Janhavi was first harassed by her superior at work in late 2019, three months into her job at the India office of a reputed global non-profit organisation.

He repeatedly used sexually coloured remarks during his conversations with her, and made jokes casting aspersions on her character in front of her colleagues. Even though the company has more than 100 people working in India, there was close to no formal recourse available to register a complaint. “The India head was supportive, but simply changed my reporting structure, and I just didn’t know what options were available to me to address this issue,” says Janhavi (name changed), a researcher in her late 20s.

When the India head and the concerned human resources representative left the company, Janhavi’s reporting structure changed again. The harassment continued, even through the lockdown and the pandemic. “While he was careful not to leave email or text trails as we worked from home, he spread rumours that he has had to repeatedly reject my advances, and asked juniors and colleagues to not communicate or collaborate with me. I felt alone and isolated. He also constantly criticised and insulted me with respect to my work,” says Janhavi, who continues to work with the company since her efforts to switch to other career options in the last one year did not materialise. “Taking this up with the global head office also didn’t help because he has a lot of power within the organisation and in the industry.”

While her company finally did set up an internal committee (IC) in accordance with the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013, commonly referred to as the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (PoSH) Act, for Janhavi it seems too little, too late. At the time of writing the story, she is contemplating approaching the women and child development ministry’s complaint portal to register her grievance.

Harassment in the time of Covid-19

On February 17, a Delhi court acquitted journalist Priya Ramani in a criminal defamation lawsuit filed by MJ Akbar, a Rajya Sabha MP, for accusing him of sexual harassment in 1993 when she met the former editor for a job interview. “Woman has [the] right to put her grievance at a platform of her choice even after decades,” the court observed. “Sexual abuse takes away dignity and self-confidence. Right of reputation can’t be protected at the cost of the right to dignity.” Ramani’s testimony, and the judgement, highlighted various aspects of workplace sexual harassment, ranging from how it is not always physical, but also verbal, to the absence of strong institutional redressal mechanisms to support and empower women.

![posh-infographics-1 posh-infographics-1]()

In India, the Vishakha Guidelines to prevent workplace sexual harassment were formulated only in 1997. It was only in 2013, a full 16 years later, that the PoSH Act was enacted. In 2017, the Indian National Bar Association published a report based on a survey conducted among 6,047 professionals across sectors including IT, manufacturing, media, health care, agriculture, non-profits, and automobiles, apart from the unorganised workforce. It indicated that 53 percent respondents faced sexual harassment through their immediate managers. But 69 percent of them did not report the offence due to reasons including fear, no awareness of their rights and a lack of faith in the redressal mechanism.

In 2021, eight years after the PoSH Law was implemented and one year after the Covid-19 pandemic changed the nature of work, there remains much to be desired from this piece of legislation, particularly around creating conducive workplace systems that empower women to speak up, and processes that enable collecting and studying data to understand the extent of implementation.

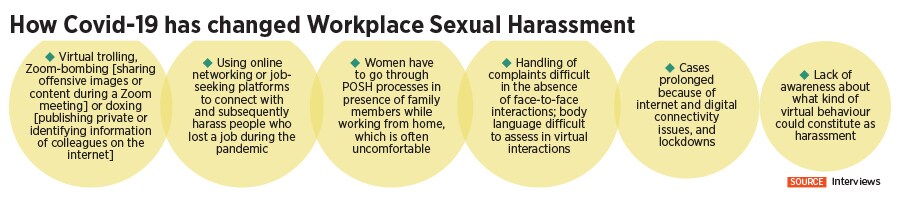

“Things have become much worse during the pandemic,” says Shivangi Prasad, a lawyer who is the founder partner of POSH at Work, a firm that helps organisations comply with the workplace sexual harassment law. Covid-19 threw up challenges for the Internal Compaints Commitees [ICC] of companies that investigate sexual harassment complaints, and for women at the receiving end of abusive behaviour. Prasad says that there have been instances of Zoom-bombing [sharing offensive images or content during a Zoom meeting] and doxing [publishing private or identifying information of colleagues on the internet].

