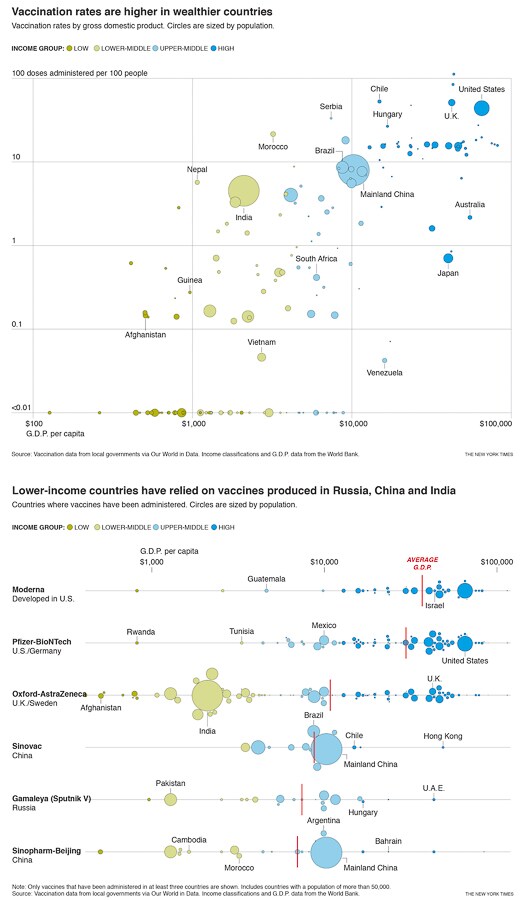

Well over three-quarters of the more than half-billion vaccine doses that have been administered have been used by the world’s richest countries. The reason, experts say, lies in how — and when — deals for doses were struck.

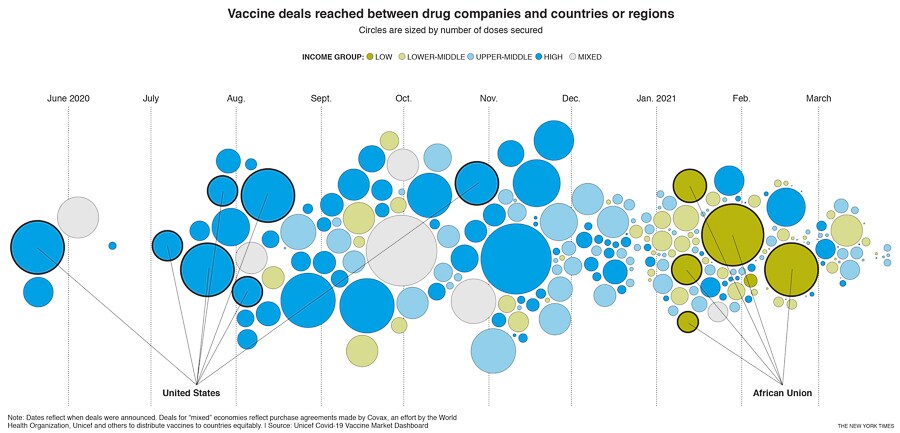

In the early days of the pandemic, when drugmakers were just starting to develop vaccines, placing orders for any of them was a risk. Wealthier countries could mitigate that risk by placing orders for multiple vaccines and, by doing so, tied up doses that smaller countries may have otherwise purchased, according to experts.

As a result, most higher-income countries were able to pre-order enough vaccines to cover their populations several times over, while others had trouble securing any doses at all. Throughout 2020, even middle-income countries had trouble winning contracts.

“We saw it with countries like Peru and Mexico,” said Andrea Taylor, a researcher at Duke University who is studying the vaccine purchase agreements. “Money wasn’t the problem for them. They have the financing to make the purchases, but they couldn’t get to the front of the line.”

Low-income countries made their first significant vaccine purchase agreements in January 2021 — eight months after the United States and the United Kingdom made their first deals, according to data compiled by UNICEF.

The result has been that, as of March 30, 86% of shots that have gone into arms worldwide have been administered in high- and upper-middle-income countries. Only 0.1% of doses have been administered in low-income countries.

