It’s been a gloomy few weeks in India.

Across cities and towns, a raging second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc and brought its crippled health care sector to its knees. Many states have resorted to lockdowns to restrict movement, as beds, ventilators, and even oxygen supply run short. In April alone, over 30,000 people have died, as daily cases surged from less than 15,000 on March 1, to 3.5 lakh on April 26. That number is expected to swell in the coming weeks, even as questions have been raised about its veracity, with inadequate testing, and underreporting of death in some states.

Amidst all this, the Narendra Modi government is desperately trying to ramp up vaccinations, to bring some reprieve to the situation. Perhaps taking a cue from Israel’s successful vaccination policy, and vaccine hesitancy among many Indians, the government now reckons that vaccinating a wider group as quickly as possible is key to ending the pandemic, even though it had initially envisaged an entirely different vaccination programme. The initial plan was to vaccinate 300 million people, including health care and frontline workers by July, before vaccinating everyone else.

From May 1, some 60 percent of the population will be eligible for vaccinations, even as concerns have been raised about the availability of vaccines. India is undertaking the world’s largest vaccination programme, and only last week extended it to those between the age of 18 and 45, who account for more than 40 percent of the population.

For this, the central government has shifted control of the vaccination programme to state governments and the private sector, which it reckons will help ramp up vaccine coverage. “It would also make pricing, procurement, eligibility and administration of vaccines open and flexible, allowing all stakeholders the flexibility to customise to local needs and dynamics," the government said at the time of announcing the new vaccine policy.

![]()

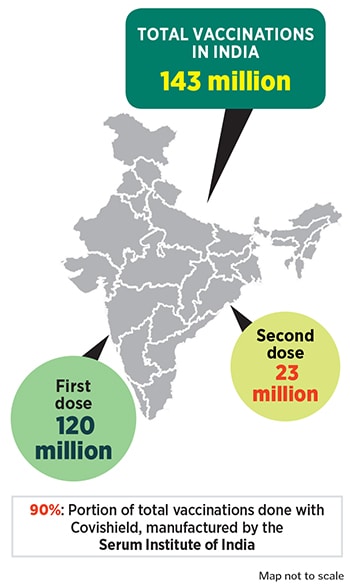

India had begun vaccinations on January 16 and has vaccinated 143 million people. Of these, 23 million have received both doses, while 120 million have received the first dose of either Covishield, manufactured by the Serum Institute of India (SII), or Covaxin, developed by Bharat Biotech.

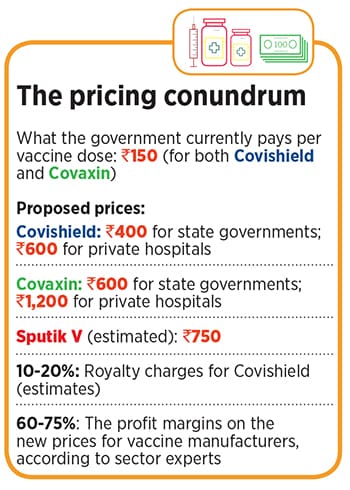

Since the new plan was announced, SII and Bharat Biotech have announced prices for the private sector and state governments: SII will sell Covishield for Rs 400 per dose to state governments and at Rs 600 per dose to private hospitals, while Bharat Biotech has pegged prices at Rs 600 per dose for state governments and Rs 1,200 for private hospitals.

A third vaccine, Russia’s Sputnik V, was approved by India’s drug regulator in mid-April, and its first batch is expected in the country on May 1. While Dr Reddy’s Laboratories, which owns the exclusive marketing and distribution rights to sell it in India, is yet to announce a price, the vaccine is expected to cost less than $10 (Rs 750).

“The price of the vaccine is still lower than a lot of other medical treatment and essentials required to treat Covid-19 and other life-threatening diseases," said Adar Poonawalla, CEO of SII, in a statement after his company drew flak for its pricing, much of which was because the company had been selling the vaccine to the central government for Rs 150 per dose.

