The future of jobs may be dark. It's time to get on the job: Mahesh Vyas

Pandemic-induced brain drain, skewed gender ratio and the inability to absorb low-skilled labour paint a dark picture for employment in India

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

Illustration: Sameer Pawar

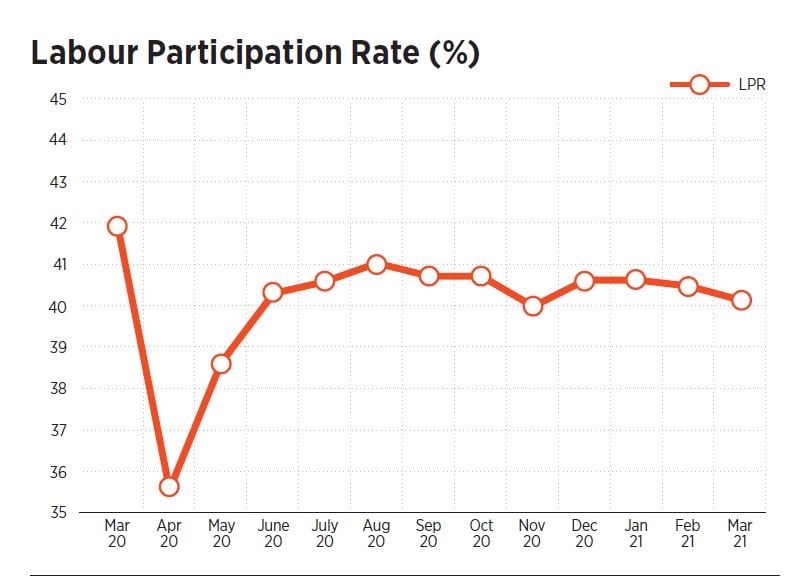

Before we address what India might start to see in terms of jobs and employment in the years ahead, at a time the second Covid wave rages on, we must understand how the labour market fared in 2020. The unemployment rate, according to the Centre For Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), was at a record high of 23.5 percent in April last year and then it slid to 10.9 percent in June before tapering off more in the months that followed. While the unemployment rate for a country always grabs headlines, what is far more critical is the labour participation rate (LPR).

Before we address what India might start to see in terms of jobs and employment in the years ahead, at a time the second Covid wave rages on, we must understand how the labour market fared in 2020. The unemployment rate, according to the Centre For Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE), was at a record high of 23.5 percent in April last year and then it slid to 10.9 percent in June before tapering off more in the months that followed. While the unemployment rate for a country always grabs headlines, what is far more critical is the labour participation rate (LPR).

The LPR is simply the measure of the proportion of a country’s working-age population of 15 years of age or more that engages actively in the labour market, either by working or looking for work. It tells us how many of the working-age population are willing to be employed. If this proportion keeps falling, it does not bode well for India’s growth story and for the well-being of its people.

The LPR for India has been falling systematically since 2016-17, when it was 46.1 percent. In 2017-18, the year that showed the full impact of demonetisation (announced in November 2016) and the July 2018 introduction of Goods & Services Tax (GST), the LPR fell by 256 basis points. It slid by 77 basis points in 2018-19 and then again by 14 basis points in 2019-20, to an average of between 42 percent and 43 percent before the pandemic.

Lasting impact of the pandemic

In 2020, the pandemic year, the LPR slid to 35.6 percent in April before climbing back marginally in June, but it has not yet touched the 41.9 percent level seen last March. So while the unemployment rate has recovered somewhat to 6.5 percent in March 2021—from high levels of 23.5 percent in April 2020—the LPR never repaired itself. A large portion of people who were part of the labour force are no longer part of it—it’s the lasting impact of the pandemic.

A country with a declining LPR over several years comes with its own set of concerns. It all depends on which part of the development cycle the country’s economy is in. Even in the West, like the United States of America, the LPR is falling, but that is because the per capita income of the country has risen enough to enable people to quit the labour market at a particular age. For a developing country such as India, a falling LPR means that the country is unable to provide jobs to a thriving labour force. Our working population is increasing, but it is not getting jobs, which is not a good sign.

