like Kumar have been impacted.

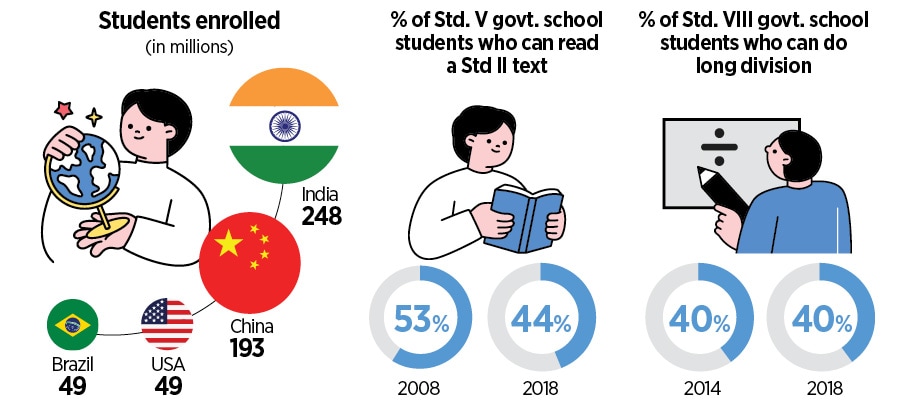

Two-thirds of India’s 1.4 billion people are under the age of 35. It’s what economists refer to as the country’s “demographic dividend".

The Right to Education Act, passed in 2010, requires that all children aged six to 14 attend school but pays little attention to what they learn when they are there. The Annual Status of Education Report 2022, carried out in rural areas by the NGO Pratham, reveals that although school enrollment was high at 98.4 percent in 2022, compared to 97.2 percent in 2018, learning outcomes have remained subpar. Only 20.5 percent of Class 3 children could read a Class 2 text, compared to 27.3 percent in 2018. A mere 25.9 percent of Class 3 students could do subtraction in 2022, compared to 28.2 percent in 2018.

“The learning crisis is serious. Covid-19 exacerbated it," says RCM Reddy, a former IAS officer and CEO of Schoolnet. “Unless we equip our demographic dividend with fundamental foundational skills like numeracy, literacy and problem solving, there is a danger of the dividend becoming a disaster."

To that end, Schoolnet works in the areas of education, employability, and employment— “the 3Es" as Reddy puts it. On the education front, Schoolnet works with government and private affordable schools. On the employability front, it has set up learning centres across the country to impart vocational skills to school dropouts. On the employment front, it helps build public-private partnerships in labour-intensive sectors like textile manufacturing in which it places trained candidates.

It"s been 25 years since Schoolnet started out in 1997. Yet Reddy says the work has only just begun. “If and only if we work on the 3E Agenda, will our human development indicators improve," he says.

Unlike other edtech companies that are reeling in losses, Schoolnet recorded Rs431 crore in total revenue and Rs7 crore in profit after tax in FY21, up from Rs425 crore in revenue and a loss of Rs150 crore in FY20, according to Venture Intelligence (VI). Schoolnet says it posted revenue of Rs475 crore in FY23 with an EBITDA margin of 12 percent. It chose not to share further details and the data was unavailable with VI.

And, unlike other edtech companies that focus on the after-school market, Schoolnet works with, and not against, schools and school teachers.

“The DNA of the company is different," says Raghavan Srinivasan, former editor of The Hindu BusinessLine and a long-time observer of Schoolnet’s work. “They essentially started as a quasi-government outfit [during the IL&FS days], so there is a strong bottom-of-the-pyramid approach which is not there in any of these so-called edtech companies."

Also read: Lesson Plan: Inside LEAD School"s strategy for quality education in small-town India

Zilla Parishad High School in Gundemadakala, Nellore District, Andhra Pradesh where Schoolnet has provided KYAN, teacher training, multimedia content and change management services since 2016

“Tell the kids that the computer bus has come, and they will all run out of their classrooms," jokes the principal of Balijan-Borjan ME School in Assam’s Tinsukia, a left-behind district some 450 km from Guwahati, the state’s capital. Here, Schoolnet has partnered with OIL India, its funding partner, to set up buses outfitted with laptops to teach schoolchildren computer literacy. The buses travel from village to village, conducting 45-minute lessons in colourfully decorated buses.

