A lot has changed since.

Today, Byju’s is one of the largest edtech players globally, with a valuation of a little over $13 billion. So far, it has received funding of $2.3 billion from investors including Tiger Investments, Baron Capital, Owl Ventures and BlackRock. On March 31, Byju’s raised another $460 million as part of its ongoing series F round, led by MC Global Edtech Investment Holdings LP, with participation from Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin’s B Capital, among other investors.

With funding flowing in, Byju’s has also been on an acquisition spree—starting with Osmo in 2019, followed by online coding startup White Hat Jr last August for $300 million, making it one of the biggest deals in the Edtech space. It also bought virtual simulations startup LabInApp last September. According to Tracxn, Byju’s has acquired 11 companies worth $1.43 billion (as of February 2021). “The vision for most of these entrepreneurs is to try and get as many products out and get access to a larger platform. We have been able to scale these businesses by giving our full support, but also giving them the autonomy to run the company freely,” says Kishore, chief strategy officer at Byju’s. In the first 2.5 years since Byju’s launched its app, it saw about 45 million downloads since the Covid-19 pandemic began, there has been another 40 million. ![anita kishore anita kishore]() Anita Kishore, Chief strategy officer, Byju"s

Anita Kishore, Chief strategy officer, Byju"s

Image: Nishant Ratnakar

Then there’s Unacademy that has acquired six startups—Kreatryx, CodeChef, PrepLadder, Mastree, Coursavy and NeoStencil—in various sectors, in 2020 alone. The latest is Handa ka Funda, which it acquired for an undisclosed amount in March 2021. Unacademy’s valuation has increased 4x, from $510 million to $2 billion between February and November 2020. Its total funding is more than $400 million, including investors like Tiger Global Management, Dragoneer Investment Group and Sequoia Capital. When it comes to acquiring companies, Hemesh Singh, co-founder and CTO, Unacademy says, “Our focus is on companies that use technology in the education space in interesting ways. Also, having a good relationship and alignment with the founders is necessary.” So far, Unacademy has been focusing on prep for competitive exams, including the likes of JEE, UPSC and NEET. But from the second half of 2020, they have started looking at the K-12 segment as well.![edtech opportunity edtech opportunity]() Over the next three to five years, there is going to be a lot of consolidation in the online education space. “I feel that across three segments in edtech—K-12, test prep and working professionals—there’s going to be one to two large players in each segment. Education is not going to be like one-player-takes-all kind of a market. There will be one player holding maybe 40 percent market share, another holding 30 percent, and the last 30 percent will be owned by multiple players,” says Mayank Kumar, managing director of upGrad.

Over the next three to five years, there is going to be a lot of consolidation in the online education space. “I feel that across three segments in edtech—K-12, test prep and working professionals—there’s going to be one to two large players in each segment. Education is not going to be like one-player-takes-all kind of a market. There will be one player holding maybe 40 percent market share, another holding 30 percent, and the last 30 percent will be owned by multiple players,” says Mayank Kumar, managing director of upGrad.

Unlike a lot of other players in this space, online higher education company upGrad has not seen an exponential jump in growth—it has been consistently growing at about 100 percent year-on-year—since it focuses on working professionals. Kumar believes, “In the longer run, there will be consolidation, and the pace of acquisition will also increase. The two or three larger players are likely to acquire multiple companies, and the large players will be ‘large’ because of mergers and acquisitions.”![hemesh singh hemesh singh]() Hemesh Singh, Co-founder & CTO, UnacademyWith two giants emerging, what is the future for smaller players: Stay niche or get gobbled up? Sajith Pai, director at Blume Ventures, one of the largest investors in this space, says, “These two—consolidation and the arrival of new innovative players—will keep going hand in hand.”

Hemesh Singh, Co-founder & CTO, UnacademyWith two giants emerging, what is the future for smaller players: Stay niche or get gobbled up? Sajith Pai, director at Blume Ventures, one of the largest investors in this space, says, “These two—consolidation and the arrival of new innovative players—will keep going hand in hand.”

*****

So far Byju’s has focussed on an asynchronous app-based approach, where content is available for students to access at any time. The acquisition of White Hat Jr was to help the company move into a synchronous format and build its one-on-one live tutoring model. “White Hat Jr has done a great job in scaling this model, with over 10,000 teachers, while still maintaining an average session rating of 4.85/5,” says Byju’s Kishore. Its live tutoring model will have an India presence, but will be focussed on international markets.![mayank kumar mayank kumar]() Mayank Kumar, Co-Founder & MD, upGrad“The Byju’s acquisition was a critical step in our journey and helped us fast-track the growth initiatives. Today, WhiteHat Jr is present in multiple countries globally, and has already expanded its product offering to two subjects—coding and maths,” says Karan Bajaj, founder and CEO, WhiteHat Jr. The platform has more than 9 million registered students, of which 1.75 lakh are paying subscribers.

