No country for migrants

The lockdown has brought to light the plight of daily wage labourers and the nation's apathy towards them

Migrant labourers from Delhi scramble onto buses heading for their hometowns in Uttar Pradesh, following the outbreak

Migrant labourers from Delhi scramble onto buses heading for their hometowns in Uttar Pradesh, following the outbreak

Image: Madhu Kapparath

“When the work is over

We are but coolies and sailors.

And yet when the boat is slink

We alone come to pull it out of the mine.

We give everything

like the sacrificial cow

Only to find ourselves neglected now."

Song of the workers (Sramiker Gaan) by Kazi Nazrul Islam

Islam, arebel poet of his era, read this verse in 1924 at a peasants’ conference in Krishnanagar on the outskirts of Kolkata. His words ring true even today.

After the government announced a nationwide lockdown on March 24 to prevent the spread of coronavirus, lakhs of migrant labourers and daily wage workers were stranded. They couldn’t go back to their villages as there was no transport arranged for them. Visuals of hordes of them walking back to their homes, thousands of kilometres away, with children in their arms, brought their plight in the open.

Ram Roop Sahani is among those who’s stuck in Mumbai because of the lockdown. On a scorching Monday afternoon in April end, he and his co-workers are standing in a queue in suburban Mulund to collect food that was being distributed by local residents. Sahani hails from Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh (UP) and works at a construction site in the city. On a good day he earns about Rs 600 while on other days he makes roughly Rs 400 a day. “I don’t have any work because of the lockdown. I have borrowed Rs 5,000 from my seth [contractor]… I am waiting for work to start so that I can repay him and go back to my village,” says Sahani, adding that some of his co-workers left for their villages in heavy goods trucks before the lockdown was enforced.

Forbes India spoke to at least 10 labourers who are finding it difficult to survive in the absence of work, adequate food and money. Mohammad Ashfaq Khan, 19, from Shalimar in Srinagar who works at a local restaurant in Mulund (West) is in a dilemma whether to stay here or go home once normalcy returns.

The ones wanting to go back aren’t just labourers who survive on daily wages. Rajan, for instance, who has been running a snacks corner in Mumbai for over a decade, has been wanting to go back to his village near Chennai, Tamil Nadu, along with his wife, both in their sixties. “I’ll come back only when things are normal. I won’t return till everyone opens their shops," he says.

The government has asked employers to pay their staff regularly during the lockdown. Ashfaq is fortunate that his boss Jatinder Singh has been looking after him. Singh runs a QSR called Veerey Da Dhaba, which he bought four months ago, apart from manufacturing small cans for 32 years. Singh claims the lockdown has resulted in a monthly loss of nearly Rs 10-15 lakh. “The factory is in dire straits and the business is facing mounting losses. I have 8-10 labourers of which half have gone back home… it will be difficult to find labourers once things start to open up,” he says. Singh’s restaurant has eight workers and four of them, including those from Nepal and Kashmir, are with him during the lockdown.