“Inequities are growing, unfortunately,” Taylor said, “and we expect that to be the case for at least the next six months while wealthy countries continue to keep the majority of doses rolling off production lines.”

![wealthy countries vaccines 2-bg wealthy countries vaccines 2-bg]()

COVAX, a global effort to distribute vaccines equally that is run by the World Health Organization and others, has tried to alleviate some of the imbalances. Its primary goal is to provide vaccines to 92 lower-income countries, through its program called Advanced Market Commitment, or AMC. Those vaccines are paid for with cash donations by governments and organizations the United States has donated $2.5 billion, for example, and Germany has donated $1.1 billion.

For countries that can afford their own vaccines, COVAX has also offered a way to buy doses without jumping ahead in line, by acting as an intermediary between those countries and drug companies. As an incentive, COVAX prenegotiated agreements that any of its member countries could use, leveraging its ability to place bigger orders earlier in the pandemic. In turn, the countries that bought vaccines through those deals would wait their turn, and get their doses no sooner than lower-income countries.

As of March 30, COVAX has shipped 32.9 million vaccine doses to 70 countries and regions. Most of those shipments were donations to lower-income countries. To put that number in context, it is just 6% of the 564 million doses that have been administered worldwide.

The World Health Organization expects that supply to increase, however. According to a budget released last month, the organization said COVAX was “on track to hit its target of supplying at least 2 billion vaccine doses in 2021.” And 1.3 billion of those doses, the budget said, would be donations to lower-income countries.

Even with that influx, however, poor countries may end up waiting years before their populations can be fully vaccinated. Kenya, for example, expects that by 2023 it will have just 30% of its population vaccinated, and that’s with COVAX covering the first 20%. That long wait would give the virus more time to spread, and potentially give rise to new mutations.

The global race for doses has also affected which countries get which vaccines. With much of the supply of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines already spoken for by wealthier countries, China, India and Russia have become important suppliers of vaccines to lower-income countries. And some experts believe those governments can use such relationships to exert soft power.

![wealthy countries vaccines 1-bg wealthy countries vaccines 1-bg]()

“To empower other nations with vaccine access is a powerful tool that can wield considerable influence,” said Dania Thafer, the executive director of the Gulf International Forum, a Washington-based think tank.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine has become ubiquitous: At least 94 countries of varying income levels have administered doses. Its lower price and comparatively easy storage positioned it as a crucial part of the global vaccination effort, but it has recently suffered a series of setbacks.

A study found that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine showed relatively low efficacy in preventing mild and moderate cases of the more contagious variant that’s dominant in South Africa, leading the South African government to suspend its rollout.

Some European countries suspended the use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine in mid-March because of concerns it might increase the risk of blood clots. A review by the European Medicines Agency later found the vaccine to be “safe and effective,” with no overall increase in the risk of clots, but the confusion has seen public confidence in the vaccine plummet.

India has clamped down on exports of the vaccine manufactured at the Serum Institute of India, one of the world’s largest vaccine producers, while the country battles its own worsening outbreak. Many low-income countries are dependent on exports from the Serum Institute, including Nepal, which has already halted its vaccination campaign because of shortages.

In a joint statement released Tuesday, more than two dozen heads of government and international agencies called for “a new international treaty for pandemic preparedness and response.” They stressed the importance of a coordinated approach to future pandemics, including with vaccination efforts.

“Immunization is a global public good, and we will need to be able to develop, manufacture and deploy vaccines as quickly as possible,” the statement said.Well over three-quarters of the more than half-billion vaccine doses that have been administered have been used by the world’s richest countries. The reason, experts say, lies in how — and when — deals for doses were struck.

In the early days of the pandemic, when drugmakers were just starting to develop vaccines, placing orders for any of them was a risk. Wealthier countries could mitigate that risk by placing orders for multiple vaccines and, by doing so, tied up doses that smaller countries may have otherwise purchased, according to experts.

As a result, most higher-income countries were able to pre-order enough vaccines to cover their populations several times over, while others had trouble securing any doses at all. Throughout 2020, even middle-income countries had trouble winning contracts.

