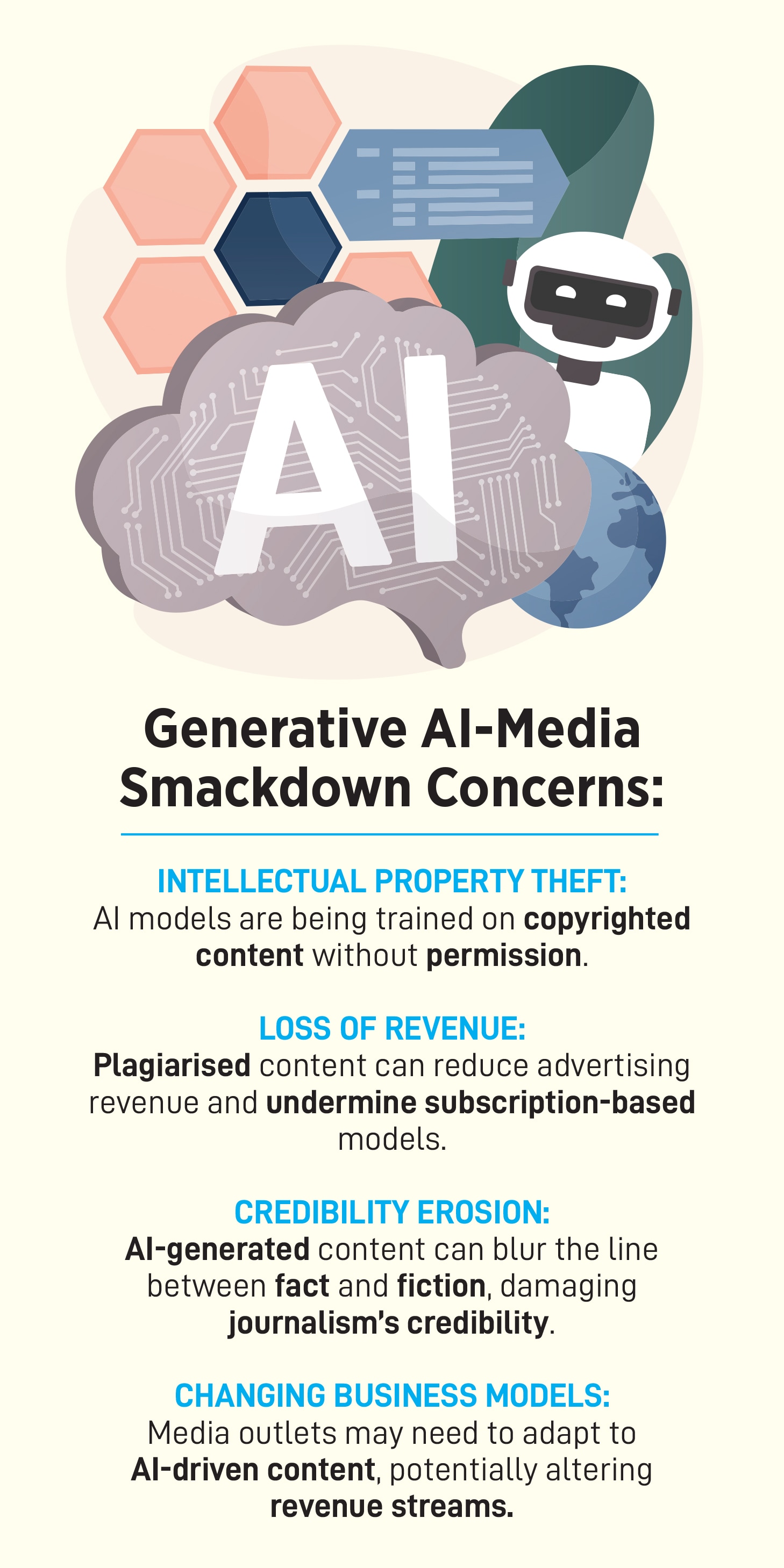

Generative AI startups like OpenAI, Perplexity AI, and big tech companies like Microsoft and Meta have created AI models that can generate content in milliseconds. However, the output is not entirely original, relying on pattern-matching through large amounts of data used for initial training. This data, which has been sourced from various articles, websites, books, essays, blogs and poems, is obtained at zero cost by the AI content makers. They also scan copyright-protected data without permission.

