At the middle-income point, rapidly growing countries must undertake structural, economic and policy changes to effectively transition from a low-income, low-wage to a high-income, high-innovation state—thereby successfully avoiding the loss of economic momentum or stagnation. World Bank economists Indermit Gill and Homi Kharas (2016), the first proponents of the term middle-income trap, argue that such economies “must focus on the transition from productivity growth stemming from inter-sectoral resource reallocations to intra-sectoral catch-up technological growth (moving up the value chain). And they must manage a transition to more mature institutions.” At this point, policies that support the growth of ideas and innovation are critical to enable a successful transition from a resource-intensive economy to a high income, knowledge-based economy.

The middle-income trap has plagued countries like Brazil, which have been stagnant at the upper-middle-income level for nearly two decades. On the other hand, blueprints of high-income economies that successfully avoided the middle-income trap, like South Korea, often reveal that common catalysts pave the way for a successful transition into the high-income level. These catalysts include innovation-led growth and institutions that support open trade and technology diffusion.

What kind of innovation—and enabling ecosystem—does India need today to bypass the middle-income trap and compete in the Fourth Industrial Revolution? Is there a policy framework to drive innovation and disseminate its benefits?

The IP Index presents an objective, data-driven analysis of the drivers of global innovation and competitiveness by capturing the IP climate in 50 world economies, covering over 90% of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The report ranks economies based on 45 unique indicators that benchmark activities, critical to building an innovation-led economy—including policy, law, regulation and enforcement. This helps identify how a given economy’s IP system could provide a reliable basis for investment in its innovation and creativity lifecycle.

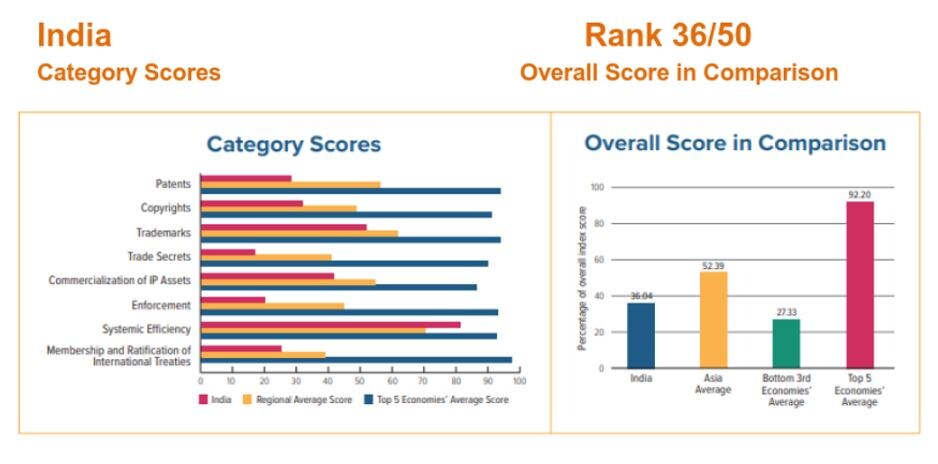

On the 2018 U.S. Chamber International IP Index, India emerged as the most improved country, for the first time breaking free of the bottom 10% of the 50 economies measured. Since then, India has climbed eight places from 44th in 2018 to 36th on the 2019 IP Index—re-emerging as the country that made the largest gain for the second year in a row. What were the enablers of India’s upward trajectory?

The dramatic improvement reflects important reforms implemented by Indian policymakers toward building and sustaining an innovation ecosystem for domestic entrepreneurs and foreign investors alike, closely following the guidelines of its 2016 National Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) Policy. The increase is a direct result of several reforms on existing and new Index indicators: India’s accession to the World IP Organisation (WIPO) Internet Treaties extends the provisions of copyright protection to the digital environment, empowering artists and rights owners with economic rights to negotiate with digital platforms and distributors. India also introduced expedited patent examination processes with specific international patent offices and a dedicated set of IP incentives for small business and female inventors. The government also introduced administrative reforms to address the patent backlog, all of which enhance India’s competitiveness in research and development (R&D)-intensive industries.

