From headless chicken to golden goose: How Nandu's came into its own

Naveen and Narendra Pasuparthy have made the six-decade-old Nanda Group a formidable player in the poultry business. The siblings are now betting big on their brand Nandu's

The poultry market looked like a headless chicken. “It was absolute mayhem," recalls Naveen K Pasuparthy, who came back from the US in 1995 and joined the family business of livestock farming started by his father PS Nanda Kumar in 1963. In February 2006, India reported its first case of avian influenza (bird flu) TV channels went berserk with their news coverage, a fear psychosis gripped the nation, and chicken prices crashed by a staggering 85 percent.

The second-generation entrepreneur got his first crucial learning: The livestock business has a zero shelf-life. “And when you don’t have shelf-life, you get slaughtered like chicken," says Naveen, who studied in the US, and worked there selling voice and data communications for a multinational company. “I never wanted to come back and join the family business," he confesses.

A ‘Taliban’ and ‘hostage’ situation, though, compelled him to fly to India, Naveen explains, saying his mother acted like a professional extortionist. “If you want your brother to study in the US," she outlined her unconditional demand, “you will have to come back home". To save the ‘educational life’ of his younger brother, Naveen sacrificed his ‘professional life’. “That’s how I got blackmailed," he says, adding that he was compelled to come back in 1995. The hostage negotiations in Afghanistan, he says jokingly, could well trace their origin to his house and the way his mother acted. A decade later, in 2006, he was wondering if joining the family business had been the right move. He could see his chicken empire crumbling. “I felt helpless. There was little that I could do," he recalls.

His father, though, stayed calm. “What comes down has to go up, son," he tried to comfort Naveen. “And what goes up has to come down," underlined the patriarch who also shared another pearl of wisdom: “When you make money, spend little. Save for the tough days." Naveen braced himself to survive the torrid storm and continued with the business of poultry breeding, hatcheries, animal feed manufacturing, contract farming and poultry disease diagnostic labs.

Two years later, in 2008, Naveen’s younger brother was feeling like a headless chicken. A software engineer, Narendra completed his master’s in information science from the US, had a stint of over eight years at two startups in Silicon Valley and came back to India in 2005 to restart and relaunch Nandu’s, a value-added frozen product business started by his father in 1989. Due to limited appeal and infrastructure hurdles—cold chains were still missing—the vertical was shut down in 1993.

Two years later, in 2008, Naveen’s younger brother was feeling like a headless chicken. A software engineer, Narendra completed his master’s in information science from the US, had a stint of over eight years at two startups in Silicon Valley and came back to India in 2005 to restart and relaunch Nandu’s, a value-added frozen product business started by his father in 1989. Due to limited appeal and infrastructure hurdles—cold chains were still missing—the vertical was shut down in 1993.

“Back then, who understood the concept of chicken nuggets, burger patties and kebabs?" says Narendra, who relaunched the brand in 2005 with a new look, logo, and products, such as a range of over two dozen Indian value-added products like chicken biryani, curries and curry paste. The products were developed using ‘retort technology’, which did not require refrigeration. He tried for two years, but the business still faced the problem of limited appeal. “The market was not yet ready, and we were again well ahead of the time," he says ruefully.

In 2007, Nandu’s was shut down again, and Narendra now tried his luck with the business of DVD rentals. The idea was simple: Indians loved watching movies, so they should also fall in love with a movie rental service. The assumption carried weight. Egged on by his vision, the hero imported machines from Italy, set up a vast infrastructure and expanded operations. A year later, entered the villain. “Piracy killed my business," he rues. Three years after coming to India, Narendra had two failed ventures on his CV. In 2008, he went back to the poultry business, and started looking after the UAE operations. Eight years later, in 2016, the quintessential entrepreneurial itch troubled him again. Narendra relaunched Nandu’s in the form of an omni-channel meat retail brand that offered antibiotic-free products.