“The socio-economic makeup of this area is such that parents cannot afford even a smartphone," he says. The programme, which has been running for 10 years now, has had a massive impact: Students, previously unexposed to computers, have gone on to take up computer engineering degrees, he says. “Their life has changed."

Be it basic computer literacy such as this or detailed Class 1 to Class 12 state board or national board specific lessons that are embedded into KYAN, Schoolnet’s intellectual property is proprietary. “So much knowledge gets internalised over two-plus decades. They really know their users," says Srinivasan. The content also incorporates the latest requirements of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 which recognises learning outcomes and 21st century skills as critical for students.

As a result of knowing their audience so intimately, Schoolnet’s approach and delivery matches the capacity of their students, teachers and the infrastructure. Consider how K-Yan works in remote villages without internet connectivity. Or how Sandeep Shinde, a chemistry teacher at the public Rameshwar Vidyamandir School in Mumbai’s western suburb of Santacruz, breaks down complex topics for his students with astonishing ease. He has his students dishing out on the effect of heat on lead nitrate within minutes, using K-Yan. “Earlier we had to depend on boring textbooks," he says. “Now we can make the classes fun and interactive. We can teach concepts, show them relevant videos and even quiz them. Everything is loaded on to this device," he says proudly, patting the K-Yan box placed atop his frayed wooden desk. School attendance has shot up and academic results have dramatically improved too, says Shinde.

But most important factor that sets Schoolnet apart is the fact that it works with schools and teachers. Unlike Byju’s or Unacademy, for example, which work on the premise that what one is being taught in school isn’t good enough, Schoolnet positions itself as an ally to schools. Its solutions help teachers do their job better so they’re not afraid of using it.

Much of Reddy’s personal background informs his work today. He grew up in Dattalur, an impoverished village in southern Andhra Pradesh, with limited access to electricity. He used to walk three kilometres one way to get to the nearest school. “We didn’t have good teachers, teaching quality was not good…" he ruminates. It developed in him a “burning need" to see that learning outcomes at the bottom and middle of the pyramid are improved.

Reddy completed his 10th standard at the school, speaking just a spattering of English. He then studied civil engineering at a college in his home state and went on to become an IAS officer. He served in Tripura, for 10 years, where again, he witnessed first-hand the “importance of education". He later took voluntary retirement from the IAS and joined IL&FS in 2005 where he saw the importance of public-private partnership models.

His biggest takeaway from the early years of working at IL&FS was, “If you are to address the learning crisis in government schools and affordable private schools, you need to partner with the governments. Unless you build sustainable public-private partnerships you can’t be solving the problem at scale. You will only be doing experiments—it may be good work, but it’ll be very small scale and localised."

Schoolnet relies heavily on partnerships with local governments and schools to advance digital in education. In West Bengal, for example, majority of government schools have been using K-Yan for over 15 years. In Gujarat, the government appointed Schoolnet to develop an online system that tracks the progress of every student in every school who uses G-Shala, an e-learning app it developed in the wake of Covid-19. In Delhi, Schoolnet works with the government-run Kendriya Vidyalayas to strengthen after-school learning with Geneo, a B2C app aimed at after-school learning that Schoolnet launched in 2019.

The same content that is on K-Yan is loaded on to Geneo so students can revise the lessons taught in school at home. “Given the internet availability now, Covid-19 has shown us that it is possible to engage students after school remotely," says Ghosh.

Students enrolled in schools that use K-Yan get access to Geneo through their schools. Others can simply purchase the app on Google’s Playstore for Rs450 a month or Rs5,400 a year. Byju’s and Unacademy, by comparison, charge Rs10,000 per annum on an average. Already 900,000 students use Geneo.

“Working with Schoolnet is a pleasure because they understand the problems we face," says Shilbala Singh, presiding officer, assistant commissioner at Kendriya Vidyalaya Schools’ regional office in New Delhi. “For example, they understand that the parents of our students are mostly drivers or domestic help, and are not able to help their children with their studies. With Geneo, children can revise what is taught in school on their own at home. It really helps."

“Affordability is a key consideration for them," says Srinivasan. K-Yan too costs around Rs100,000 in upfront fees, after which schools pay a nominal annual maintenance fee.