Figure 1: India on the 2019 International IP Index![g_122313_ip_index_280x210.jpg g_122313_ip_index_280x210.jpg]() Note: Chart compares India’s scores by category as well as by region, across bottom third and top five economies on the IP Index.

Note: Chart compares India’s scores by category as well as by region, across bottom third and top five economies on the IP Index.

Source: Pugatch and Torstensson, U.S. Chamber International IP Index, 2019. 5

The findings from the 2019 IP Index further highlight the positive spill-overs from broader economic reforms that are captured by other global indices. India was ranked as the “top global improver for a second consecutive year” on the 2018 World Bank Doing Business Report. It registered “the largest gain of any country in the G20” on the latest edition of the WEF Global Competitiveness Report. It also “outperformed on innovation relative to its GDP per capita for eight years in a row” on the 2018 WIPO Global Innovation Index.

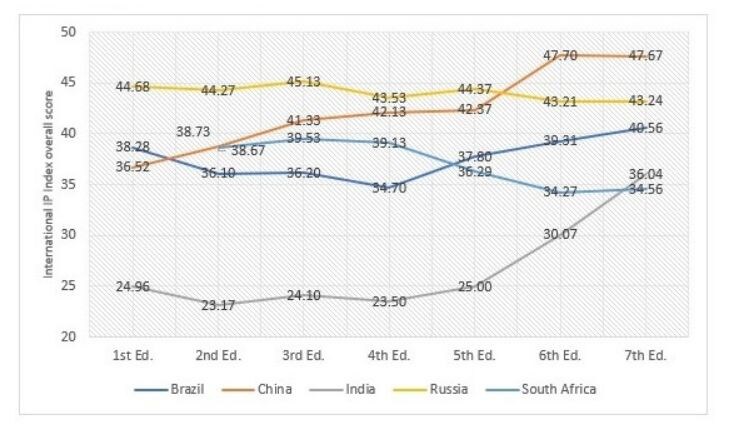

Further dissecting the data from the IP Index, we find three other interesting takeaways: One, in the all middle-income BRICS grouping, India is the only country that has registered a dynamic change in both its score and rank. Its overall score grew by 20% compared to changes ranging from 0.07% to 3.18% among the rest of the BRICS countries. It is also interesting to note that both Brazil and South Africa are upper-middle income countries that continue to remain stuck in the middle-income trap. As the chart below shows, this is an opportunity for India to play catch up.

Figure 2: BRICS Performance Over Time ![g_122315_brics_280x210.jpg g_122315_brics_280x210.jpg]() Note: Overall total score as a percentage of available scores, plotted from the first to the seventh edition of the IP Index

Note: Overall total score as a percentage of available scores, plotted from the first to the seventh edition of the IP Index