Are vaccine manufacturers making money?

SII and Bharat Biotech have drawn flak for the significant difference in their procurement prices for the central government vis-a-vis state governments and private channels. Questions are also being raised about the companies amassing profits amidst a pandemic.

“Considering the economic cost one is paying for Covid-19, there is certainly value at the price at which companies are offering the vaccines," says Vishal Manchanda, research analyst for pharma at Nirmal Bang Institutional Equities Research. “However, the surge in price from Rs 150 to Rs 600 seems a bit exorbitant. $1 or $2 per dose is a price that we do get to see in the vaccine space and doesn"t seem to be off the mark. The huge demand for Covid-19 vaccines allows vaccine producers to operate at a much larger scale than other vaccines they produce, which should significantly help them lower their manufacturing costs per dose."

![]()

The central government, which is doling out vaccines for free, has been purchasing the vaccines at Rs 150 per dose from SII and Bharat Biotech. This means, SII’s rates for the state government and private channels are 166 percent and 300 percent higher respectively, while Bharat Biotech’s prices are 300 percent and 700 percent higher.

Last week, Poonawalla had clarified that SII will soon start selling the vaccines to the central government at Rs 400, once it completes its initial commitment. “Please understand the Rs 150 price which is being thrown around has been for the central government for prior commitments and contracts," he told CNBC TV18. “After that ceases to exist, after we supply about 100 million doses to them, which was ordered in bulk a long time ago, we will also charge Rs 400 to any government." However, on April 24, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare confirmed on Twitter that the procurement cost will continue to be Rs 150.

Over the past week, various state governments have begun negotiations with the vaccine makers. So far, 24 of them have announced that they will be giving the vaccines for free in the state, in line with the central government’s ongoing vaccination programme.

According to Poonawalla’s estimates, the pricing of Rs 150 has been loss-making for him, especially since the company is looking to invest in ramping up production capacity. In January, a fire at an upcoming SII facility also caused damages of Rs 1,000 crore. “We are losing money at the central government"s mandated price of Rs 150 per dose," he told CNBC TV18. “We have to pay 50 percent of the price to AstraZeneca as royalty."

The privately held SII hasn’t disclosed its financial deal with AstraZeneca, which was roped in by the British government to sell the Oxford vaccine. At the time of the deal, a senior official at the company had told Forbes India that the deal involved an upfront payment for selling the vaccine.

“Typically, companies have to pay royalties, and that ranges between 10 and 15 percent," says an analyst with a domestic brokerage in Mumbai. “So it’s unlikely that SII is paying such a hefty amount. Rs 150 is a break-even rate, and when it reaches Rs 600 or Rs 400, it will be highly margin equitable. Their production cost will remain the same, and if you factor in distribution rates, you make around 75 percent of margin at Rs 600." This means a profit of Rs 450 per dose. SII has not responded to a questionnaire from Forbes India in this matter.

“For global vaccine makers such as SII, the Ebidta margin [earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation] on vaccines is between 40 and 50 percent," says another analyst with a domestic brokerage who did not wish to be named. “Those vaccines are priced cheaper, in the range of $1 or $2, like in the case of polio. In this case, with prices on the higher level, and per unit cost being directly related to scale of manufacturing, the Ebidta margin is definitely around 75 percent."

![]()

Other sector experts agree that the royalty costs don’t account for as much as 50 percent. “The royalty that companies typically pay for licensed drugs or vaccines after successful completion of clinical studies is mid to high teens," says Manchanda, and usually doesn’t exceed 20 percent. “Comparing prices to the foreign-made vaccines may not be the right benchmark, as these players have the reputation of being the world"s lowest-cost manufacturer."

Bharat Biotech, which doesn’t need to pay royalty, would have had to invest heavily in research and development (R&D). “Even for Bharat Biotech, they would make similar profits," says the analyst with the Mumbai brokerage. “Unfortunately, since it’s a privately held company, it is difficult to measure the costs, but it is a function of the price. The higher the price, the R&D cost as a factor will be much lower, compared to when it’s sold at Rs 150."