She explains how women who lost their job during this crisis were harassed by people posing on networking and job-seeking platforms as recruiters or high-level employees helping them find a job. Handling complaints in the absence of face-to-face interactions had its own share of difficulties. “Body language is difficult to assess in virtual interactions. We also had situations where people sat for virtual meetings with someone else in the room prompting them, or they were responding after reading something. In one of the cases, people had their lawyers present, even with clear rules that internal committee enquiries are supposed to be conducted without lawyers,” says Prasad.

Two developments crucial to remote working that have emerged during the pandemic are increased virtual communication, and the blurring of personal and professional work timings. Online chat platforms that became pervasive during work from home also led to harassment, says Ishani Roy, founder of Serein, a consultancy firm that works on PoSH training, diversity and inclusion.

“Many women had people commenting on their WhatsApp display photos or how they look. They received uncomfortable messages from colleagues and were forced to have conversations that invaded their privacy,” she says, adding that working remotely also prevented many women from coming forward to report harassment. One of the reasons was that it became very difficult for women to undertake PoSH-related interviews and formalities in the presence of other family members at home. “Enquiries into complaints were also delayed because either people were stuck somewhere due to the lockdown, or there were internet connectivity issues,” Roy says.

With respect to implementation of PoSH guidelines during the pandemic, a two-pronged approach was required, says Aarif Aziz, CHRO, Diageo India. It was important to find creative and engaging ways to tell employees how the concept of the workplace was expanding. “We trained them to understand how a WhatsApp chat between two colleagues could turn into sexual harassment, and what unwelcome behaviours on digital platforms look like. It was important to go beyond policies to increase our sense of awareness,” he explains.

![posh-infographics-2 posh-infographics-2]()

Diageo India has 1,700 professional employees, out of which 21 percent are women. Aziz believes that in the wake of the pandemic, it was important to train the leadership and members of the ICC too. “We had to help them understand how the workplace is changing, what kind of situations related to harassment can come their way, how they can deal with them, how to conduct investigations over digital mediums, what questions they can ask and how they can ask them to get more data and information about the situation.”

Beyond Metros and Formal Sectors: Not a Pretty Picture

While the #MeToo movement and increasing cultural awareness led to companies, especially larger ones, spending more time and effort toward implementing PoSH guidelines, the number of cases reported to ICCs in 2020 are likely to reduce, according to Vishal Kedia, PoSH trainer and founder of Complykaro. “One reason why complaints would have gone down is because many people do now know what could constitute sexual harassment in a virtual space. The complexity and the grey areas are increasing,” he says, adding that the exact number of cases registered by companies will be clearer by June or July, once all companies put out their annual reports for the previous fiscal.