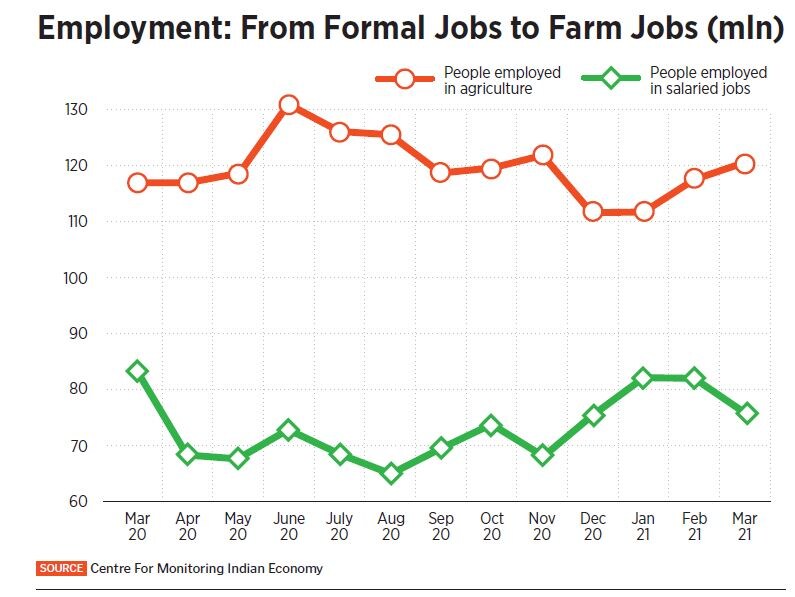

The problem of high unemployment is only a recent phenomenon. In India, till the 1990s, the unemployment rate was extremely low, of around 3 percent for several years, and people picked a low-wage job because they could not afford to remain unemployed. The opening up of the economy in the early 1990s led to the great shift from low-productivity farm jobs to higher-productivity factory jobs.

But this growth petered out in recent years. The biggest loss of employment in 2020-21 was among the salaried employees.

As of March 2021, there were 76.2 million salaried employees. This was 9.8 million less than the 85.9 million salaried jobs observed in 2019-20.

A falling labour participation rate means the country is unable to provide jobs. Also, jobs at the lower end are likely to vanish soon

A falling labour participation rate means the country is unable to provide jobs. Also, jobs at the lower end are likely to vanish soon

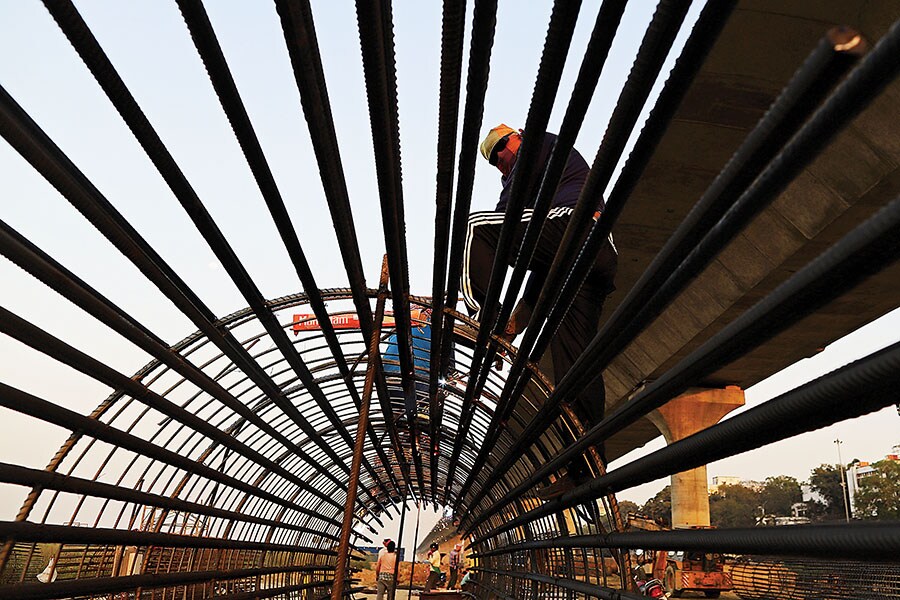

Image: Anindito Mukherjee / Bloomberg via Getty Images

Gender bias

Every time there is a shock to the economy, be it demonetisation, introduction of GST or the global slowdown, the people who suffer the most are women and the youth. When the going gets tough, data shows that women quit the labour market due to adverse conditions. In difficult economic conditions, enterprises prefer to retain men rather than women. People who quit the labour market are young women. When they enter the labour market in their mid-20s, they don’t get jobs. This is odd because in the last five years, the number of women graduating is much higher than men.

The LPR for men in 2019-20—pre-pandemic—was 71 percent and just 11 percent for women.

In the same period, the average unemployment rate for men was 6.3 percent and 17.5 percent for women. For March 2021, the LPR for men was 66.9 percent and just 9.7 percent for women while the unemployment rate for men was 5.7 percent and 12.7 percent for women. Data suggests this is an urban phenomenon because, in rural India, women might get farm-related jobs.