Tushar Manudhane, a pharma sector analyst at Motilal Oswal Financial Services, says India will need 1,200 million vaccine doses to cover the population between 18 and 45 years, with current supplies ranging between 100 and 120 million doses. “The supply is much lower than the demand," he says. “After four-five months, there will be other manufacturers, who will come into play, and that could determine the prices then. While supply constraints may keep prices for private markets at a higher level than for the central government over the near term, one needs to have the capacity to fulfil the demand." This could also influence vaccine prices. “The need to reinvest in additional capacities, royalty payments to innovators, and incremental cost of distribution to private markets may be the pricing drivers," he adds.

Analysts, meanwhile, reckon that manufacturing capacities play a significant role in dictating profit margins. On April 19, Bharat Biotech said it has ramped up its capacity to 700 million doses annually, and received an advance of Rs 1,500 crore from the Indian government.

Currently, it produces about 5 million doses a month. “The question is about how low you can go on your pricing," adds Manchanda. “And that has to do with capacity. Bharat Biotech has already executed their capacity addition. SII already has an advantage with the economies of scale, which means, they can price it cheaper."

Typically, for a manufacturer with the capacity of making 250 million doses a year, a price of Rs 150 will be at a break-even level, or perhaps even a loss. This, without factoring in the cost of capacity expansion that businesses have to bear. “At Rs 150, I am not sure if anybody was making money there are capital investments that an entrepreneur has to recover too," says another analyst at a domestic brokerage. “But, as far as vaccines go, there is a good amount of opportunity available for everyone for the next six to nine months. This is a one-time big opportunity. Whether it is sustainable will depend on the effectiveness of the vaccine. We are shorting mankind, and hopefully that shouldn’t happen."

Making the most of bad times?

Now, as the Covid-19 caseload in India continues to grow, experts suggest the only way forward is to vaccinate as many people as quickly as possible. While most of the states in the country have taken it upon themselves to vaccinate all those above 18 years for free, starting May 1, while flagging the increased cost burdens.

Before the central government announced it new vaccination policy, the states were neither consulted nor given any prior notice about the vaccine procurement policy. For example, on the day the new policy was announced, Tamil Nadu health secretary J Radhakrishnan told Forbes India that he had no idea about the details of the procurement process, and that it might be a “tough call" for states to procure vaccines at higher market prices.

In the Union Budget for FY22, the Centre had earmarked Rs 35,000 crore for Covid-19 vaccinations, and had committed to provide more if required. People above 18 years of age form roughly 60 percent of India’s 138 crore population. So, the number of people eligible for vaccination from May 1 is roughly 83 crore. At the original procurement price point of Rs 150 per dose, the Centre would have had to spend close to Rs 25,000 crore for both doses for the eligible population. However, under the new procurement structure, the Centre will be spending much less, while transferring the cost burden to state governments.

Delhi, which registered over 20,000 cases in the last 24 hours, for instance, has approved a purchase of 13.4 million doses, said Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal on Monday, while appealing to the Centre to lower procurement prices and make it uniform for states and the Centre.

“I believe the price should be the same for everyone," he said, “I was watching the interview of one of the [vaccine] manufacturers who told the interviewer that vaccination companies are profiting even at Rs150, at which they are providing the vaccine to the Central government. If that is the case, then at Rs 400 and Rs 600 their profit margins must be huge. I believe now is not the time to look for profits, now is the time to come together and people and help humanity."

Satyajit Rath, a scientist at the National Institute of Immunology and adjunct professor at the Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, suspects that the current pricing and procurement will create greater uncertainties in the supply schedules of vaccines. “The states are clearly going to face high pricing from the companies, who will promptly claim ‘smaller volumes of orders’ from individual states as the reason why their prices to these states are higher," he says.