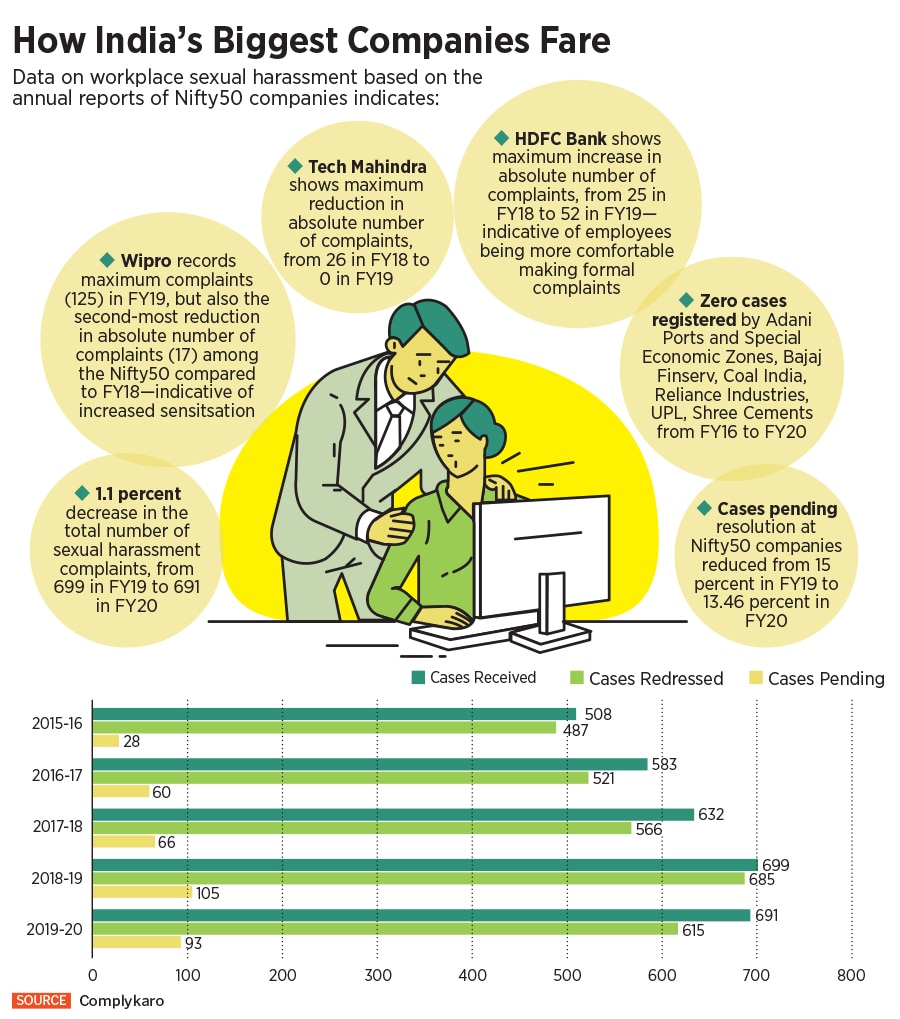

Complykaro, which helps companies follow workplace sexual harassment laws, collates and studies the number of complaints registered every year. According to their data, in FY20, the number of complaints registered at Nifty50 companies reduced to 691 from 699 in FY19. The percentage of cases pending resolution also reduced from 15 percent to 13 percent during the same period.

In FY20, IT company Wipro received the highest number of cases at 125, which is 18 percent of the total number of cases registered by Nifty50 companies. The IT company also saw the second-highest reduction in the number of complaints, reducing from 142 the previous year. According to Complykaro, this indicates higher levels of sensitisation among employees and leaders.

Other companies with a high number of registered complaints include Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) with 86 cases, Infosys with 60 cases, ICICI Bank and HDFC Bank with 52 cases each. Tech Mahindra, which had registered 26 cases in FY19, saw a 100 percent reduction, with zero cases registered in FY20. Other companies that received zero complaints in FY20 compared to a few in the year before included Larsen & Toubro, JSW Steel and Hindalco.

There were also companies which, in their annual reports, said that they have received zero cases of workplace sexual harassment between FY16 and FY20, possibly indicating the need for greater sensitisation, and need to build better support systems to encourage and empower people to register complaints. These companies include Bajaj Finserv, Coal India, Adani Ports and Special Economic Zones, Reliance Industries, UPL and Shree Cements.

Kedia observes that organisations in the formal sector have come a long way since 2013, but the level at which awareness is percolating down the corporate chain has been slow. “Close to 50-60 percent of the smaller companies do not have Internal Committees in consonance with the law. While most large companies invest time and money into PoSH compliance, many others still think sexual harassment is not their problem just because they haven’t received a complaint yet.”

This problem becomes more pronounced in Tier-II cities and beyond, and in the informal sector. Prasad of POSH at Work explains that there is no structured form of redressal for blue-collar and daily wage workers. “Women won’t even complain because who do they complain to? To the contractor? Or directly to the employer for whom they are working that day? If their family gets to know, they will stop the woman from going to work,” she says. “There is lack of awareness and empowerment, and we really need to work on addressing it.”