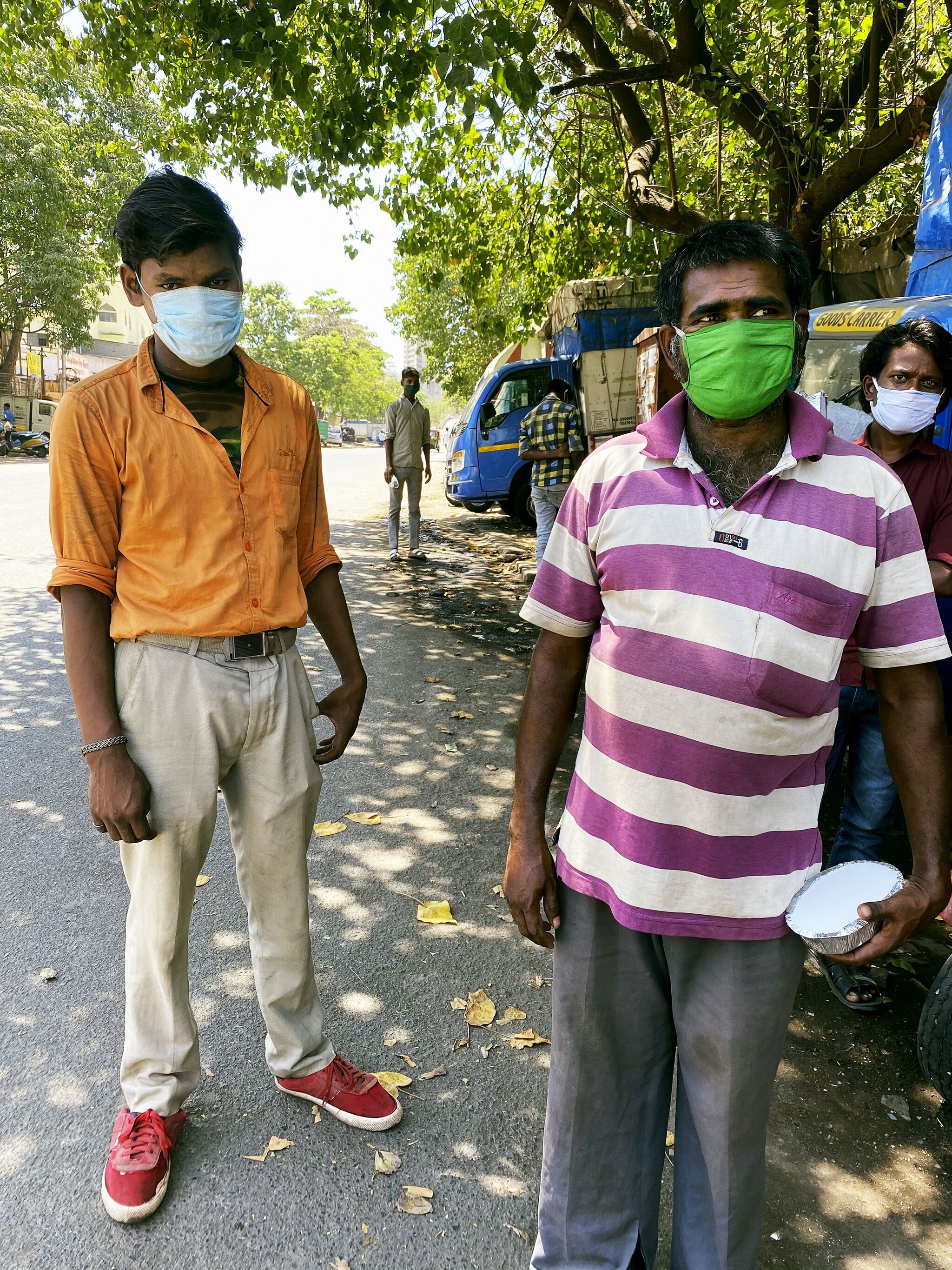

The home ministry on April 30 allowed the inter-state movement of migrants by road. The migrant workforce is estimated to comprise a fifth of India’s total workforce. Most of them are from UP, Bihar, Odisha, Bengal, Jharkhand and Madhya Pradesh. Construction worker Ram Roop Sahani from Uttar Pradesh (right) and a co-worker are stranded in suburban Mulund in Mumbai. Their food requirements are met by local residents

Construction worker Ram Roop Sahani from Uttar Pradesh (right) and a co-worker are stranded in suburban Mulund in Mumbai. Their food requirements are met by local residents

Image: Pooja Sarkar

“Migrant labourers have been subjected to extraordinary hardship. They have been deprived of their livelihoods and the comfort of their homes. The first objective should be to take these labourers back home,” says Mahesh Vyas, managing director and CEO of Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy Pvt Ltd (CMIE).

According to a report by the International Labour Organization on April 29, as a result of the economic crisis created by the pandemic, almost 1.6 billion informal economy workers out of a worldwide total of 2 billion, and a global workforce of 3.3 billion, have suffered massive damage to their capacity to earn a living.