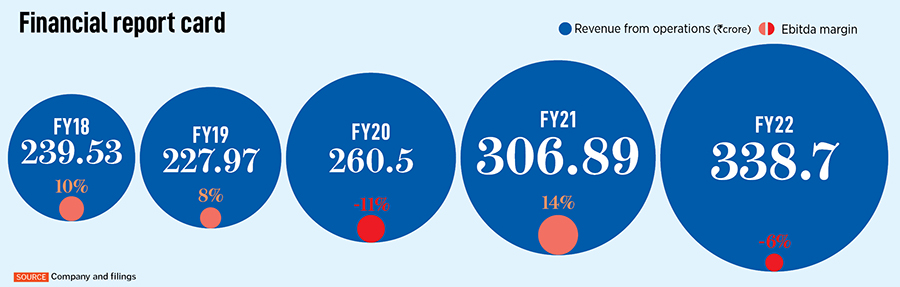

Fast forward to 2022. Narendra and Nandu’s were third time lucky. From a revenue of ₹9.27 crore in FY18, Nandu’s jumped to ₹67.52 crore in FY22 it has 55 outlets across Bengaluru and Hyderabad, and now plans to set up stores in Chennai and Pune. The Nanda Group, meanwhile, has also improved its fiscal report card during the same period: From ₹239.53 crore to ₹338.7 crore.

Industry analysts attribute the success of the group to a host of factors.

The Nanda Group, underlines food and beverage expert KS Narayanan, was one of the pioneers in making investments in the back-end farms, initiating contract farming, and maintaining and developing relationships with livestock farmers. “This helped Nandu’s in owning the entire supply chain," he says. What this also meant, he continues, is that the brothers were able to set up a transparent and traceable supply chain, which is critical in such kind of businesses.

Shankar Rao (second from left), then animal husbandry minister of Karnataka, with Nanda Group’s PS Nanda Kumar (third from left) at a farm in the 1960sImage: Courtesy Nanda Group

Shankar Rao (second from left), then animal husbandry minister of Karnataka, with Nanda Group’s PS Nanda Kumar (third from left) at a farm in the 1960sImage: Courtesy Nanda Group

Commenting on the group’s bullishness with the B2C arm, Nandu’s, Narayanan maintains that the brand has a huge edge in the meat market, which is highly unorganised and has a lot of health and hygiene concerns. By setting up retail outlets that present a hygienic front-end and by owning the entire back-end, the group has been banking big on its promise of selling antibiotic-free and safe meat products. “During and post-Covid, this helped the brand," he says, adding that the move to stay confined to Bengaluru and Hyderabad for the first few years helped it understand the market and consumers, and reduce cash burn, which any operationally heavy consumer venture would face in the initial phase.

Narendra, for his part, points out another factor behind the success. “Meat is an extremely passionate buy," he underlines. The entrepreneur tried to understand the psyche of a consumer, fix the broken meat retail experience and tried to make the buying process inclusive. Two women architects were assigned the task of designing the retail outlets. The brief was simple: Families must feel welcome when they enter the stores. “A mother should be able to bring her child to the store and feel very comfortable," he says.

The brand promise of antibiotic-free meat also helped it win the consumer’s trust. Though there were sceptics—a chicken is a chicken after all—the brothers stuck to their guns. “We are very passionate about sustainability and clean food," says Narendra. It took about eight months of trials and field formulations to scale production without antibiotics. Every process in the back-end was strengthened, feed formulations were changed, trials were conducted on around 4 lakh birds, and breeding stock and vaccination schedules were tweaked. It was not easy, he underlines, to convince every stakeholder to play a differentiated game. “But we won," he says with a smile.

Interestingly, there was another battle that the siblings won. It was the Nandu’s-versus-Nando’s fight in 2006. The South African Peri Peri chicken brand dragged the home-grown meat warriors to court over the brand name. Their argument was simple. Nando’s, they argued, was named after the founder Fernando Duarte. The brothers, in their defence, pointed out that Nandu’s was named after their father Nanda Kumar. After a year or so of intense legal tussle, the brothers prevailed. The father’s name won over the founder’s name, as Nanda Kumar had got the name registered much before the South African brand.

The brothers are now looking to scale operations. But there will be no haste, and sustainability will be the key. “We have been there for six decades, and we will keep growing," says Naveen.

First Published: Aug 12, 2022, 14:48

Subscribe Now