That’s perhaps also why states—such as Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh and Punjab—have indicated that they might postpone the May 1 inoculation drive due to constraints in vaccine procurement and availability.

The decision comes at a time when daily mass vaccination numbers are seeing a decline. As per data from the ministry of health, India inoculated close to 3.5 million people in the first 10 days of April, which dropped to 2.8 million over the next 10 days. Up to the week ending April 24, the daily average doses were only 2.68 million. As per targets, if India is aiming to vaccinate its entire adult population of about 83 crore (830 million) with both doses by the end of 2021, the number of average daily doses should increase by at least 2 to 2.5 times.

Prashanth N Srinivas, assistant director (research) at the Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru, believes that vaccination should not be reduced to merely a supply chain issue. “We will not be able to achieve targets in a very predictable manner," he says. “We have to do much more than just involve officials. We have to involve the community, the private sector, NGOs, and really decentralise immunisation."

Srinavas reckons this doesn’t mean liberalising the vaccine strategy, and simply opening it to the private sector. “At the heart of inequalities in public health is markets, so we do not need liberalised vaccine strategies," he says. “You would, in fact, need to govern it further where you push various stakeholders, be it private companies, hospitals or doctors, to ensure equal distribution of vaccines."

Further challenges in mass vaccination are likely to arise because of the significantly higher population among some of the poorer states of India. Nine of the 28 states in India have close to 58 percent of the population. For instance, Bihar, with a population of 10.41 crore (as per Census 2011), has a per capita state domestic product (PCSDP) of Rs 46,664 in 2019-20. Another example is Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, with more than 19 crore people, but a PCSDP of just Rs 65,704. In contrast, Goa has a population of just 14 lakh and a PCSDP of Rs 472,216 while Maharashtra has a population of around 12 crore and a PCSDP of Rs 202,130

“I have no doubt that there is a numerically large but proportionately small minority of affluent people who can and mostly will afford to buy vaccines at these prices, thus fulfilling vaccine makers’ dream of super profits," says Rath, adding that this will create tensions between vaccine supply to price-regulated government sector and the free-pricing private sector, creating inevitable scarcities for the state-provided free vaccination campaigns. “There is no crystal ball needed to estimate that opening up the private market for the same vaccines is going to exacerbate the shortage. However, the shortage will then be particularly acute for the poor, who perhaps have less of a voice of protest that matters to the government." Rath adds that he is also unsure of what the legal status is of a direct private market sale of vaccines that are only provisionally approved with an ‘emergency use authorisation’.

While Srinivas hopes that the government will follow up with stricter norms to prevent distortion of vaccine access by private market mechanisms, Rath says that if a private market has to be created to take pressure off the state-provided vaccination campaign, one way to go about it might be to allow the mRNA-based Covid-19 vaccines like Moderna and Pfizer into the private market, as their usage by the affluent could marginally reduce the pressure of the public vaccination campaign of the state.

“All we can hope for is that more and more vaccines will come into play, and will therefore provide supply sources," Rath says. “However, given the extraordinary silence about the supply of Sputnik V even after its emergency use approval in India, I don’t know how much hope there is in this direction either."

Already, health care companies such as Manipal Healthcare has readied plans to procure all the available vaccines in the market. “While we may have specific preference for some of the corporate customers and could try and plan on that basis, we would also hope to be able to cater to the ask of a choice, if indeed that is feasible," says Dilip Jose, MD and CEO, Manipal Hospitals. “However, all this would be subject to the roll-out plans and supply processes of manufacturers, much of which would only evolve over the next several weeks."

For now, its an uphill battle in India. And, availability of affordable vaccines in the country, where nearly a third of the population lives below poverty line, will be the only way out to fight the pandemic, that has brought the country to its knees in recent days. “Vaccines should be made available not based on who can pay, but based on universal principles," says Srinivas. “Because no one is protected against Covid-19 until we’re all protected and vaccinated."

(With additional inputs from Salil Panchal)