Mayank Kumar, Co-Founder & MD, upGrad“The Byju’s acquisition was a critical step in our journey and helped us fast-track the growth initiatives. Today, WhiteHat Jr is present in multiple countries globally, and has already expanded its product offering to two subjects—coding and maths,” says Karan Bajaj, founder and CEO, WhiteHat Jr. The platform has more than 9 million registered students, of which 1.75 lakh are paying subscribers.

Test preparation for K-12 is another vertical that Byju’s is betting on big time in the hybrid space. This makes sense given the company is acquiring exam preparation firm Aakash Educational Services (AESL) in a deal reportedly worth $900 million (as on April 5, 2021), making it the highest valued deal in the edtech space till now.

![k-12 learning k-12 learning]()

“When AESL, which is a well known name in test preparation, joins hands with large players in edtech like Byju’s, we can provide better access of test preparation education to Indian aspirants. The number of students who write test prep for medical and IIT in India are close to around 2 million,” says Aakash Chaudhry, managing director, AESL.

Blackstone-backed AESL has a pan-India network of over 205 Aakash centres (including franchises) and a student count of more than 250,000. In June 2020, in the midst of the pandemic, AESL transferred a section of its offline classes to the Aakash digital app. “Our online education has grown more than 100 percent this year. The number of students has increased by 150 to 200 percent, and we have doubled in terms of revenues. There is a great acceptance that we are experienced from the test prep side. 2020 has been our best result year in 33 years,” adds Chaudhry.

Another likely acquisition in this space is rival Toppr. Launched in 2014, Toppr provides free resources in the form of video lectures, revision tips and artificial intelligence (AI)-enabled instant answers to doubts. “In 12 months, our traffic grew 9x, which has sustained even as schools have partially opened now. I think this is a permanent behavioural shift, as students and parents have discovered the value that edtech can provide in learning,” says Joe Kochitty, senior vice president, products, Toppr. Byju’s is reportedly in advanced talks to acquire Toppr for $150-160 million. Toppr declined to comment on any acquisition-related query.

When Unacademy was launched in 2015, creating educational content by using technology was tough, so it started by focussing on recorded content and creating tools for educators to create content. However, recently, the startup has decided to shift focus. “We are now seeing a lot of interest in the live learning space,” says Singh of Unacademy. Live tutoring has also been a trend mirrored by other edtech players, including Byju’s.

As one of the largest players in the space, there are some advantages that come with scale. Singh explains, “Compared to where we were two or three years ago, we can now run more experiments and innovate faster. When we see something working well, we can double down faster.”

Up until two years ago, convincing parents to let children use edtech platforms was a challenge, recalls Vamsi Krishna, CEO and co-founder of Vedantu. “It was an alien concept. When we spoke to parents about Vedantu, the first question they would ask is: How can studying happen online?” As teachers themselves, the founders—Krishna, Pulkit Jain, co-founder and products head, and Anand Prakash, co-founder and head of academics—saw a lot of potential with live tutoring. “We really feel that the interaction is as critical as the content,” says Krishna. When Vedantu started, internet was at 2G and 3G, while 4G was just coming in. Since then, internet penetration has grown by leaps and bounds. Covid-19 has only accelerated Vedantu’s growth from 2.5-3x year-on-year pre-Covid to 7x now, with a 180 percent increase in overall user base.

India is now witnessing the second wave of the pandemic, but with vaccination programmes in progress, will this growth in the edtech sector sustain post the pandemic? “Definitely. The value in getting access to the best education while sitting at home, and teaching from the convenience of your home is big enough for a lot of learners and educators to continue preferring online learning and teaching,” says Singh of Unacademy.

