We do not talk enough about people who own two-wheelers. How do they live? What do they think? People in the government have to think of this large mass.

For example, when we speak about 100 percent electric cars… are these people who are scooter-owners going to have electric cars? Not in the next 20 years! So, what should they do?

They constitute the bulk of the people commuting in the country. We have 270 million two-wheelers today. They consume two-thirds of the petrol in the country. And 46 percent of road deaths are of two-wheeler riders. What should be done for this segment? We have not handled the problem of two-wheeler owners.

Putting six airbags in cars does not help them. That makes it more difficult for two-wheeler owners to buy cars by making them more expensive. When BSVI [emission norms] was introduced, two-wheeler sales collapsed because of the increased cost. People postponed their decisions to buy two-wheelers. It is only now that we have reached the same level of two-wheeler sales.

Entry-level car sales have similarly collapsed, having gone down by almost 50 percent because of the higher cost of compliance—both safety and environment.

Q. So, how do we help two-wheeler buyers become car buyers?

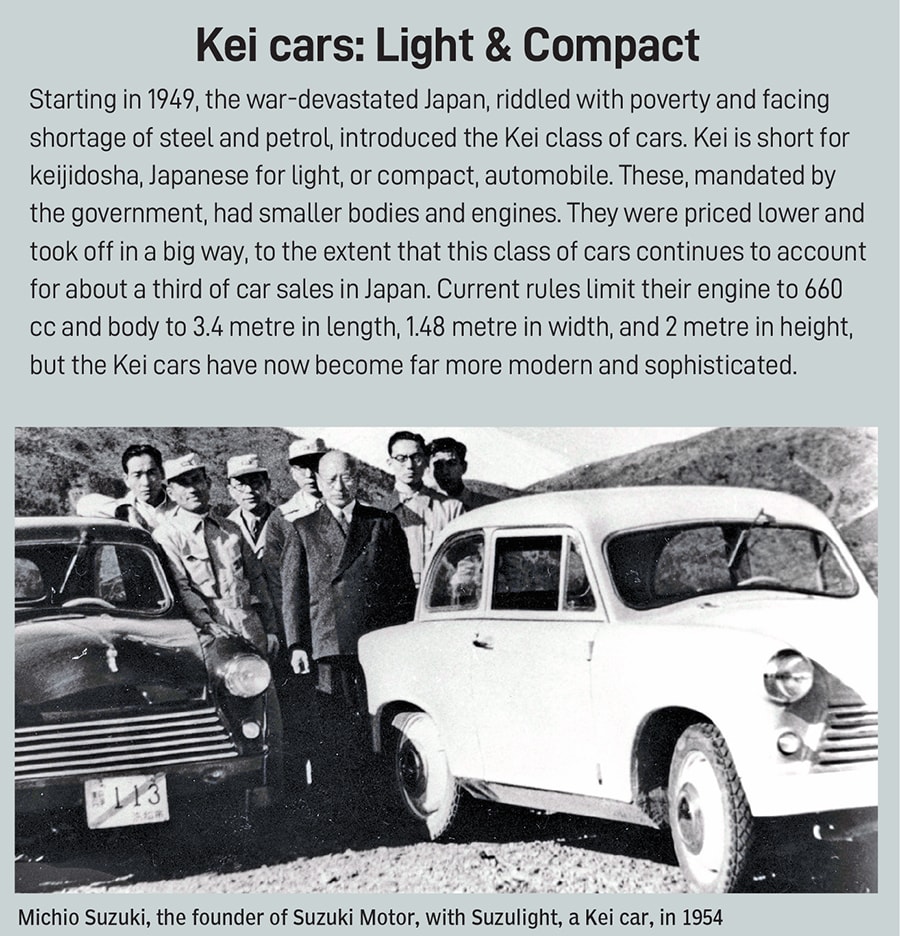

In the 1950s, Japan had almost a similar situation in relation to two-wheeler use. Large numbers of people in small towns were using two-wheelers. At that time, Japan considered cars to be a luxury or sin industry. Then it decided that they were not, and introduced the concept of the Kei car—small cars with limited space. They lowered the tax on that car. The safety requirements were not the same for them as for the bigger cars.