Source: Pugatch and Torstensson, U.S. Chamber International IP Index, 2019.5

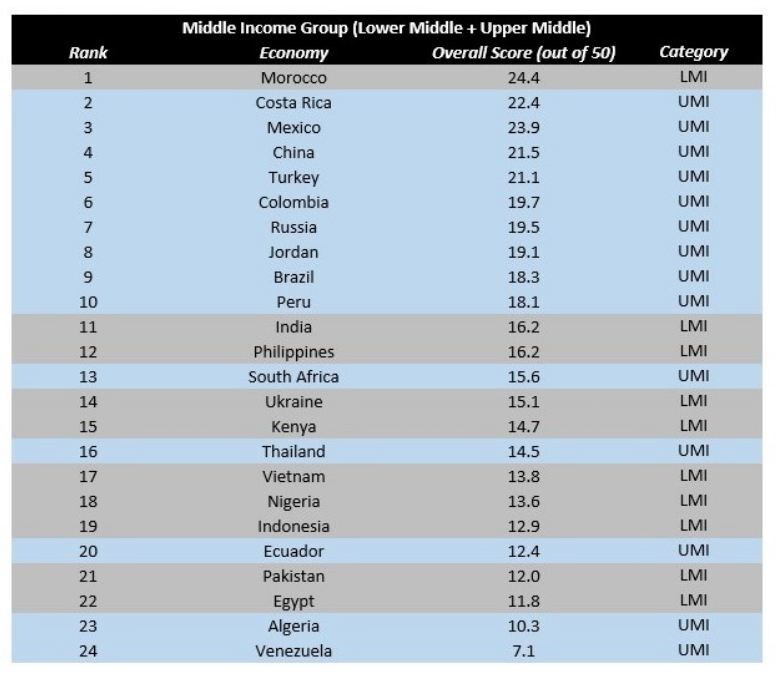

Two, India ranks 11th out of the 24 middle-income economies measured on the Index. If we further split this group into two subgroups using World Bank criteria—lower middle-income (LMI) and upper-middle income (UMI)—India ranks 2nd in the LMI group, behind Morocco (owing to higher IP standards etched in the Free Trade Agreement with the U.S.) and ahead of Philippines, Ukraine, Kenya, Vietnam, Nigeria, Indonesia, Pakistan, and Egypt. In fact, India is already competing with the UMI economies on the Index by outpacing South Africa, Thailand, Ecuador, Algeria and Venezuela, when it comes to adopting pro-innovation policies and laying the ground for a smooth transition out of the middle-income trap, other things being equal.

Figure 3: Middle-Income Economies on the IP Index

![g_122317_middle_income_280x210.jpg g_122317_middle_income_280x210.jpg]() Note: Denoting upper and lower middle-income economies’ scores on the IP Index per World Bank income criteria.

Note: Denoting upper and lower middle-income economies’ scores on the IP Index per World Bank income criteria.

Source: Pugatch and Torstensson, U.S. Chamber International IP Index, 2019. 5

Three, India (rank 36 out of 50) is closely following the heels of transitioning economies like the United Arab Emirates (rank 32), Peru (33rd), Brunei (34th) and Saudi Arabia (35th), who are recognising the importance of transitioning from their resource-intensive economic frameworks to innovation-driven policies.

Challenges in India’s IP System

The above data and analysis from the 2019 U.S. Chamber International IP Index show that as India undertakes steps to improve its innovation ecosystem, it can empower the next generation of Indian innovators, hurdle the middle-income trap, and transform itself into a true knowledge-based economy. While India’s performance on the 2019 IP Index is a welcome progress, as the world’s fastest-growing major economy, India continues to punch below its weight. It is also much easier to go up the ranks when an economy starts with a lower base. In addition, IP-related progress in India is still uneven: India’s movement on copyright and systemic efficiency-related indicators is much more dynamic compared to its stagnant progress on patent-related indicators.

Indian policymakers will need to further streamline the country’s overall IP framework to better support risk-taking and long-term R&D investment in order to develop cutting-edge innovation. This includes eliminating convoluted and superfluous patent laws that adversely affect the timely introduction of innovative products into the market. This includes the arbitrary application of Section 3(D) of the Patents Act as well as a lack of a patent notification system to streamline the innovative-generic transition. Patent applicants are also subject to lengthy pre-grant opposition procedures. India offers no regulatory data protection. If a patent is granted, enforcement of its full term of 20 years remains a challenge.6 Aligning the patentability criteria with global best practice guidelines would encourage innovators to both manufacture and sell in India.

Instead of myopic price control policies, policymakers can ensure access to innovation by encouraging competition in innovation and R&D that could help drive down prices of innovative products. On the enforcement side, piracy is rampant as it remains difficult to pre-determine damages for copyright infringement, and the lack of transparency with regard to seizure of counterfeit goods is a source of frustration for IP-intensive businesses. India is also yet to formalise legislation on trade secrets protection, an important piece of a complete IPR framework.

If India can surmount the serious challenges that remain, it can build a robust innovation-led growth model for other countries to emulate. As a lower middle-income economy, India is already making sustained progress.

As India further develops its IP-driven innovation infrastructure, three areas will be key:

One, Indian policymakers can strengthen the country’s innovation ecosystem by investing more in R&D capabilities, improving the education system, and developing human capital. Amit Kapoor, President and CEO of the India chapter of the Institute for Competitiveness, delves deeper into the strengths and weaknesses of the Indian IP ecosystem, including at the state level. He argues that in a globalised world where knowledge-intensive industries form the bedrock of successful economies, IPRs become the fundamental market institution.