![posh-infographics-3 posh-infographics-3]()

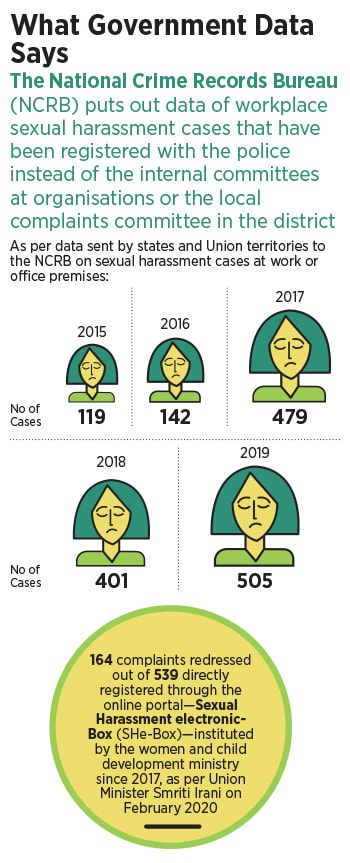

Any organisation—private, non-profit or government—with more than 10 employees [including part-time workers, interns and consultants] is covered under the PoSH law and has to constitute the Internal Complaints Committee [ICC]. For companies that do not have the ICC or if the complaint is against the employer himself, there is a provision of a local complaints committee (LCC) at the district level. The third option is to register a complaint either with the police or with the digital portal called Sexual Harassment electronic-Box (SHe-Box) instituted by the women and child development (WCD) ministry in 2017.

Reports, however, indicate that most LCCs are dysfunctional. According to a 2017 report by the non-profit Martha Farrell Foundation, which filed Right to Information (RTI) requests on LCCs, only 29 percent of the 655 districts in India had constituted local committees. Around 15 percent said they had not set up the committee yet and 56 percent districts did not respond.

There are many other loopholes too. As per the law, these committees must be headed by a woman, and must have at least four members, including one independent external member. “We have seen situations where the external member is the spouse or relative of the person running the company. In some cases, the presiding officer has been a man when the law clearly says it must be a woman,” says Prasad.

Roy of Serein believes that while the PoSH legislation effectively deals with complaints raised within the workplace, it should show more teeth when it comes to cases involving external stakeholders, clients, community members or travel outside the office. “In smaller towns, particularly, local committees can be empowered and reporting mechanisms can be made more stringent,” she says.

Data: Scattered and Fragmented

Companies under the ambit of PoSH have to file annual reports with their respective district government offices. Failure to comply attracts a penalty. The complaints that were registered with the police are recorded in the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) and the SHe-Box complaints are forwarded to the companies, which are supposed to launch an enquiry and get back to the WCD ministry [see box ‘What Government Data Says’]. In February 2020, Smriti Irani, union minister of women and child development said that the SHe-Box had received 539 complaints since 2017, out of which 164 had been redressed. There was no year-wise breakup provided for the data.

Lawyer Prasad says that Telangana and Noida district have digitised data collection and are strict about compliance. “For others, there are just bundles and bundles of papers being deposited in district offices and nothing has been happening about it,” she says. “Districts are now trying to collate data more proactively. As far as SHe-Box complaints are concerned, the organisation is supposed to report to the WCD ministry about action taken on the case, so there’s some sense of accountability. But again, there are no records to show what exactly is happening with your complaint once you’ve filed it.”

Aziz of Diageo India says that companies have come a long way in improving PoSH compliance since 2013. “The challenge is that there’s still a lot that needs to be done in smaller towns and villages. It goes beyond awareness. Company leaders have to walk the talk to make it [progressive cultural shifts] real for employees. They have to make conversations around workplace sexual harassment relevant in small towns,” he says. “We owe it to our country and our employees to bring everyone to the same level of consciousness and awareness.”

Tanul Mishra, CEO of fintech incubator Aftonia Lab, agrees. “We have gained a lot of ground in terms of legislation, but implementation involves creating companies where women can speak without fear of being judged, with more gender sensitisation workshops, and healthier workforce balance and inclusion,” she says. In the past two decades of her career across telecom, payments and startups, Mishra has encountered her share of sexism, including being asked if the company she founded is just a “hobby project”. She believes that while social biases will take a really long time to change, “right now the onus is on employers to foster a healthy environment without mistreatment.”

Image: Shutterstock

Image: Shutterstock