Scooters are no longer used for commuting in Japan now. More than a third of cars sales in Japan today are of Kei cars.

Q. How are Kei cars different? You mentioned taxation and safety compliance.

Compliance levels and tax levels are different. They are made for small towns. People do not use these cars to go on highways and long distances.

Q. So, they can be good city cars in India as well.

What does India need? Firstly—I do not have the statistics—but my sense is that the bulk of the driving people in India do is within the city. Intercity driving is limited. So, why do we design cars which are only for highway driving at high speeds? Is that the correct thing for India?

Q. What will make the Kei car in India a reality?

Why don’t we have, as a policy, something similar to the Kei car in India, which would essentially be a city car? Perhaps not for Delhi or Mumbai, but for all the thousands of B- and C-class cities where people can use these cars in place of two-wheelers. They would be essentially city cars. Lower specifications and lower taxes will make them affordable. That’s the route I think we should take.

![]()

Q. Are the Kei cars in Japan allowed to go on highways?

They are, but nobody goes. Of course, these Kei cars have also become sophisticated today, because everybody in Japan has a lot of money now. They can afford it.

Our problem in India is that the scooter-owner’s ability to upgrade his living is limited. How much does the per capita income increase every year? Not much, and that too on a low base. How quickly can he upgrade?

People say Indian aspirations have changed and everyone wants to upgrade to SUVs (sports utility vehicles). That is utter nonsense! Do they mean to say these people riding scooters want to buy SUVs and therefore are not buying small cars?

Why is everybody projecting 1 to 2 percent growth rate for cars this year? Because the segment that is growing is a very small part of the total universe of cars. If 80 percent of the market is not growing, how much growth can the 20 percent have?

Q. Rahul Bajaj used to say that the first family vehicle in India is a Bajaj scooter.

Yes, at that time that was the best thing.

Q. Even now, if you look outside the big cities, for many people, the first family vehicle is a scooter.

Because they have no choice. They cannot afford anything. We sell 3.8 million cars a year. Forty years ago, we were selling 40,000 cars a year. It all happened largely because the small car came in at that time: Maruti 800, which was priced very reasonably and led to rapid motorisation. That is not happening anymore.

![]()

Q. How will that kind of revolution happen again?

Same thing: The equivalent of a Kei car and well-thought-out policies on taxation and regulations. Some years ago, when all the higher standards were enforced, I had at that time made a statement that for India you have to rethink this because the scooter is the most unsafe vehicle. If the scooter owner upgrades to a car, the safety factor goes up manifold. But if you make the car out of his reach with all the new standards, you are making him continue with the scooter. So, are you increasing safety in India? But the media said, “Mr Bhargava does not want safe cars, Maruti does not want safe cars." It is not a question of wanting safe cars, but whether we can afford safe cars.

We often tend to aim for the best, forgetting that to get to the best you usually have to go through several stages of development. Many times, fair or good has to do instead of the best. But people do not understand that.

Q. But even in Kei cars, emission norms have to be the same, right?

Emission has to be controlled. The answer to that is ethanol. We are not able to develop our biogas potential. We are subsidising all kinds of other activities but not biogas. Biogas can be a totally clean fuel and available everywhere. Use biogas, use ethanol for small cars, then CNG (compressed natural gas).

Q. If we were to have a separate category of cars, like the Kei car, what are all the ways in which it will be different?

It is shorter in length. Today the small car is defined as under four metres. Our concept is that we can get a car of 3.6 metres, make the width less, limit the engine capacity. There is also a question whether one can limit the speed, but to that I don’t know the answer today.

![]()

Q. Perhaps a city car need not have a large boot.

No, it does not. That is why biogas and all become easier.

Q. Because the cylinder can fit in the boot. On electrification, have we figured the way ahead yet?

The problem in India is that electric cars are as clean as the electricity generation. At the moment, electric generation in India is not at all clean. Everybody says we are putting up a lot of [renewable] capacity, but that itself will not suffice unless you also provide a lot of storage.

