Indix: The 'Google of Products' Helps Retailers Take Real-Time Decisions

Sanjay Parthasarathy's Indix wants to be the last word in helping retailers manage business. And it is slowly getting there

When Sanjay Parthasarathy shifted base to India in 2009, after having spent nearly two decades in Microsoft, it dawned upon him that “everything had changed” about the country. He hunted for places to buy things for his kids and family, and realised by and by that search engines didn’t work well outside the US and the UK. “Google’s page rank system threw up results from the US and the UK only,” he says.

For some time, he toyed with the idea of starting a local search engine tuned to what was happening in India. After all, starting up was second nature to the man who “retired” (“quit sounds very wrong, I just decided to move on,” he says) as the corporate vice president of Microsoft’s Startup Business Accelerator (a division he created at the tech behemoth for building startups). “A lot of interesting work was going on at Microsoft, but a lot of it got lost in engineering. We wanted to see if there was a way to build new businesses out of these ideas,” he says.

But, as he found out later, in India, starting a local search engine wasn’t a great idea because the market wasn’t conducive. “The business model wasn’t there, and Google had all the oxygen. Ninety-five percent of search in India was Google,” says the 49-year-old Parthasarathy, an MIT alumnus.

He spent the next couple of years talking to people and travelling to conferences around the world “with no clear idea in the head”. “Now there is a great deal of energy and enthusiasm about startups. At that time, it was more about the economy,” he says. But he sat through conferences quietly and “just listened” to the CEOs and CTOs of the world. “That’s how the idea [of Indix] started… just by hearing 200 people,” he says.

When Parthasarathy incorporated Indix in December 2010, the idea was to start a search engine for numbers (prices). “Prices were interesting in a lot of different ways. People would pay to get knowledge of prices. Just like Bloomberg offers prices of financial instruments, our original concept was to create a Bloomberg for non-financial instruments,” he says. But, very soon, he realised that prices were just one attribute of products.

“Products have an incredible number of attributes: Colour, size, texture, manufacturer, seller, shipping codes, tags, reviews, etc. There is such a rich environment around a product and so much data that if we can get it, look at it, analyse it, and help people make decisions based on it, then that’s a business. That’s Indix,” says Parthasarathy, co-founder and CEO of the company, which is often dubbed the “Google of products”. “But what Google doesn’t do is organise it in such a way that you can analyse it, visualise it and take decisions based on it,” he says.

For instance, if an apparel retailer wants to take stock of a certain product, say, a black cashmere shawl, in its inventory, it can use Indix to find out a variety of things: The inventory size or the number of such shawls it stocks, stores with excess inventory, areas/cities where the product sells most/least, the product’s price in a competitor’s store, the kind of people buying it, the things people are saying about it, etc.

To provide the retailer such detailed information, Indix uses crawlers (a search engine that browses the web systematically for the purpose of indexing) and smart algorithmic filters to mine public websites for product information, which it then classifies into ‘catalogue data’ (static details like category, description, tags, etc) and ‘offers data’ (dynamic details like prices, promotions, availability, etc). The company then structures that data, analyses it in real time, and gets visualisation engines to throw up charts and insights for product managers—its chief target group. Depending on the results, the retailer can take real-time business decisions in terms of price changes, promotional offers, inventory management and more.

That is serious technology in one system. And to ensure its smooth functioning, Indix has minimised human interactions with the use of deep learning or machine learning—a concept where machines interpret data and provide analytics. “People are here to just code. You don’t need them for anything else. If you had them anywhere else, it doesn’t scale. Because humans can process data for hundreds and thousands of products. Machines can process for millions,” says Parthasarathy.

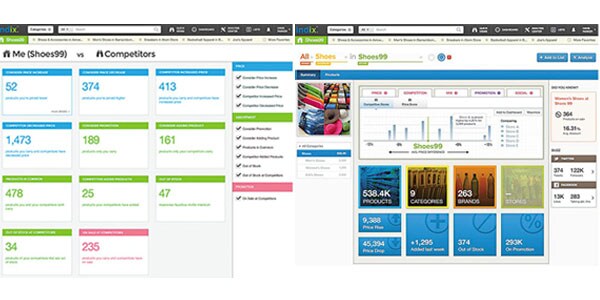

In its beta-testing phase, Indix carried out a demo of its product intelligence app with Shoes99—a fictitious online retailer

In its beta-testing phase, Indix carried out a demo of its product intelligence app with Shoes99—a fictitious online retailer

Achieving scale, though, hasn’t been difficult for the Seattle-based company (which also has a back-end office in Chennai). Since October 2013, when it launched in the market, Indix has built a database of more than 500 million products, and expects to cross a billion by next year. “The big issues are depth and speed. We are more than doubling data every few months. We also want to go deeper,” says Parthasarathy.

“Indix is second to Google in terms of scale,” says Sameer Brij Verma, principal, Nexus Venture Partners, which led Series A funding at the startup in March 2012. (Until then, it was entirely funded by Parthasarathy.) “They are a category-creating company in the product intelligence space and a glue between all stakeholders there. They have structured their database in a very intelligent way and in real time, and that was a clincher for us,” says Verma.

Despite growing its database at the speed of light, and lapping up 16 large customers in the US, including Microsoft, Drugstore.com (a health and pharmacy retailer) and OnlineShoes.com (a footwear retailer in Seattle), the company is yet to turn a profit. It has raised about $6 million from Nexus Venture Partners, Avalon Ventures and a clutch of angel investors in various rounds of funding over the last two years. “That is enough,” says Parthasarathy. “We are a team of 60 people now, 40 in India and the rest in the US. That is the biggest cost we incur,” he says.

Among the early investors in Indix is Parthasarathy’s friend and serial entrepreneur Vishal Gondal, who says, “A lot of companies are doing Big Data analytics, but Indix is doing next generation stuff.” He thinks the real revolution will happen when retailers begin to start and manage stores based entirely on the data available from Indix, and without the help of any market intelligence.

Besides being extraordinarily high-tech and holistic, the Indix app is beautifully designed and its visualisations are clean and uncluttered. “Sanjay thinks from a design perspective. He has focussed on even the font he would use for his product. This sense of aesthetics comes from his taste in art and the fact that he is an avid art collector,” says Gondal.

One of the challenges for the company is sourcing talent. “For companies in this space, the availability of skill sets is a problem,” says Bhavish Sood, research director at technology research firm Gartner. “Talent must understand data processing and information management and text-mining and data mining all at the same time. Advanced analytics is also a big challenge,” he says.

Parthasarathy has sourced his product team—which Nexus VP’s Verma calls “world-class”—from Chennai. He says, “People are more product-oriented here, unlike in the [Silicon] Valley. They come for the right reasons and not just for the pay,” he says. “Also, there is no chance of hiring fast in the US.” Indix’s sales and marketing team, though, is based in Seattle as they have to be “closer to the customers”.

Will Indix find an Indian customer in the near future?

“Not likely,” says the founder-CEO. “Because technology has never been about just technology. It is also about culture-readiness. And about competition to accelerate that readiness. The Indian market isn’t ready yet for this kind of a service.”

The company also plans to continue as a business-to-business player because building eyeballs, getting traffic and acquiring consumers is price-heavy and difficult. “You got to build a business and then invest in people and a culture. I have a much better chance of educating and partnering with business customers,” says Parthasarathy.

What, then, has Indix set out to achieve?

Says Parthasarathy, “This is the era of pervasive commerce. It is the model that powers the internet. And we are building an asset that helps commerce be different, more efficient and more interesting.” And all in real time.

First Published: Nov 21, 2014, 06:22

Subscribe Now