Sanjiv Mehta: Creating a faster, nimbler HUL

By decentralising decision-making, he has made it easier for Hindustan Unilever to operate with the speed and swiftness of his smaller rivals

Sanjiv Mehta, Chairman & MD, HUL

Sanjiv Mehta, Chairman & MD, HUL

Forbes India Leadership Award 2018: Best CEO-MNC

In 2015, Srirup Mitra, 36, the then category head of Hindustan Unilever Ltd’s (HUL) hair business, was in for a surprise. He was summoned to the management committee, the top decision-making body that runs the company, and told as he recalls, “From this day onwards, ask for forgiveness before asking for permission.” In effect Mitra was being told to take bold decisions and then run with them. A new structure was unveiled and Mitra found himself as head of HUL’s hair care business with complete autonomy over day-to-day operations.On Sanjiv Mehta’s part it was hardly an empty promise. The chairman and managing director of HUL was pushing through the biggest decentralisation of decision-making the company had seen. A year later when Mitra went to the board to plug the ayurvedic gap in his portfolio, all he needed were four meetings with the management committee to buy out Indulekha—HUL’s first big acquisition after Lakme two decades ago. The only points of discussion were the valuation and the final clearance to do the deal. In the past, a similar process would have filtered across many more layers and played spoilsport with speed—a key ingredient in HUL’s decision-making process today.

Mehta’s faster and nimbler HUL has played a crucial role in taking on rivals. “Being larger does not give us a licence to win,” he says, pointing out how the company needs to experiment a lot more. And the Indulekha acquisition is a good indication of the change he’s brought about. Two years ago at HUL’s quarterly results press conferences, Mehta would get asked as many as a dozen questions on the Patanjali threat. (Today Patanjali rarely features in the questions.) In his trademark style he’d say that he’s focussed on running his business and that he respects all rivals. He now proudly points out that in the last five years HUL has added more in sales than the entire size of Patanjali (₹10,560 crore). He’s achieved this in no small measure through a “massive rewiring of the company while the mains were on” that has made HUL fit to take on everyone from regional brands to Procter & Gamble and Henkel.

