IT's time to make hay

Despite a wobbly outsourcing industry, a stronger American market has helped tech firms grow, and has pushed two software billionaires up the ranks. But Infosys co-founders miss out as stocks tumbled

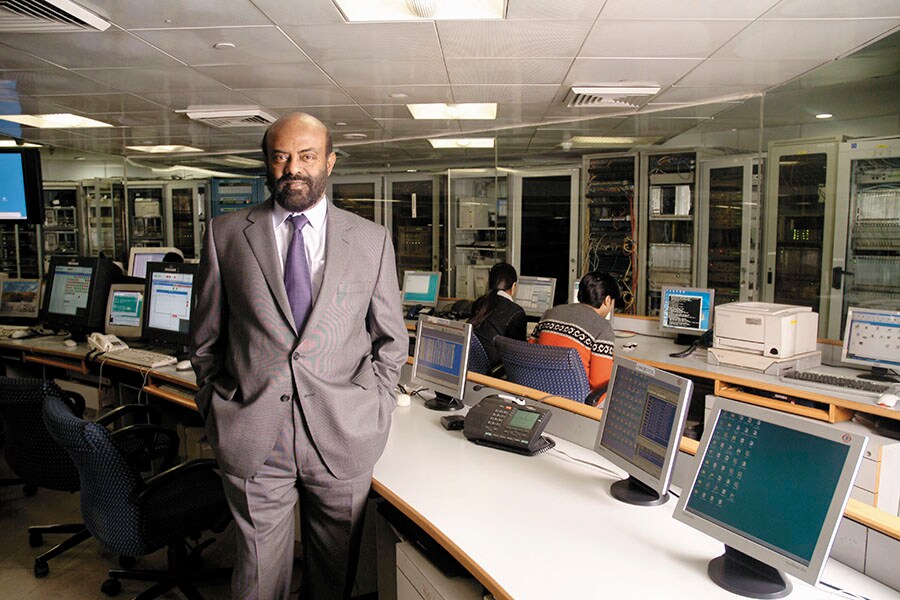

Shiv Nadar of HCL Technologies has seen his wealth increase to $13.4 billion

Shiv Nadar of HCL Technologies has seen his wealth increase to $13.4 billion

Image: Ritesh Sharma / The India Today Group / Getty Image

The wealth of IT billionaires, much of which is derived from the value of their stocks in the companies they founded, is under threat in the long run as outsourcing, the job that built their wealth, is fast becoming obsolete. But the year under consideration for the 2017 Forbes India Rich List has revealed a contrarian trend in which the fortunes and the ranks of IT czars have gone up.

HCL Technologies’ Shiv Nadar has moved up a spot to No 7 this year, while his wealth has increased almost by a fifth to $13.4 billion, helped by a nearly 10 percent increase in HCL’s stock price in the 12 months through the September quarter. His Bengaluru rival Azim Premji has climbed two spots to No 2, behind Mukesh Ambani of Reliance Industries (Reliance Industries owns Network 18, the publishers of Forbes India). Premji, who owns close to three-quarters of Wipro, India’s third-biggest software services company, saw his wealth rise by 26 percent to $19 billion in roughly the 12 months since last year’s ranking.This near-term turnaround in fortunes has been triggered by a broader rally in top Indian IT stocks this year as well as a strong growth in the American economy, the largest market for Indian IT. The latest report released by the US’s Institute of Supply Management shows that manufacturing activity in the US has surged to a 13-year high in September.

The IT behemoth that failed to latch on to the tailwinds was Infosys, which saw an 11 percent drop in its stock price after the conflict between founder NR Narayana Murthy and Vishal Sikka, the company’s first professional CEO. In absolute terms, Murthy’s wealth fell only by a small amount—as little as $50 million, in comparison with his estimated total of $1.82 billion after the fall—but his rank tumbled 22 places to 84. Co-founder Nandan Nilekani, who is now back in the Infosys saddle as non-executive chairman, saw his rank dip by nine places to 89. This despite his wealth rising by $90 million to an estimated $1.71 billion over last year’s numbers. Third co-founder Senapathy (Kris) Gopalakrishnan maintained as much wealth as he did last year, but dropped 11 places in the rankings, from 81 to 92.

undefinedIt’s almost a Darwinian scenario, as you will either be a disruptor or be the disrupted.[/bq]

Infosys stocks tanked close to 10 percent on August 18 itself, the day Sikka announced his resignation, and hadn’t recovered much by the end of the September quarter. Nilekani’s return brought about a semblance of stability, but only just. In comparison, Tata Consultancy Services gained over 3 percent in the first nine months this year, Wipro a solid 17.8 percent and HCL Technologies 5.6 percent. Only US-based rival Cognizant Technology Solutions, which has most of its employees in India, did better than Wipro, adding 29.5 percent in the same period.

As the outsourcing industry struggles, India’s top IT companies are trying to build new products that deliver data analytics and predictive data analytics-based information around which they can offer higher-value services. This is part of a larger shift towards providing digital solutions, the demand for which is quickly shifting from small, pilot projects to large-scale implementations that clients expect will increase revenue and boost profitability.

“It’s almost a Darwinian scenario, as you will either be a disruptor or be the disrupted,” says Frances Karamouzis, vice president and distinguished analyst at IT research and consultancy company Gartner. “These were once the darlings, everybody loved them [in India] because they created jobs, but now, here they are in a very different place.”

The linear structure where net new headcount correlated with net new growth is being dismantled, and “hence you see development of Ignio, Holmes, and what was once called Mana and now Nia [the artificial intelligence platforms for TCS, Wipro and Infosys, respectively]”, Karamouzis says.

An important way these companies are adding new capabilities is by buying them. HCL, for instance, has most recently purchased Britain’s ETL Factory Ltd, which sells a data management automation platform called Datawave. Indeed, over the last several years, HCL has emerged as a strong player in infrastructure management services, which has helped it win large contracts.

Wipro’s Premji has invested both in acquisitions to build Wipro’s capabilities, and via his family-office private equity firm Premji Invest, which most recently invested $50 million in Apttus, a California-based software startup. Apttus, which counts salesforce.com as an investor, is said to be close to an IPO, which could make Premji even wealthier.

Acquisitions such as the $500-million purchase of cloud solutions provider Appirio and reputable Denmark-based design firm Designit, a little over two years ago, have put Wipro on a strong footing in the digital era, writes Phil Fersht of IT research and advisory company HFS Research in a September 2017 report. “We view Wipro as a well-resourced, disciplined outfit that could emerge as a genuine contender in the digital race,” he writes.

However, says Karamouzis, the time for incremental change is over and even plans like Infosys’s to hire 10,000 people across four innovation centres in the US just aren’t bold enough. “In their DNA, they are engineers, so they are not afraid of technology or what it can do, therefore in that sense, that part of their foundation is strong,” she says. On the other hand, with more than 80 percent of their workforce being in India, and even many of those permanently based in the US being Indians with a green card, they have a homogeneity, which works against them, she adds. “Eventually if they really want to be global, they need to create more heterogeneity.”

First Published: Dec 07, 2017, 06:13

Subscribe Now