Designing A Service Outsourcing Process

In an ideal world, the client’s objective is to design an outsourcing process that not only results in the selection of the right provider, but also ensures that the information rent is not substantia

Over the last decade, external partners have been increasingly charged with delivering a wide range of corporate business processes. Once restricted to contract manufacturing, corporations today outsource processes ranging from IT support, transactions and customer care (known as BPO) to knowledge-based activities (KPO) such as R&D. As a result of this trend, the global BPO expenditure was estimated to be about $153 billion in 2011.

BPO/KPO has become a truly “global” phenomenon. Thus it is important for corporations to hone a range of cross-cultural skills in order to work with external partners from various continenets with different cultures and legal contexts, speak different languages, and leverage a global resource pool that provides deep expertise along with the significant cost advantages that result from increasing competition.

The core to success: provider selection and contract effectiveness.

The success of any outsourcing initiative depends on two important factors: with whom the client firm collaborates (provider selection), and how it structures the outsourcing contract. The client typically shortlists a set of potential providers through a formal request-for-information (RFI) process coupled with secondary research and industry opinion. However, ensuring a shortlisted provider has capabilities that appropriately match most of the client’s requirements is challenging due to the client’s business context and the nature of its processes. In fact, our research in Europe shows that process outsourcing projects are more than twice as likely to fail when the provider does not have client-specific capabilities,.

At the same time, structuring an effective outsourcing contract is in no way a trivial exercise – it requires a good understanding of the provider’s capabilities as well as close alignment of client-provider incentives. Both academic research and practitioner experience indicates that poorly designed contracts often result in inequitable allocation of the contract value created for the client, i.e., disproportionate “information rent” extracted by the vendor. In fact, according to a survey by ISG, outsourcing contracts typically deliver 28% less value than originally anticipated. In an ideal world, the client’s objective is to design an outsourcing process that not only results in the selection of the right provider, but also ensures that the information rent is not substantial.

The contracting conundrum

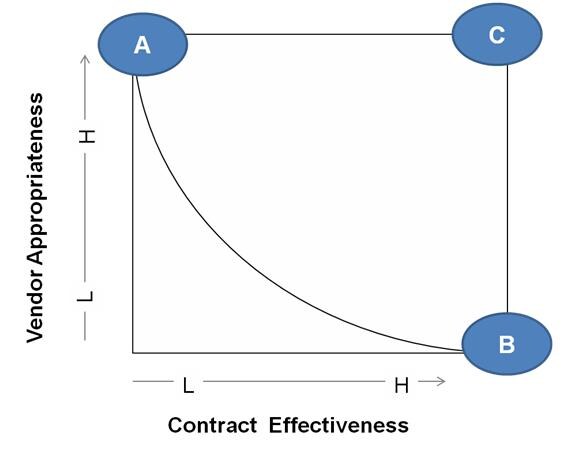

Based on our research, we find that it is not feasible for the client to attain both these objectives simultaneously, i.e., point C in Figure 1. On one end of the spectrum, the client can usually implement a process that improves its chances of good provider selection, but such a process often leads to a suboptimal contract structuring (point A in Figure 1). On the other end of the spectrum we find that, the client can implement a process that attains high contract effectiveness (low information rent for the vendor point B in Figure 1), but here the client is not guaranteed good provider selection. Figure 1

Figure 1

Good selection is attained by an outsourcing process that incentivizes the shortlisted providers to “truthfully” reveal their capabilities. The client can do this by inviting bids from providers in the form of a reverse auction--a process where bidders bid for the right to supply the required service at a specified service level. The client then thoroughly evaluates the bids to select a preferred provider whose bid becomes the basis of a contractual agreement between the two parties. This process helps surface providers that are more capable of delivering superior outcomes by outbidding others, resulting in “truthful revelation” for the client. However, a more capable provider’s bidding strategy is to only marginally outbid other providers in order to enjoy a surplus of information rent. In other words, the client must sacrifice some profit margin to secure a capable collaborator through a competitive bidding process.

By contrast, if the client’s primary objective is contract effectiveness, then, unlike the bidding process, the client should structure the contract via a comprehensive contract negotiation process. However, the client must select a provider before it can enter into the contract negotiation process. This process does not incentivize the providers to truthfully reveal their capabilities and promised outcomes during selection since they anticipate a rigorous post-selection negotiation process, all vendors “signal” enhanced capabilities, over-promising on outcomes for the client. Therefore, the client using such an outsourcing process cannot differentiate between the shortlisted providers, leading to sub-optimal selection. In game theory, such an outcome is often called as an uninformative equilibrium in a game with cheap-talk.

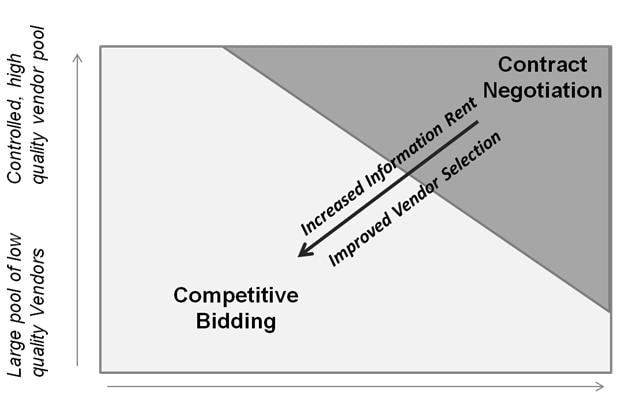

These two types of outsourcing approaches create a conundrum for client firms undertaking outsourcing initiatives. We call this trade-off as the contracting conundrum: provider appropriateness or contract effectiveness? When designing the outsourcing process, client personnel should be aware of the underlying trade-offs to ensure that they architect the optimal process. We find that clients outsourcing more standard processes tend to align themselves closer to point A in our framework, whereas clients that outsource more specialized/customized processes tend to align closer to point B. We find that when the information rent can be high due to the customized nature of the service process and when provider selection is not critical due to high average provider quality in the market, the outsourcing approach of selection followed by contract negotiation is preferred over competitive bidding and vice versa. These findings are illustrated in Figure 2. Figure 2

Figure 2

So how can a client escape the contracting conundrum and get to point C in our framework? One strategy is to retain full negotiation flexibility. Under this approach, the client engages one provider in contract negotiation, and if, during negotiation, it is found that the provider’s capabilities do not fulfill the client’s requirements, then the client can switch to another provider and conduct a new round of contract negotiations. Such an approach allows the client to reduce the information rent earned by the selected provider, and also provide sufficient flexibility to contract with a provider that is most capable of delivering its requirements. However, it is important to note that this approach may result in significant additional costs due to switching between providers during the contract negotiation stage.

Conclusion

Our research indicates that provider selection and contracting is a complex, interlinked, multistage process. Therefore, designing the right outsourcing process is key for clients that want to ensure a successful outsourcing initiative. Insights from our research suggest that a client cannot obtain good provider selection and contract effectiveness simultaneously, unless they eliminate the contracting conundrum. Client firms must evaluate their priorities and align themselves along one dimension of this trade-off. However, if the client is able eliminate the contracting conundrum and obtain a good selection process and effective contracting simultaneously, it will add significant expenses as a result of the costs associated with switching between providers, and hence a trade-off is inevitable. Understanding it is the only way to be able to design an optimal outsourcing process.

First Published: Dec 19, 2012, 06:39

Subscribe Now