“We saw it with countries like Peru and Mexico,” said Andrea Taylor, a researcher at Duke University who is studying the vaccine purchase agreements. “Money wasn’t the problem for them. They have the financing to make the purchases, but they couldn’t get to the front of the line.”

Low-income countries made their first significant vaccine purchase agreements in January 2021 — eight months after the United States and the United Kingdom made their first deals, according to data compiled by UNICEF.

The result has been that, as of March 30, 86% of shots that have gone into arms worldwide have been administered in high- and upper-middle-income countries. Only 0.1% of doses have been administered in low-income countries.

“Inequities are growing, unfortunately,” Taylor said, “and we expect that to be the case for at least the next six months while wealthy countries continue to keep the majority of doses rolling off production lines.”

COVAX, a global effort to distribute vaccines equally that is run by the World Health Organization and others, has tried to alleviate some of the imbalances. Its primary goal is to provide vaccines to 92 lower-income countries, through its program called Advanced Market Commitment, or AMC. Those vaccines are paid for with cash donations by governments and organizations the United States has donated $2.5 billion, for example, and Germany has donated $1.1 billion.

For countries that can afford their own vaccines, COVAX has also offered a way to buy doses without jumping ahead in line, by acting as an intermediary between those countries and drug companies. As an incentive, COVAX prenegotiated agreements that any of its member countries could use, leveraging its ability to place bigger orders earlier in the pandemic. In turn, the countries that bought vaccines through those deals would wait their turn, and get their doses no sooner than lower-income countries.

As of March 30, COVAX has shipped 32.9 million vaccine doses to 70 countries and regions. Most of those shipments were donations to lower-income countries. To put that number in context, it is just 6% of the 564 million doses that have been administered worldwide.

The World Health Organization expects that supply to increase, however. According to a budget released last month, the organization said COVAX was “on track to hit its target of supplying at least 2 billion vaccine doses in 2021.” And 1.3 billion of those doses, the budget said, would be donations to lower-income countries.

Even with that influx, however, poor countries may end up waiting years before their populations can be fully vaccinated. Kenya, for example, expects that by 2023 it will have just 30% of its population vaccinated, and that’s with COVAX covering the first 20%. That long wait would give the virus more time to spread, and potentially give rise to new mutations.

The global race for doses has also affected which countries get which vaccines. With much of the supply of the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines already spoken for by wealthier countries, China, India and Russia have become important suppliers of vaccines to lower-income countries. And some experts believe those governments can use such relationships to exert soft power.

“To empower other nations with vaccine access is a powerful tool that can wield considerable influence,” said Dania Thafer, the executive director of the Gulf International Forum, a Washington-based think tank.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine has become ubiquitous: At least 94 countries of varying income levels have administered doses. Its lower price and comparatively easy storage positioned it as a crucial part of the global vaccination effort, but it has recently suffered a series of setbacks.

A study found that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine showed relatively low efficacy in preventing mild and moderate cases of the more contagious variant that’s dominant in South Africa, leading the South African government to suspend its rollout.

(BEGIN OPTIONAL TRIM.)

Some European countries suspended the use of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine in mid-March because of concerns it might increase the risk of blood clots. A review by the European Medicines Agency later found the vaccine to be “safe and effective,” with no overall increase in the risk of clots, but the confusion has seen public confidence in the vaccine plummet.

India has clamped down on exports of the vaccine manufactured at the Serum Institute of India, one of the world’s largest vaccine producers, while the country battles its own worsening outbreak. Many low-income countries are dependent on exports from the Serum Institute, including Nepal, which has already halted its vaccination campaign because of shortages.

(END OPTIONAL TRIM.)

In a joint statement released Tuesday, more than two dozen heads of government and international agencies called for “a new international treaty for pandemic preparedness and response.” They stressed the importance of a coordinated approach to future pandemics, including with vaccination efforts.

“Immunization is a global public good, and we will need to be able to develop, manufacture and deploy vaccines as quickly as possible,” the statement said.