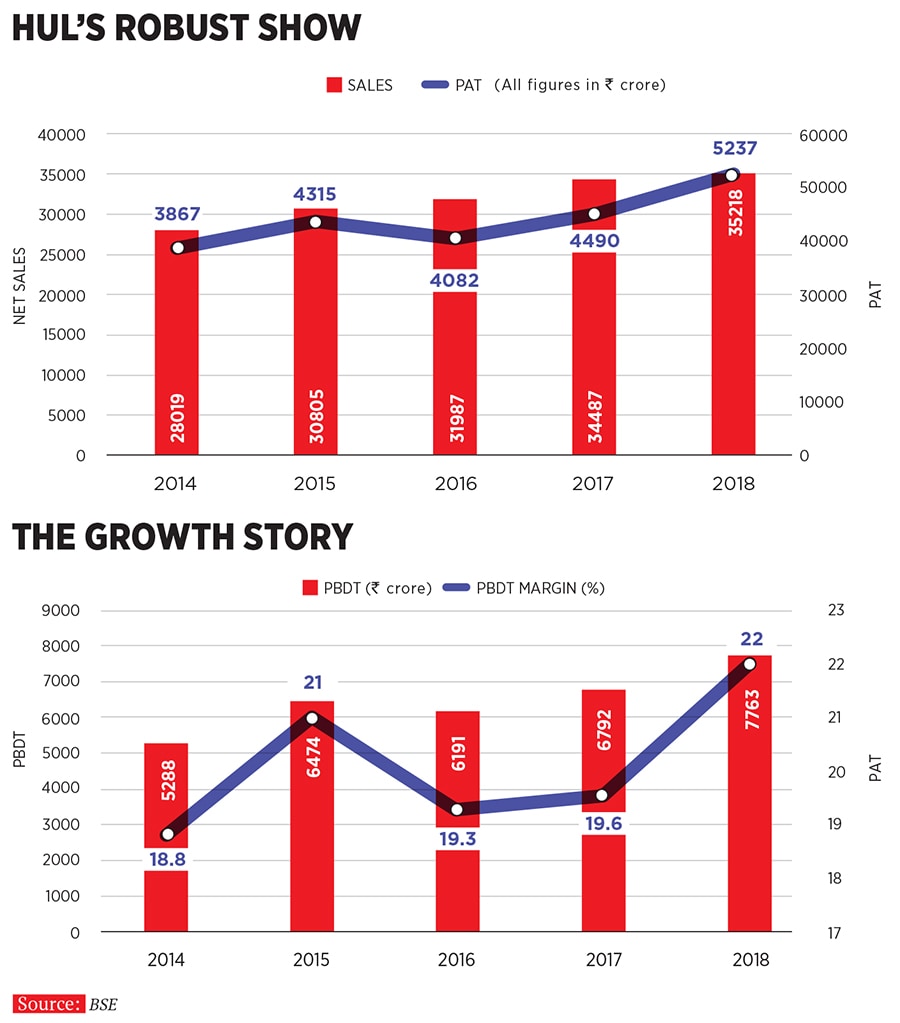

Mehta has steered the company through demonetisation and the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax. At the same time rural demand cratered on account of the monsoon failing in 2014 and 2015. The reduction in oil prices and benign food inflation were tailwinds. So while sales rose by 5.5 percent a year to ₹35,218 crore in the year ended March 2018 and profits rose by 6.8 percent to ₹5,237 crore in the same period, volume growth was a robust 8 percent and margins expanded from 14.2 percent to 18.1 percent. To get a sense of how vast HUL has become one needs to consider that its profits are now more than the sales of rivals Marico, Dabur and Godrej Consumer Products. Keeping a vast and unwieldy organisation primed for growth has been Mehta’s key achievement.

Putting it in place

In October 2013, even before Mehta arrived at HUL’s corporate office in Chakala in suburban Mumbai from Dubai (as chairman of Unilever North Africa and Middle East), he’d already sent out a note asking the management committee for histories of brands and their strengths and weaknesses. His predecessor Nitin Paranjpe who now heads Unilever’s food and refreshment business had brought the company back on the growth path after almost a decade of stagnating sales. The most important development had been the trebling of rural direct distribution reach, which allowed HUL to reap rich rewards with increased rural spending on consumer products. In the initial years, a large part of the approximately ₹60,000 crore transferred to rural India through the Employment Guarantee Scheme made its way to purchases of sachet-sized soaps, toothpastes and detergents. The new consuming class had emerged. Clearly Mehta had a tough act to follow in keeping this juggernaut rolling.

Mehta, who’d done stints for the company in Bangladesh, the Philippines and then in Dubai, had never worked in India. He also spent his first 100 days travelling the length and breadth of the country visiting customers, dealers and talking to analysts and the competition to form his own impression of the company. He did this to allow him to lead discussions and steer the management committee to a particular line of thinking. In what Mehta describes as typical HUL style, he received from the committee an 8,000 slide presentation filled with a SWOT analysis of their brands.

What stood out was that even though the company operated in much the same manner in which it has been for the last two decades with five zones, the Indian market was far more heterogeneous than that. This was something he had seen in his Dubai stint when he was responsible for operations in 20 countries. Brands that were strong in one geography required more marketing spends in others. Even within a state there were seasonal variations in demand. And customers responded differently to the same promotions run in two different parts of the country. Parts like central India (Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh) had low levels of penetration.

Importantly, HUL at ₹28,019 crore in sales in 2014, had also reached the size and scale where it could justify the costs involved in segmenting the country more effectively. Initially the southern states were split into four zones and when it became clear that this was the way to go, the ‘Winning in Many India’s’ strategy was unveiled with 14 new zones carved out.