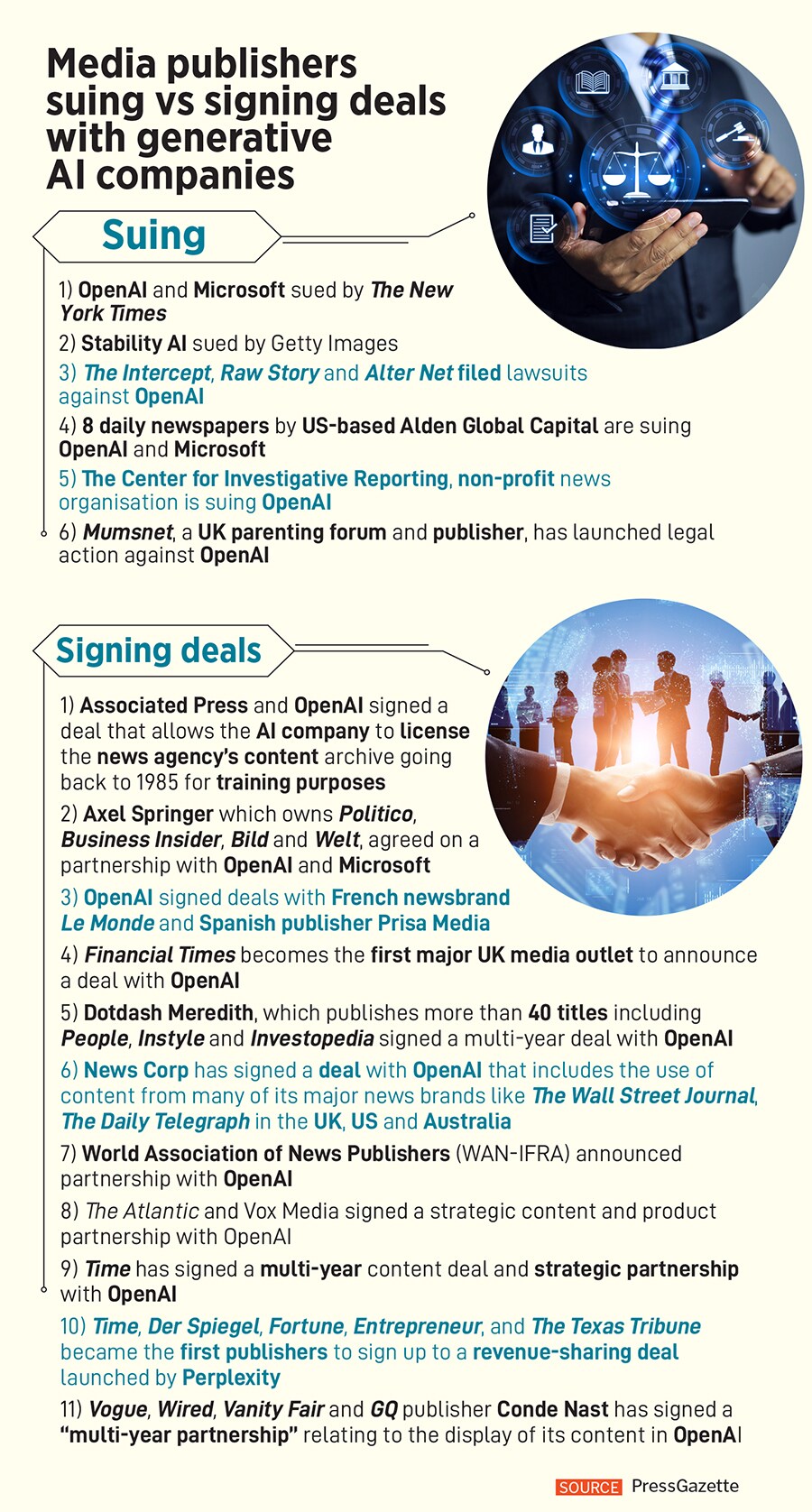

This has prompted news publishers to take action against AI companies. Newspapers, writers and novelists have alleged that AI “ingests" their work without permission. Complainants include author George RR Martin and newspaper The New York Times (NYT), which sued OpenAI and Microsoft for copyright infringement last December.

In May, eight newspapers owned by Alden Global Capital filed a similar lawsuit, claiming copyright infringement against OpenAI and Microsoft in the same New York court district where NYT lodged its complaint.

ChatGPT-maker OpenAI introduced a feature last year that allows publishers to opt out of having their content indexed by the company’s AI engine. Two years after its launch, users are becoming aware that many generative AI products are built on lifted information. The AI-powered search bar makes life easy for users, as they don’t need to open and read multiple links. Users just need to type the query, and the chatbot replies with a comprehensive answer after it scrapes the web for relevant information.

In July, Perplexity AI announced a revenue-sharing model for publishers a month after plagiarism accusations from Forbes and Wired. Under the new partner programme, every time a user asks a question and Perplexity generates advertising revenue from citing one of the publisher’s articles in its answer, Perplexity will share a flat percentage of that revenue with the publisher. That percentage counts on a per-article basis. This means, if three articles from one publisher were used in one answer, the partner will receive triple the revenue share, Perplexity’s chief business officer Dmitry Shevelenko explained in an interview with CNBC. Fortune, Time, Entrepreneur, The Texas Tribune and Der Spiegel were among the first news outlets to join the company’s ‘Publishers Program’.

While some publishers have gone to court, other news organisations have adopted a different strategy by choosing to strike licensing deals with the likes of OpenAI. They have agreed to provide them with access to their content for training and other purposes in exchange for monetary benefits. Last July, the Associated Press (AP) became one of the first outlets to sign an agreement with OpenAI. In exchange for giving access to its archive of news stories, AP would gain the ability to leverage OpenAI’s technology and product expertise.

