Unsung Heroes: The silent women workers of self-help groups

Women like Gayatri Devi and Bhageerathy, along with their self-help groups, helped combat Covid-19 on various fronts across the country

Gayatri Devi (with the laptop), a resident of Jaipur village in Jharkhand’s Khunti district, is also a banking correspondent representative. During the lockdown, she helped open 350 bank accounts for poor people and migrant workers so they could receive money through the PM Garib Kalyan Yojana

Gayatri Devi (with the laptop), a resident of Jaipur village in Jharkhand’s Khunti district, is also a banking correspondent representative. During the lockdown, she helped open 350 bank accounts for poor people and migrant workers so they could receive money through the PM Garib Kalyan Yojana

Image: Ranjeet Kumar for Forbes India[br]Gayatri Devi’s day starts at 7 am. She has less than an hour to wrap up household chores before people start turning up at her doorstep seeking guidance with banking transactions. Apart from helping those who come home, Gayatri, a resident of Jaipur village in Jharkhand, goes door-to-door, armed with her laptop, in eight nearby settlements in the Naxal-affected Khunti district to help people open bank accounts, teach them how to transact, apply for loans or insurance, understand entries in their passbooks, and sometimes even recharge their phones.

“I have helped over 1,000 people across eight villages to open bank accounts, around 350 of which were opened for women in the thick of the lockdown. These accounts helped people receive ₹500 per month through the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan scheme,” says Gayatri. “There were times during the lockdown when daily transactions amounted to between ₹60,000 and ₹1,00,000.”

Gayatri, who is the pustak-sanchalak (chief bookkeeper) of two self-help groups (SHGs) in her village—including her own group Saraswati that has 11 members—believes in making women financially literate and helping them save as much as they can every week, even if it is ₹20.

That’s why she signed up to be a banking correspondent sakhi with the state government in Jharkhand: To teach villagers how to manage their money, and make them aware of their entitlements through government schemes. It was after demonetisation in 2016 that the 45-year-old first realised how crippling it can get for people who do not know what is happening to their money or how to safeguard their savings.

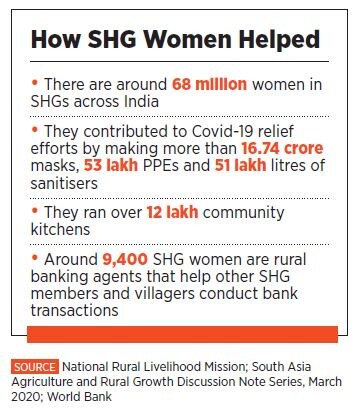

A similar fear had crept up in the wake of the pandemic this March. “Some people were afraid that the government would take the subsidy amount back if it is kept in their accounts for long, and hence would crowd outside my house or the banks to withdraw money without following physical distancing. But they had faith in me, so I ensured I addressed their monetary concerns during the lockdown, taught them how to practise safety precautions, and guided them through the difficult time,” says Gayatri, who also volunteered to go door-to-door to survey migrant workers who had returned to Jharkhand from various cities. Between May and July, she followed-up with close to 55 workers and their families about their employment status, helped them with food, sanitisers, masks, soaps and other essentials.Women like Gayatri working in SHGs across Jharkhand collected data of around 7 lakh returnee workers, getting details of their health, skill levels and job status so that the state government could frame policies for them. They did all this for no monetary benefit in return. Across India, around 68 million women working in SHGs helped meet the government’s urgent need for masks, PPEs and sanitisers, and also ran community kitchens to feed the hungry.

“Sab ghar pe aaram kar rahe the, aur hum samaaj seva kar rahe the [everyone was relaxing at home while I was doing social service],” adds Gayatri, who says the fear of contracting the coronavirus is what kept her motivated to step out to work and ensure others are safe at home. “Humko seva bhaav se khushi milta hai [serving others makes me happy],” she smiles. Gayatri has earned her masters degree in sociology through distance education.

It is a similar sense of service that prompted Bhageerathy from Palakkad district in Kerala to ensure uninterrupted availability of food supplement Nutrimix in anganwadis for children between six months and three years of age. “So what if schools and anganwadis have shut down? Food meant for children, especially those from vulnerable homes, should reach them no matter what,” she says.

Bhageerathy, 55, has been part of the Kudumbashree SHG framework in Kerala for the past 12 years and it was during this time that she earned her MBA in human resources. Today, she heads all the 19 units in Palakkad that produce Nutrimix, leading a team of 149 women. They manufacture about 135 metric tonnes of Nutrimix every month. “Before the 10th of every month, we distribute the food packets to the nearby anganwadis, from where parents would pick it up.”

In all, Kerala has 242 Kudumbashree units, owned and operated by more than 2,000 women, who supply Nutrimix to 33,000 anganwadis across Kerala. The women operating units in Palakkad, like others, get paid by the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) through the local panchayats, but their payments have been delayed for the past two months. That won’t stop their work, Bhageerathy says, as the women also turn to banks for financial support to keep the production running. “We work to ensure no child goes hungry. So we will keep up with manufacturing adequate quantities of food supplies for their sake.”

First Published: Jan 04, 2021, 17:33

Subscribe Now