Q. Because of the intermittency problem.

Many things interfere with the production of renewable energy, especially solar. How do you deal with the fluctuation without either thermal backup or storage. Storage means a huge amount of battery capacity is required.

The second question is, the infrastructure for distribution of power is exceedingly weak. Look at Noida [this interview took place at Bhargava’s home in Noida]. We have breakdowns all the time. If you look at charging of cars, even to have minimum capacity, it is 3 KW. That takes seven to eight hours to charge. Fast chargers are 18 to 20 KW but that cannot be at houses. Let’s take a colony like this. We have 800 houses here. If the bulk of the people here got an electric car each and need 3 KW for charging, what will happen to the grid?

Q. So, we should develop the charging infrastructure.

It (charging infrastructure) will happen, but it will take time for it to happen. I am not saying it won’t happen, but it takes a much longer time.

The other factor one must remember is that emission has to be reduced each year. You cannot say I will do only electric cars and not bother with the rest of the emission. Policy must also be directed towards saying how to minimise the annual emission from the transportation sector. Petrol and diesel cars are the biggest emitters of carbon compared to all other fuels. Today, taxation on all cars is the same, except electric cars. Whether I use hybrid or petrol or diesel, there is no difference recognised. So, people buy the cheaper diesel cars and maximise pollution.

Q. Some states like Uttar Pradesh have waived registration fee on hybrids.

Haan, thoda sa fark pada hai (yes, that has made some difference). The fact is, they have differentiated between a hybrid and a petrol car. But what about GST (goods and services tax)? It is high: 43 percent.

Q. Including cess.

Including cess, leaving out the state taxes, which vary from state to state.

Q. In the past we saw that Maruti for many years did not enter the diesel segment.

Again, government policy. The difference between petrol and diesel had become huge—at one point Rs 32 [a litre]. We were basically a petrol carmaker. Around 2010-11, our market share dropped from 50 percent to 38 to 39 percent because people were not buying petrol cars. So, we had to get into diesel. Again, the policy changed. The difference once again came down to Rs 10, and then the new emission norms came which made diesel more difficult to meet regulations, so we gave up diesel.

Q. But when Maruti did enter diesel, it became a dominant player there. Do you see a similar thing happening when Maruti gets into electric? Will it transform the market?

Too early to say. We have not even sold our first electric car.

Q. But usually when Maruti enters a segment, things happen. The same thing happened when you entered SUVs in a big way.

We entered late, but now we are the leaders. We have the advantage of volume production, of a far-far more extensive sales and service network, and of a great deal of customer confidence in the brand. When we make a product, the Japanese take a lot of care to put it in the market, the best they can do. Their level of best is better than most.

I think we should do well in electric cars. But I see a lot of limitations in large penetration of electric cars in the market in India at least in the next 10 years. It is largely a question of affordability and infrastructure.

I am not talking about public charging. If you are going to buy an electric car, almost certainly you will buy it only if you have a place at home to charge the car. I am not talking about taxi companies, but I cannot imagine many individuals buying an electric car and relying on public charging. No way! When will I need public charging?

![]()

Q. Highway driving…

When out of city. But the amount of out-of-city driving is limited.

Remember that public charging is much more costly. And most people who have invested in it are losing money because there is not enough utilisation. Expanding public charging facility is not necessarily the right decision in the Indian context. It is fine in the United States, because everyone there travels by road, even long distances, because flying is expensive and railways is hardly there.

Q. So, we need to change our approach?

You cannot improve unless you recognise that something is wrong. The best way of making progress is to learn from mistakes. That means you recognise a mistake and what caused the mistake, and instead of punishing the guy who made the mistake you use that experience to improve for the future. That is the Japanese philosophy and it is clearly the best philosophy. Who will want to innovate when I know that if something goes wrong my head is on the block? Then I will continue with things as they are. That is why governments have this huge importance for precedent? If you always follow precedent, will you ever improve?