The publishers feel cornered where, on one hand, if they deny these companies access to their data, their content may not be found. And if they do give access, they’re allowing these models to be trained with their content, and service providers like Microsoft and Google will keep generating answers for users—they don’t have to go to the original content providers. That also ultimately kills the business, explains Chirag Shah, professor at the University of Washington. “Reaching an agreement is a short-term solution. In the long run, it’s going to be really problematic, where there will be less traffic coming to the publishers. They will have to look for other business models beyond subscribers and the ad revenue."

Just before NYT filed its lawsuit in December, OpenAI announced another licensing deal with German media giant Axel Springer. In return for the right to train its AI engine on Axel Springer content, OpenAI agreed to give users of ChatGPT summaries of news stories from Axel Springer’s various brands, along with attribution and links to the original source. So far, OpenAI has announced 30 significant deals with tech and media brands. They describe the licensing deal as being part of a commitment to help publishers and creators develop new revenue models.

For publishers like the NYT, archived stories from many years may attract a bigger payout than OpenAI was willing to provide when the two were still negotiating. For other news companies, doubts still linger about whether the right way is to make a deal or go to court.

Surprisingly, the number of media houses rolling out the red carpet to these AI companies is higher than publishers restraining to support them. According to experts, if a newspaper decides to sue or license their content, it depends on their business model. For instance, striking a deal made sense for AP because it makes money by licensing content. Other publishers are more dependent on revenue generated by search traffic and might be reluctant to help an AI company produce content that gives readers no reason to click on a link.

![]()

It’s a new revenue source for traditional media companies, so reaching an agreement makes more sense, says Winston Ma, adjunct professor at NYU School of Law. Multimodal AI that can process and integrate multiple types of data, like images, text, audio and video, to make decisions and generate content could be revolutionary. “AI will not replace journalists because they can still come up with unique insights and reports. But journalists that are equipped with AI skills will replace journalists who are not."

The real challenge is that news media across the world is struggling to acquire and retain an audience because a lot of traffic is based on two sources: Search and social media. The existential threat is that both these are getting flooded with AI-generated content. Media publishers are faced with infinite competition because the cost of distribution is zero they rely on SEO content, where it’s an arms race for Google to keep search results relevant, and they’re struggling with it even now, explains Nikhil Pahwa, founder of digital media portal MediaNama.

AI is impacting discovery on the internet, and for many news publishers, anything from 50 to 80 percent of their traffic comes from a mix of search and social media only about 20 percent of the traffic is direct. “A large amount of usage will eventually shift to retrieval augmented generation (RAG)-based AI products like Perplexity. If discovery gets impacted, the reader acquisition funnel shrinks, and you get less traffic. The survival of news publications is going to become difficult in the next four years," adds Pahwa. That’s when the impact of AI will start showing on the top line and bottom line of companies. While MediaNama is trying to add AI features on the website, like proving short summaries of the article, they had to do away with paywalls in order to get access to a wider funnel of readers.

The media industry has gone through multiple transitions in the past, and it’s probably time for another one. “Regulation is necessary, but it should not come at the cost of innovation," says tech lawyer Raunak Rane. “At the same time, India needs to look at countries that have always been at the forefront of drafting policies around this." Government intervention will play an important role.

In India, there are copyright laws and policies to protect the work of human authorship. But there’s no framework that deals with artwork or any kind of work created using AI-based software, explains tech and media lawyer Leons Thomas Joseph. “One advice that I gave to AI startups building in this space is to create their original data to train their model. So tomorrow, when these apps are used, the data that is produced does not infringe someone else’s data."

![]()

There have been no legal battles in India so far, even when it leads in the adoption of generative AI in Asia-Pacific. According to a Deloitte survey, 93 percent of students and 83 percent of employees are actively engaging with the technology. Indian publishers have raised the issue with the Digital News Publishers Association and IT minister Ashwini Vaishnaw, who told them this will be covered in an AI regulation.

“My understanding from conversations with some publishers is that they would like to meet their short-term survival goals by partnering with AI companies rather than suing them. But they are not averse to the idea of suing them to ensure that there are partnerships," adds Pahwa.

An AI-enabled search engine is not going to replace a traditional search engine anytime soon. Because it has issues of reliability, costs and working with content providers. They don’t have a good model for that yet. The publishers are going to resist and not allow such companies to take their content and not get any kind of compensation, attribution or traffic. Gen AI companies are not there yet, says Shah.

The NYT alleges that the defendants’ generative AI tools rely on large-language models (LLMs) built by copying and using millions of copyrighted NYT articles, investigations, opinion pieces, reviews, guides and more. The petition claims that while the defendants engaged in wide-scale copying from many sources, they gave NYT content particular emphasis when building their models, revealing a preference that recognises the value of those works. Reportedly, NYT first tried to negotiate a licensing deal with the company prior to taking legal action.

The NYT alleges that the defendants’ generative AI tools rely on large-language models (LLMs) built by copying and using millions of copyrighted NYT articles, investigations, opinion pieces, reviews, guides and more. The petition claims that while the defendants engaged in wide-scale copying from many sources, they gave NYT content particular emphasis when building their models, revealing a preference that recognises the value of those works. Reportedly, NYT first tried to negotiate a licensing deal with the company prior to taking legal action.