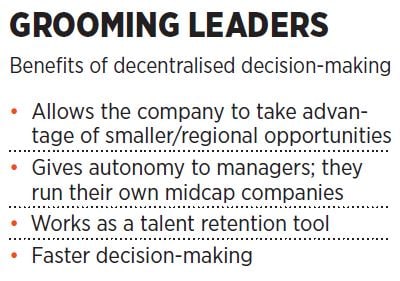

At the same time, Mehta also segmented business units—country category business teams—in line with what Unilever has done globally. These 15 jobs would make managers responsible to a category—tea, hair, soaps, detergents and so on—and they’d have their own (informal) board, own sales and marketing teams, own supply chain, access to R&D and human resource facilities and the freedom to make their own budget. “All decision-making has moved down one level and we think of ourselves as the HUL tea company,” says Shiva Krishnamurthy, vice president, tea and foods, at HUL. The only time he needs to keep his bosses informed is for category launches and for 8-12 quarter guidance on how the business is expected to perform.

This decentralisation has allowed Krishnamurthy to experiment with different pack sizes and increase the varieties of tea sold across states. He says the feedback from the ground up is a lot faster and helps them take on regional brands more effectively. Mitra, his colleague who runs the hair care business, says, “Earlier we would only focus on much larger, say ₹3,000 crore opportunities. But now even if it is a ₹100-200 crore opportunity, we’d be willing to try it out in a few clusters.”

Mehta calls the category

business teams and the cluster head jobs as “among the most powerful in the company today”. It’s the dovetailing of the two roles that has allowed the company to function like a midcap FMCG company. So while the team running soaps would decide what variant to launch in water-starved Karnataka, it is the cluster head who’d take a call on how media spends are to be deployed in that area or what promotions are to be activated when.

Take the case of Fair and Lovely, one of HUL’s best known brands. In the 1990s, the main challenge was to get people to move from sachets to tubes and so a regional strategy worked. But now some clusters have 90 percent penetration while others have only 30 percent so deploying resources and deciding what pack sizes to launch has to be done differently. Earlier this year when Ponds Starlight talc was launched, there was a view that this product wouldn’t work in Uttar Pradesh. But when the cluster pitched for the product to be launched, they managed to convince the category team, even though it was a big decision, as they needed to move to Hindi media.

The new structure has also given HUL an opportunity to retain talent as category managers are running midcap companies in their own right. Mehta sees these jobs as preparing grounds for future Unilever talent. “The trick with these new roles is that you are no longer just a marketing head but also a business head. So you need to balance the competing demands of marketing, supply chain, business financials and so on,” says Prabha Narasimhan, vice president, skincare, at HUL.  Data, the Equaliser

Data, the Equaliser

With his teams in place, Mehta’s time is spent mostly on working out how the HUL of the future will function. A key change over the last decade has been the use of data. Mehta believes this is a real advantage for Unilever’s Indian subsidiary as in the earlier industrial era, developing countries had few advantages other than frugal innovation but now data can be a great equaliser.

Two platforms, LiveWire and Jarvis—the latter was made in India —have resulted in all company data being at his fingertips. He gets real time secondary sales data and primary sales data with just a day’s lag. Is a price cut working? The company can answer the question the next morning. What was the average cost of packaging (a derivative of crude oil prices) for the last six months? That too is available real time.

Now HUL is working on building artificial intelligence into these platforms. With Bayesian statistics, the platforms should be able to predict actions with lesser human interference. It would allow the company to decide where to deploy media spends at what time of the year or where customers are moving beyond sachets, say six months in advance. HUL hopes to take these systems global.

Then there are other running experiments. Humara Shop is a website that HUL is using as a learning ground to understand online retail. At present the service delivers to customers in Mumbai, Delhi and Gurugram. Mehta says it would be premature to discuss their learnings in any detail. Or the use of cobots at their warehouse in Meerut, which allows the company to run their warehouses without any human intervention.

For now the numbers have begun to stack up. At his latest quarterly results presentation in October, Mehta had a spring in his step when he announced that the company had grown volumes at 10 percent ahead of the 7 percent industry growth rate. Profit was up by 12 percent to ₹1,525 crore. In contrast, his smaller rivals Emami, Dabur and Godrej Consumer all reported lackluster numbers. HUL is now the largest Unilever subsidiary in volume terms and second largest in value terms. After five years at the top, Mehta’s would be large shoes to fill. Fortunately, he will leave a healthy business where his successor can hit the ground running.

First Published: Nov 22, 2018, 16:47

Subscribe Now