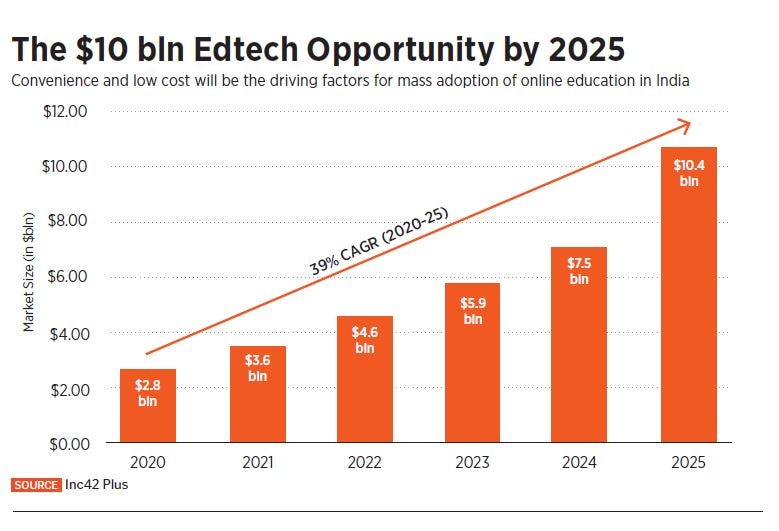

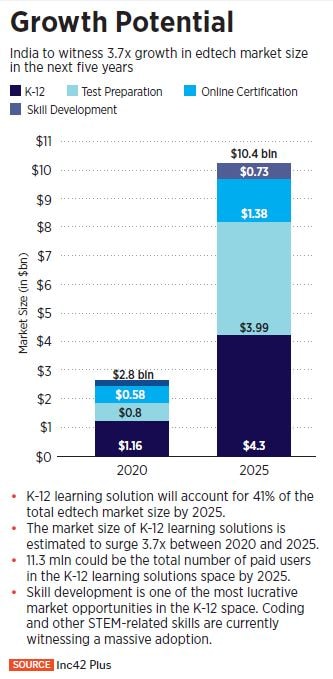

Within the edtech space, especially in the last year, experts believe there has been a breakout of a handful of players and the rest have either been consolidated or have lost the plot. “None of the new companies are coming into the full-stack segment, but rather finding particular niche segments for themselves, simply because the gap between the small and large players is huge,” says Krishna of Vedantu. The size of India’s edtech market is estimated to grow nearly four-fold over the next five years, from the current $2.8 billion to $10.4 billion in 2025, according to a recent report by Inc42 Plus. As of 2020, there are 4,450 startups in the sector and evidently there is space for smaller niche players to enter as well.

*****

The astronomical rise of edtech in India has enabled students to access quality education at an affordable price. The online education market for classes 1-12 is estimated to increase 6.3 times in the next one year and create a $1.7 billion market. The post K-12 market is set to grow 3.7 times to touch $1.8 billion, as per a report by RedSeer and Omidyar Network India.![vamsi krishna vamsi krishna]() Vamsi Krishna_CEO & Co-founder, Vedantu

Vamsi Krishna_CEO & Co-founder, Vedantu

The onset of the pandemic has also forced professionals to utilise their time by upskilling and learning online to perform better in their current jobs or find better ones. Bengaluru-based Simplilearn, an online bootcamp for digital skills training, saw a 100 percent growth in enrolments in the past few months. “Over the last six months, we also on-boarded over 50,000 corporate learners across 12 countries and witnessed several Indian startups and leading universities partner with us for tech-specific skilling programmes,” says Krishna Kumar, CEO and founder of Simplilearn. The startup has helped more than 2,000,000 professionals and 2,000 companies across 150 countries.

There’s another edtech startup that is looking to fill the skill gap among job aspirants, albeit with a different model. Founded in 2019, Masai School aids tech aspirants bridge the skill gap, and helps them use latest technologies. After clearing the in-house entrance exam, the selected students go through a seven-month bootcamp, where they are taught the basics of coding as well as trained to develop an app. The interesting part is the startup follows a ‘Study Now and Pay Later’ approach, and charges the students after they have received their first pay cheque of ₹5 lakh per annum or above. Despite the pandemic last year, “The third batch of Masai School that started in October 2019 and graduated in April 2020, saw a placement percentage of 86.1, with the highest salary going up to ₹9 lakh per annum,” says Prateek Shukla, co-founder and CEO. The company claims that the number of students who were enrolled in Masai School over the last three months is equivalent to the total number of students enrolled since its inception. “By FY22, we are positive about helping about 2,500 graduates, a 10x jump from our existing numbers,” adds Shukla.

Unlike the mainstream players, there are some who are finding their niche within the vernacular space, by taking into account the regional differences while implementing solutions. One such startup is Kochi-based Entri, founded in 2017 by Mohammed Hisamuddin and Rahul Ramesh. “We figured out early that when users learn in their mother tongue, they grasp it better even if they understand English. We capitalised on this opportunity and have been able to grow by providing courses in local languages,” says Hisamuddin. Entri is a learning app for job aspirants in India. It provides content such as mock and adaptive tests, video lessons and more in local languages. In the last 12 months, the company claims to have grown from $700,000 annual recurring revenue (ARR) to $3.5 million ARR. User registrations have grown from 1.5 million to 5 million, and it has added more than 130,000 paid subscribers. “The kind of edtech adoption that we saw during the six months of the lockdown would have otherwise taken six years to happen,” he adds.

Although a lot of training centres had to remain shut during the lockdown, the founders of brick-and-mortar Ludhiana-based training centre Edusquare saw the pandemic as an opportunity to scale up their business.