The biggest impact of this on the economy is that India completely loses on its demographic dividend—if 71 percent of men are working, then there is no headroom for more men to work.

All the headroom of people adding to the workforce and contribution to growth in household income is women. But women do not join the workforce.

Pandemic second wave: ‘W’ shaped recovery

The second wave will give a further jolt to the recovery of the labour market, with a concern over livelihood. In October 2020, the average household income was ₹20,000, which was 20 percent below a year earlier, according to CMIE. This income will have dropped further. Its impact in future will be troublesome because the average does not tell us what the distribution is by income groups. We know the savings rates and income for the richer people have risen, but they have fallen for the poor.

So there was a ‘K’ shaped recovery for the economy, but this is widening and looking like a ‘W’ shaped recovery. I am not sure how deep the ‘W’ is going to be, but it does look like the ‘K’ will widen for sure. Income inequality and poverty are getting worse.

We have seen the fragility of the salaried job market during the pandemic’s first wave (see chart). As the second wave deepens, in the short-term, more people will move into farm jobs as disguised employment and there will be a gradual decline in the absorption of labour in the organised sector. This is because the businesses of enterprises such as micro- and small businesses (MSME) are shattered and their capacity to absorb labour is declining rapidly.

The long-term impact is that companies will increasingly move towards artificial intelligence in the services sector in a bigger way, automation in the manufacturing sector and mechanisation in the mining sector. This will mean fewer jobs for output.

The jobs at the lower end will vanish soon. The government has also virtually frozen hiring. So where will the jobs come from?

Future: Contracts without social security

A lot of the employment is moving away from good quality jobs with social security to contractual jobs with no social security. Even jobs which are increasing are of poor quality. The government is still implicitly promoting jobs in capital-intensive industries.

The recent production-linked-incentive schemes announced by the government—in some cases to manufacture mobile phones—are capital-intensive and very low on labour absorption. But it is particularly important for India to have industries which absorb large amounts of low-skilled labour and there is no push towards this. In fact, we have a paucity of high-skilled labour.

Automobile manufacturers are increasingly focusing on hiring contractual labour at the other end we fear excess labour could get laid off when government or state-owned undertakings get privatised.

Expanding the startup ecosystem has made a huge difference to the labour ecosystem, having absorbed both skilled and unskilled labour. Look at Urban Clap, which hired skilled labour and deploys it well. Others like foodtech giants Zomato and Swiggy have employed lesser-skilled labour well.

In the mid-1990s and early 2000s, the rush was to seek a high-quality information technology (IT) job, but that is not true today of the jobs which startups offer. We also need a big push for hiring of skilled engineers in manufacturing and in IT… the level of engineers being hired is not the same as those hired between 1960s and 80s, and even the 1990s. India’s wage growth has also been declining during the pandemic. Formal workers’ wages in India have been cut by 3.6 percent while it was a 22.6 percent cut for the informal workers, according to a 2020 global wage report from the International Labour Organization (ILO).

undefinedA lot of the employment is moving away from good quality jobs with social security to contractual jobs with no social security[/bq]

It is difficult to assess what kind of jobs will emerge. We have a conundrum on the demand and supply of jobs. We have a large supply of low-skilled labour for which there is little demand (thousands say they do not find jobs) and a short supply of high-skilled labour—such as coders—for which there is high demand (corporates say they cannot find high quality labour). The situation does not look good, but we should be hopeful for a better tomorrow.

Brain drain

Also, it looks like the rest of the world is coming out of the pandemic much faster than India is. In the current fiscal, with living conditions being tough, the vaccination drive slow and fewer jobs available, the educated and high-skilled Indians might be tempted to leave the country to seek opportunities elsewhere.

A critical question also arises: With the current LPR of 41 percent, how many new jobs does India need to create? This figure works out to around 8 to 9 million each year (which is not happening at all). The number of people aged above 15 is growing at 20 lakh a month and with an LPR of 41 percent, it works out to 8 lakh per month. Multiply this by 12 and we get just over 9 million jobs if we are to accept our current LPR. [The global average LPR, according to ILO model, was about 59 percent in 2020].

We need to recognise the employment problem and at a public policy level. There is a disconnect between economic policymaking and the political compulsions—of making unrealistic promises to the electorate—arising out of the situation. It would be better if the political establishment, both the Centre and states, assigns direct attention to the problem of employment.

â— As told to Salil Panchal

â— The writer is managing director and CEO of CMIE

First Published: May 19, 2021, 14:26

Subscribe Now