A Gandhi, A Gypsy And A Rushdie: Garcàa Mà¡rquez's India Connect

The link between the Colombian writer and India is little known but multifaceted and fascinating just the same

Gabriel García Márquez, the genius of the imagination who died in April 2014 at the age of 87, may not have written on India, but he had a multifaceted connection with the country that can be boiled down to three people: A Gandhi, a gypsy, and a Rushdie. Gandhi first, and for that we must wind back to a magical morning in October, 1982, when the news broke that the Latin American writer who had enchanted the world with One Hundred Years of Solitude had been awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

In that joyous moment, Gabo became to Colombia what Pele is to Brazil. For this beautiful Caribbean country battered by poverty, drug violence and civil war, the fact that one of its countrymen had won the Nobel was akin to it winning the World Cup. And because Gabo had grown up dirt poor and could be as coarse as a sailor and as chivalrous as Don Quixote, celebrations erupted not just in Bogota’s linen-clad salons but in the country’s barrios and villages as well. Taxi drivers in Barranquilla, where Gabo had spent his early years as a journalist, heard the news on their radios and began to toot their horns in unison. One excited reporter asked a prostitute if she had heard, and she replied, yes, a client had told her in bed. This nugget would have delighted the new laureate, for not only are prostitutes—especially the trembling child prostitute—portrayed with extraordinary sympathy in his stories (his depiction reminds one of Manto’s Bombay prostitutes), he himself had lived above a brothel in his youth when he was unable to afford more respectable quarters. Publicly Gabo maintained that winning the Nobel would be “an absolute catastrophe”, but secretly he longed for it. And so, when the Swedish minister called his home in Mexico City with the news, he put down the phone, turned to his beloved wife Mercedes, and said: “I’m f@#$&”.

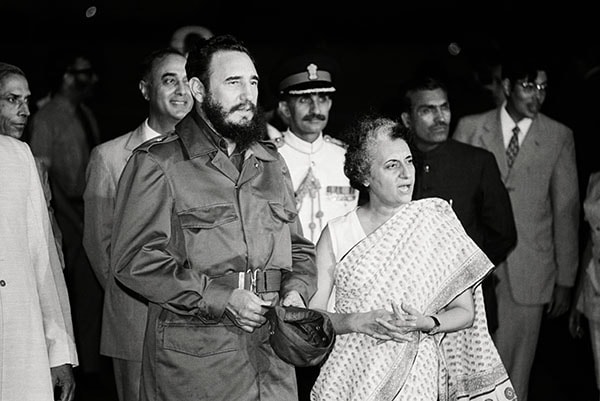

That day, his telephone was so jammed with calls that his old friend Fidel Castro was forced to send a telegram: “Justice has been done at last… Impossible to get through by phone.” Far away in New Delhi, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi thrilled to the news, not least because she happened to be in the middle of One Hundred Years of Solitude. In a lucky turn of events, Gandhi got a chance to meet Castro the very next month in Moscow, where they’d both gone to attend Soviet Premier Leonid Brezhnev’s funeral. Why don’t you bring your friend to India for the Non Aligned Movement summit next year, she suggested. Why not, said Castro. Image: Bettmann / Corbis

Image: Bettmann / Corbis

Cuban President Fidel Castro is met by Indira Gandhi on his arrival in India for the Non Aligned Movement summit

And that is how García Márquez accompanied Castro to India in 1983. When their plane landed at Palam airport, he remained seated, unwilling to disturb the protocol until Castro had disembarked and been welcomed. But Gandhi came marching up the aircraft steps demanding, “Where is García Márquez?” “From that time on, we were inseparable,” he told a Colombian diplomat. “She spoke French, and by the third day I felt as if Indira had been born in Aracataca.”

On that trip, Gabo spent an afternoon browsing at the late KD Singh’s The Book Shop in Khan Market. Although he and his family had been to India in 1979, this visit was a historic one, associated as it was with the seventh NAM summit, whose defining image, as many readers will fondly remember, is of the giant Castro engulfing a blushing Gandhi in a bear hug—she barely came up to his beard.

“Madam Gandhi—what a combination of delicate femininity and sheer power,” is what García Márquez, who had a weakness for powerful people, is supposed to have said, according to veteran Congressman Natwar Singh, who was present and had read Solitude after Sonia Gandhi recommended it to him. Indira Gandhi told her new friend that he must come back. “She invited me to go on a tour of India, organised by her, and I accepted. She said she would be in touch,” García Márquez said, his face clouding over. “Then I heard that she had been assassinated, and that was why I promised I’d never go to India again.”

Solitude was no doubt much discussed in the Gandhi home, which explains why Priyanka Gandhi recently chose to quote a “South American writer” who had just died, only to end up attributing a fabricated quote from the internet to the master. Priyanka might have known that “We must say what is in our heart” is vintage Hallmarkian, not Garciamárquian. How well he knew that some secrets of the heart bloom only in shadow and we are richer for them. As he told his biographer Gerald Martin, “Everyone has three lives. A public life, a private life, and a secret life.”

Multiple lives bring us to Gabo’s second and most idiosyncratic India connection: The Sanskrit-speaking Melquíades, whose ghostly reincarnations guide the plot of Solitude. This vegetarian gypsy with Asiatic features is one of García Márquez’s most enduring creations. If any character embodies the alloy of magical realism in its fullest aspect, it is this gloomy shaman who never lies and retails technology, wisdom, and prophecy—think of him as Steve Jobs, the Dalai Lama and Nostradamus magicked into one. Melquíades shows up periodically in Macondo with techno-bait like magnets, telescopes, and a magnifying glass as large as a drum. Macondo, of course, is García Márquez’s Malgudi, a fictional jungle village founded by the eccentric patriarch of the Buendias. Before he dies, Melquíades prophesises the future of the Buendia clan for the next one hundred years. These years will be scarred by love and madness, epidemics of rain and amnesia, war, and most deadly of all, incest, the sin that produces a baby with a pig’s tail. The birth of the deformed child marks the end of Macondo. In a horrifying climax, the newborn is stung to death by red ants even as the village is whipped into oblivion by a cyclone. All these events are accurately foretold by Melquíades, and since his prophecy is the sum and substance of the novel, Melquíades is none other than García Márquez himself. The Oriental gypsy is therefore the sutradhar of Solitude.