In the case of public schools, the government pays for a large part of what Schoolnet does. Schoolnet bids for contracts following the due process and wins them based on merit, says Ghosh. Singh, for example, considered multiple edtech apps before zeroing in on Geneo.

Affordable private schools pay for Schoolnet services themselves. Sometimes Schoolnet partners with corporates like Google, for example, which has provided tablets to some schools to be shared between two students. Others decide to fund certain programmes like OIL India’s backing of the digital literacy programme conducted in school buses across Assam.

“I describe ourselves as a for-profit social enterprise. Unless you are profitable, you cannot create a sustainable solution," says Reddy. He also describes Schoolnet’s model as B2G2B2C. That is, B2G for its partnerships with governments, B2B given that schools are its clients, and B2C given its foray into the after-school segment with Geneo.

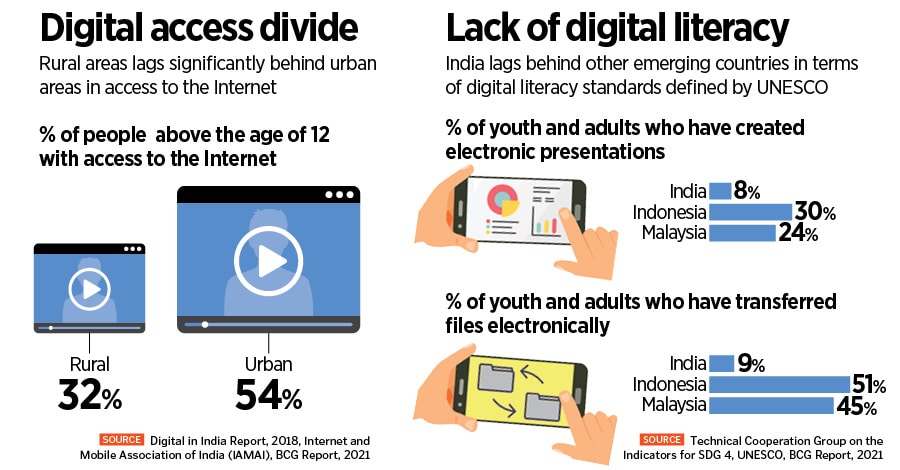

But considerable obstacles exist. In order to leverage digital education"s potential in India the gaping “digital access divide" needs to be addressed, says Rajah Augustinraj, former director, APAC and Middle East, BCG, and primary author of the consultancy’s report on ‘Equipping, Enabling and Advancing Digital Education in India’, 2021. Government schools, especially those in rural areas, lack access to basic infrastructure such as projectors, let alone computers. Besides, internet penetration for people aged 12+ is just 32 percent in rural areas versus 54 percent in urban areas. This naturally hampers the ability to adopt digital in education.

Second, content needs to be relevant, high-quality, and accessible in local languages. A third challenge is the low levels of digital literacy among teachers and students. Only 8.3 percent of Indians aged 12+ have ever created electronic presentations, according to UNESCO. So, teacher training is imperative.

Fourth, digital tools deployed to schools need to serve a wide range of applications/need-states for them to be truly make a difference, says Augustinraj. This includes lesson plans, tests and assessments, and even feedback reports for school administrators. Schoolnet has built a data-driven dashboard that tells school administrators how teachers and students using K-Yan are progressing. Finally, buy-in from central and state governments, school administrators and teachers is key for bringing any change to public schools. “So you see, it is really a multi-dimensional challenge, that requires coordinated, ecosystem-based solutions to drive impact at scale," says Augustinraj.

Schoolnet plans to onboard 245,000 schools, that is, 15 percent of India’s schools and 100 million learners by 2027, accelerating the Right to Education Act and more specifically, the NEP 2020.

To that end, Reddy is a man in a hurry. “A historic opportunity is being presented to us right now for greater adoption of technology in education. If we miss the next five years, the digital divide between the bottom and middle of the pyramid schools and those at the top will further widen and it will be difficult to fill the gap. We will be doing our country a great disservice," he says.

It’s this sense of urgency that will bridge India’s gaping learning divide.

(This is the first of a three-part series)

First Published: Jun 01, 2023, 11:14

Subscribe Now