The first month of the crisis is estimated to have resulted in a drop of 60 percent in the income of informal workers globally. This translates to a reduction of 81 percent in Africa and the Americas, 21.6 percent in Asia and the Pacific, and 70 percent in Europe and Central Asia.

Closer home, CMIE said the labour participation rate fell to an all-time low in March, the unemployment rate shot up sharply and the employment rate fell to an all-time low of 38.2 percent. The fall since January is particularly steep.

“If you have less labour than what you require, the demand-supply chain is under pressure. But we need to take into cognisance that we treat them as second-class citizens when they are an integral part of society… they need to be given that respect,” says Vyas.

According to the 2011 Census, 300 million people migrated to India, especially women, due to marriage. Outside migration because of marriage, nearly 50 million people migrated internally in the country due to economic reasons and 10 million people moved towards the city centres for educational purposes.

Chinmay Tumbe, professor at the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, who has authored a book on migration in India called India Moving, says, “The Economic Survey of 2016-17 has a chapter on migration if you look at Census numbers, they tell you that 55 million people had reported that they are moving for economic reasons, but that report puts the number at upward of 100 million people… that tells you about the serious underestimation.”

In his book, Tumbe explains seasonal migration is when people move away from their homes for a few months every now and then, with each spell not lasting more than six months.

Sahani, for instance, lives on construction sites and goes back home during the harvest season to help his family with farming activities. There are 146 million land holdings in India as per the 2015-16 Agricultural Census, of which 70 million (48 percent) are less than half a hectare. So, farming only provides subsistence levels of existence. “You can improve the situation of farmers, but you cannot make them prosperous in 10-20 years, taking about half of the current agriculture workforce out of this occupation,” says economist Arvind Panagariya.

This explains why daily wage workers are forced to go back to the cities in search of work. They usually move with their families, live in makeshift tents by the roadside with the constant threat of eviction or share a dingy room with scores of others.

As part of the government’s relief measures, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman announced that under the PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana, additional 5 kg rice or wheat per household will be provided for three months and 1 kg of pulses per family. This will be beneficial to 80 crore people. The government also said workers should be paid their wages during the lockdown, rents should be waived off and labourers should be allowed to work for 12 hours instead of eight.

Some economists believe this is the right time for India to start a discussion on Universal Basic Income. “Particularly concerned in case of India… I think we need social state and social policy laws,” says French economist Thomas Piketty.

“If you don’t have a particular safety net and some minimum income so that poor people don’t have to go out all the time to get work, that’s not going to work.”

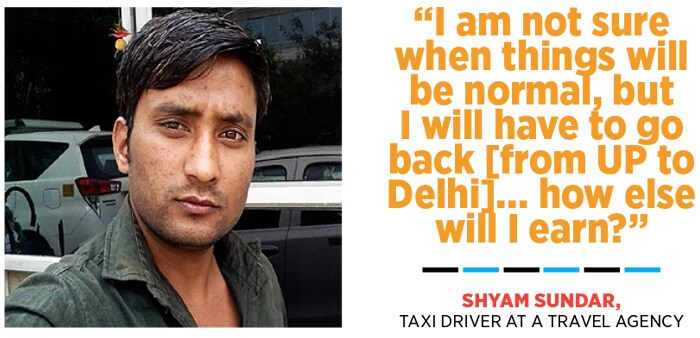

While many migrants still await the journey back home, some others like Shyam Sundar are lucky. The 27-year-old works as a taxi driver for a travel agency in Gurugram and lived in the capital for the last six years. It took him two days to return to his home in Barsana village near Mathura in UP, nearly 148 km from Delhi.

“I walked for a few kilometres and then my friend and me travelled by truck. After covering some distance, we boarded a tanker and then another truck to reach home,” says Sundar. He is the sole bread earner of his family comprising his parents, four siblings, wife and two children, and earns Rs 14,000 a month. He is yet to get relief money from the government and says he is dependent on his little farm for basic survival. “I am not sure when things will be normal, but I will have to go back… how else will I earn?” he says.

First Published: May 05, 2020, 18:13

Subscribe Now