But—and this is the fascinating bit—Melquíades’ prophecy is a coded one, written on parchment in a strange script whose letters are described as “clothes hung out to dry on a line”. Only many generations later does one of the Buendias figure it out, and Melquíades’ ghost pop up to confirm that the language that looks like laundry is indeed his mother tongue, Sanskrit. Go to the local bookstore and buy the sole Sanskrit primer there before moths eat it up, he commands. Of all the incredible things that occur in this novel where men tattoo their penises and have sex with donkeys, the craziest is that Macondo should have a Sanskrit primer. It’s unclear why Gabo thought fit to throw a Devanagari curve ball into the plot—it’s not as if a single Sanskrit word is actually quoted in the novel—but it does serve as a linguistic bridge between the insular new cocoon of Macondo and the ancient world outside.  Image: Getty Images

Image: Getty Images

Salman Rushdie and film director Deepa Mehta at a screening of Midnight’s Children

And, finally, to the most significant connection of all: Salman Rushdie. The great modernist Virginia Woolf, whom García Márquez admiringly referred to as “a tough old broad”, rightly said that without Chaucer there’d be no Shakespeare, and without Shakespeare no Jane Austen. Similarly, it’s safe to say that without Solitude there would be no Midnight’s Children. Rushdie’s Indian masterpiece is indelibly shaped by the Latin American masterpiece of magical realism. Innumerable parallels exist between the two novels, the most recognisable being the similarity of their apocalyptic endings: Just as Macondo crumbles to dust, Saleem Sinai’s body crumbles into 600 million pieces, the population of India at the time, the year of Indira Gandhi’s Emergency. Rushdie obviously had other literary influences, among them Kafka, Borges, and the Arabian Nights (all three, incidentally, also influenced García Márquez), but Solitude touched something vital in him as a writer and an Indian. Here was a world as hot, crowded, superstitious and melodramatic as India, and here was a distinctive narrative style that allowed one to capture it in its entire splendour.

“When I first read García Márquez I had never been to any Central or South American country,” Rushdie wrote in The Telegraph. “Yet in his pages I found a reality I knew well from my own experience in India and Pakistan. In both places there was and is a conflict between the city and the village, and there are similarly profound gulfs between rich and poor, powerful and powerless, the great and the small. Both are places with a strong colonial history, and in both places religion is of great importance, and God is alive, and so, unfortunately, are the godly. I knew García Márquez’s colonels and generals, or at least their Indian and Pakistani counterparts his bishops were my mullahs his market streets were my bazaars. His world was mine, translated into Spanish. It’s little wonder I fell in love with it.”

Both García Márquez and Rushdie grew up in coastal cities and upset their fathers by wanting to be writers, both wrote about their home countries from abroad—Gabo from Mexico and Rushdie from England—and both are widely regarded as among the foremost novelists of the last century. But what separates them is love. Rushdie may be the superior writer in terms of cerebral power and big ideas, but he has never been able to write convincingly about love the way García Márquez has. In Gabo’s stories love can be ugly, fascistic and paedophiliac, but it is always overpoweringly real, it stinks of life. Love in the Time of Cholera, for instance, must rank as one of the most ridiculous love stories in literature. After 50 long years, Florentino and Fermina finally make love. Their bodies have the sour smell of old age and their bones are mouldering her breasts sag, he wears dentures—which she lovingly cleans—and initially he’s so terrified he can’t perform. Roll your eyes all you want, you’re also likely to find your eyes suspiciously moist at the erotic antics of these geriatrics and the way their love triumphs over the decay of time.  Image: Daniel Munoz / Reuters

Image: Daniel Munoz / Reuters

Garcia Marquez with his wife Mercedes upon their arrival in Aracataca in 2007

But Cholera is not easy to read, nor is Solitude. For those looking for a more accessible—but brilliant—introduction to Gabo’s writing, a good novel would be Chronicle of a Death Foretold, based on a true story. Two brothers are determined to kill their sister’s Arab lover, the handsome and arrogant Santiago Nasar. They announce this to everyone they meet. But despite the village having full foreknowledge, the murder takes place. The villagers appear to be in the grips of a lethal fatalism and inertia, and their inability to act makes them complicit in the murder.

Santiago dies the brothers stick their knives into his stomach, and his intestines tumble out into his hands. Into this gross moment, García Márquez introduces a touch of transcendental beauty: Santiago picks himself up and, carefully, flicks a fleck of dust from his entrails. Here is a man whose body will shortly end up as wormy dust, and yet he makes an absurd attempt to groom himself. Even in his death throes, his desire to keep going is relentless. In ‘The Waste Land’, TS Eliot intoned, “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” García Márquez, in the face of fear, flicks away a mote of dust, and with that delicate nod to Eros, flicks away death. His novels are beleaguered by cholera and poverty and honour killings—tragedies we are alas all too familiar with in India—but they also affirm that despite these afflictions, life, every last and blasted drop of it, is worth living. That is why we mourn him, why we return to his labyrinthine stories, and why we echo the words of Salman Rushdie and say, “Gabo lives.”

First Published: Aug 09, 2014, 07:06

Subscribe Now(This story appears in the Feb 05, 2010 issue of Forbes India. To visit our Archives, Click here.)