While the protection of IPR is a vital aspect of innovation, a strong patent regime is not an end in itself if the nation does not have the capabilities to harness it, Kapoor shows. In order to aggregate the various factors that define a conducive environment for innovation at the regional level, Kapoor and his team at the Institute for Competitiveness analysed innovation at the sub-national level. While patent filings are concentrated in southern and western India, the states of Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Delhi, Telangana, and Karnataka emerge as most the innovative as far as an exceptional pool of human capital is concerned.

Two, national policies and strategies will need to address the gap between commercial science and market demand to accelerate innovative outputs and subsequently enable the commercialisation of those outputs. Swapna Sundar of IP Dome has argued that the large proportion of technology input that goes into India’s digital environment and experience is developed, owned, managed, maintained and delivered by foreign companies. While India is not new to innovation, Indian innovators are yet to address the gap that remains between industry and academic research.

Through IP Dome, Sundar and her team provide mid-market companies with cost-effective and powerful solutions for IP-led growth founded on sound research and analysis. Policymakers could focus on encouraging the setup of design centres in India and consider a value-added method of measuring economic growth to identify areas and sectors that can strengthen innovation-driven competitiveness. Encouraging technical education in schools and colleges is a step in the right direction, but more needs to be done to overturn the disconnect between academia and industry. Investment in R&D and skills, and policies to reallocate resources to innovative sectors, can offer an attractive path forward for Indian innovators to rise up, commercialise their inventions, contribute to the growing demand in the domestic market itself. In this direction, India can eventually supplement IP-led innovation in other economies.

Three, reshaping the IPR regime with the understanding that activities that contribute to innovation are more likely to occur where innovators can ensure a fair return on their investments, thereby incentivising technology transfer. Professor Mark Schultz, who studies and teaches IP at the University of Southern Illinois, further deconstructs the importance of a key 21st century IP tool to boost competitiveness – trade secrets protection. A “trade secret” is information that is used in business (“trade”) that is not known to the public or others in the industry (“secret”). Protecting trade secrets is important as essentially every patent (the quid pro quo for which is public dissemination of new learning) begins life as a trade secret – the IP system contributes greatly to this security, he argues.

Professor Schultz explains why trade secrets may be the most important form of IP for business. In one of his most influential projects, he worked with the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) to construct a global Trade Secret Protection Index (TSPI) measuring 40 major economies by analysing about three-dozen objective components of trade secret protection in their national legal systems predicated on the basis of strong and statistically significant positive relationship between the effectiveness of a country’s trade secret law and key indicators of innovation. India falls into the lower scoring group with a score of 2.92. Nonetheless, with its sound legal system, India is well-positioned to modernise its trade secrets law in order to address misappropriation by third parties through corporate espionage, by providing for both criminal enforcement and given the fragile nature of trade secrets, swift injunctive relief. In his own words, “Metaphorically speaking, patents and trademarks may be the peaks of the innovation system, but trade secrets are the mountain ranges from which those peaks rise. Without the range, there are no peaks.”

The 2019 IP Index find that economies with strong IP frameworks are 40% more likely to adapt to the Fourth Industrial Revolution8 and secure new growth opportunities—an indispensable pole to vault over the impending middle-income trap. India’s growing investment in IP and foundational policies—including consistent consultations with stakeholders on new IP policies and the launch of educational and awareness programmes across the country—are all steps in the right direction.

This piece originally appeared in ISB Discover from the Indian School of Business. To receive business ideas and insights from ISB Discover, click here:

ISB Discover

Image: Shutterstock[br]As the world’s fastest-growing major economy, India will soon move closer to its next milestone—the

Image: Shutterstock[br]As the world’s fastest-growing major economy, India will soon move closer to its next milestone—the  Note: Chart compares India’s scores by category as well as by region, across bottom third and top five economies on the IP Index.

Note: Chart compares India’s scores by category as well as by region, across bottom third and top five economies on the IP Index. Note: Overall total score as a percentage of available scores, plotted from the first to the seventh edition of the IP Index

Note: Overall total score as a percentage of available scores, plotted from the first to the seventh edition of the IP Index Note: Denoting upper and lower middle-income economies’ scores on the IP Index per World Bank income criteria.

Note: Denoting upper and lower middle-income economies’ scores on the IP Index per World Bank income criteria.