They had launched YSchool in 2020 as an alternative mode of teaching, combining edtech with physical coaching centres. The YSchool learning app provides solutions for students between classes 9 and 12 to crack competitive exams. “We have gone from 0 to 80,000 users in 10 months during the pandemic for our app and online product. We aim to have 1 million subscribers by 2022,” says Anand Arora, CEO, YSchool.

When it comes to early childhood learning, startup Square Panda India has been working with the government of India on an early learning initiative, ‘Aarambh’, to develop the Early Childhood Education and Care (ECCE) ecosystem in every state. “We are working with central and multiple state governments, schools, communities, and impact organisations to prove Aarambh’s efficacy, effecting change in educators and young students across India’s grassroots through technologies like AI and machine learning. Our projects across states like Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh had overwhelming responses,” says Ashish Jhalani, MD, Square Panda India. The programme, says Jhalani, will empower all stakeholders, from anganwadi workers and educators, to children. For instance, Square Panda’s AI-enabled chatbot, SquareTalk, assists early years’ educators and provides learning resources.

The sector has also seen increased investor activity due to the remarkable growth potential of players. Last year, the edtech sector saw an investment of $2.1 billion compared to $1.7 billion in the entire previous decade, according to a report on the e-learning industry by Anand Rathi Advisors Limited.

The industry is going through an exciting phase, with the behaviour change towards online learning expected to continue in 2021 and beyond, says Siddharth Nautiyal, partner, Omidyar Network India. “In the last one year, we have backed several new companies in the sector, including Kutuki, Masai and Uolo. The acceleration in 2020 has advanced growth for edtech companies by three to five years compared to their original plan.”

However, education globally is still one of the most under-invested sectors. It took a pandemic to catalyse the growth, and for many stakeholders—from teachers to students—to try edtech for the first time, something that would have taken four to five years otherwise.

Newer players are entering since the entry barrier in education is not that high.

Pai of Blume Ventures adds, “There will always be new founders emerging with exciting new solutions and approaches to new and old problems. Meanwhile, of course, there will be some consolidation as top companies start acquiring and giving exits to smaller companies. But both will coexist.”

Illustration: Sameer Pawar [br]

Illustration: Sameer Pawar [br] Anita Kishore, Chief strategy officer, Byju"s

Anita Kishore, Chief strategy officer, Byju"s Over the next three to five years, there is going to be a lot of consolidation in the online education space. “I feel that across three segments in edtech—K-12, test prep and working professionals—there’s going to be one to two large players in each segment. Education is not going to be like one-player-takes-all kind of a market. There will be one player holding maybe 40 percent market share, another holding 30 percent, and the last 30 percent will be owned by multiple players,” says Mayank Kumar, managing director of upGrad.

Over the next three to five years, there is going to be a lot of consolidation in the online education space. “I feel that across three segments in edtech—K-12, test prep and working professionals—there’s going to be one to two large players in each segment. Education is not going to be like one-player-takes-all kind of a market. There will be one player holding maybe 40 percent market share, another holding 30 percent, and the last 30 percent will be owned by multiple players,” says Mayank Kumar, managing director of upGrad. Hemesh Singh, Co-founder & CTO, UnacademyWith two giants emerging, what is the future for smaller players: Stay niche or get gobbled up? Sajith Pai, director at Blume Ventures, one of the largest investors in this space, says, “These two—consolidation and the arrival of new innovative players—will keep going hand in hand.”

Hemesh Singh, Co-founder & CTO, UnacademyWith two giants emerging, what is the future for smaller players: Stay niche or get gobbled up? Sajith Pai, director at Blume Ventures, one of the largest investors in this space, says, “These two—consolidation and the arrival of new innovative players—will keep going hand in hand.” Mayank Kumar, Co-Founder & MD, upGrad“The Byju’s acquisition was a critical step in our journey and helped us fast-track the growth initiatives. Today, WhiteHat Jr is present in multiple countries globally, and has already expanded its product offering to two subjects—coding and maths,” says Karan Bajaj, founder and CEO, WhiteHat Jr. The platform has more than 9 million registered students, of which 1.75 lakh are paying subscribers.

Mayank Kumar, Co-Founder & MD, upGrad“The Byju’s acquisition was a critical step in our journey and helped us fast-track the growth initiatives. Today, WhiteHat Jr is present in multiple countries globally, and has already expanded its product offering to two subjects—coding and maths,” says Karan Bajaj, founder and CEO, WhiteHat Jr. The platform has more than 9 million registered students, of which 1.75 lakh are paying subscribers.

Vamsi Krishna_CEO & Co-founder, Vedantu

Vamsi Krishna_CEO & Co-founder, Vedantu