If she was a painter, it would reflect in her paintings. If she was a writer, it would show in her writing, she says. “Maybe to a certain extent as a director, it comes out in my direction."

The actor-filmmaker is currently “overwhelmed" by the appreciation coming her way for her short film The Mirror, which is part of Netflix’s Lust Stories 2 anthology. A review by Raja Sen for Mint Lounge, for instance, called it “one of the finest Hindi films in years".

The story is about an affluent woman who returns home early from work one day to find her domestic help having sex on her bed without her consent. She soon understands that she derives pleasure from watching her domestic help, while the latter enjoys being watched. The narrative explores how both women make sense of their desires, while drawing intersections with class hierarchies, social conditioning and ideas of morality.

Glimpses of Sensharma’s social sensitivity were also visible in her 2017 directorial debut A Death in the Gunj, a script she wrote based on a story by her father, writer-journalist Mukul Sharma, and personal childhood experiences of visiting McCluskieganj in Jharkhand. The film—through dynamics of an extended family vacationing in the hilly town in the days leading up to New Year 1979—reflects on the tragic consequences of toxic masculinity, alienation and lack of empathy.

The story is also about how people can usurp spaces that do not belong to them, simply through economic might, Sensharma points out. She describes the characters of Maniya and Manjari, the local Adivasi couple who serve as domestic helps for the family in McCluskieganj. There’s a scene where a few members of a family struggle to shoo away a frog that has entered the bathroom. They scream, but none of them approach the amphibian, until Manjari casually moves it away with her broom.

“It’s not a scene anyone would notice, but it was important for me. It was to show that the space belongs to Manjari and Maniya, it’s their natural setting, and the family members were simply not at home in the world there," Sensharma says, before adding, “Maybe, subliminally, that scene is making a difference somewhere, I don’t know. But these are truths that we live with."

As film critic Anupama Chopra puts it, it’s not cinema’s job to provide answers, but Sensharma’s films always ask the right questions. That’s also got to do with her lineage and upbringing, she points out. Konkona—or Koko, as she is referred to by friends, family and colleagues—comes from a storied family. Her mother is reputable actor-director Aparna Sen, and her grandfather is filmmaker Chidananda Dasgupta, who founded the Calcutta Film Society along with Satyajit Ray, among others, a few months after Independence in 1947. “She comes from a family of intellectuals and thinkers. These are people who have led a thoughtful life, who think through things. You can see that in Konkona’s films as well," says Chopra, who is the founder-editor of Film Companion.

Sensharma admits that a life of privilege often insulates you from social realities, and that she is also not aware of a lot of things, except for, say, gender followed by caste and class-related issues. “Even then, it’s not like I’ve understood those dynamics completely. But I’ve become much more aware. One has to educate oneself also," she says.

![]() (From right) Konkona Sensharma on the sets of The Mirror, a short film she directed for Netflix"s Lust Stories 2, with actors Amruta Subhash and Tillotama ShomeImage: Netflix

(From right) Konkona Sensharma on the sets of The Mirror, a short film she directed for Netflix"s Lust Stories 2, with actors Amruta Subhash and Tillotama ShomeImage: Netflix

‘Did not care about outcomes’

In a recent interview, Sensharma said that she is not a career director, and considers herself an actor first. But admitting to herself that she is an actor by profession, and developing an appreciation for the craft, came after a lot of denial.

She practically grew up on film sets and she was comfortable being there. As a kid, she often accompanied her mother to her workplace. “I went with her everywhere, whether it’s for shooting, editing, dubbing, mixing, or even pre-production or budget meetings. I was very familiar with the world and that was a huge help," she says.

She was five-odd years old when she acted in a Bengali film called Indira. As a teen, she acted in her grandfather’s film Amodini, and followed it up with Ek Je Aachhe Kanya in the early 2000s, her first Bengali film as an adult. That was a time she was pursuing a degree in English literature from St Stephen’s College in Delhi.

She says she was so focussed on doing her Masters that she did not think about acting per se, although as she figured out what she wanted to do in life, it was easy for her to go down that path. “I was a bit of a dreamer, bit of a slacker, by and large doing the bare minimum to exist in my own world," she says.

Filmmaker Jaydeep Sarkar, who has been friends with Sensharma since her days at St Stephen’s, says she had shown glimpses of her exceptional acting talent early on. She had essayed the role of Goddess Kali in a stage adaption of Girish Karnad’s Hayavadana. “It was a brief role, but I remember all reviews spoke about what a phenomenal performance it was. It left such an impression on people," says Sarkar, who, many years later, would cast Sensharma as the protagonist in his short film Nayantara’s Necklace.

Sensharma says she soon grew bored of her Masters degree course (“They were teaching the same thing—Milton, Chaucer—I had already done all that"). It was during this time that her mother offered her the titular role in her directorial Mr and Mrs Iyer, for which Sensharma would earn her first National Award. “I remember even after Mr and Mrs Iyer, I used to scan classifieds in the newspapers looking for jobs," she says.

The actor was still living in Kolkata and had also done a film, Titli, with late director Rituparno Ghosh, when her first Hindi film, Madhur Bhandarkar’s Page 3, came her way. After that, projects kept coming her way one after another, and she eventually relocated to Mumbai. “After every film I thought ‘Nahin, iske baad main job dhoond loongi [no, I’ll find a job after this], and it took me a while to accept that I was acting. That I was able to do interesting things, earn money, live on my own. So I just accepted it," she says, and after a small pause, adds. “The appreciation for my craft came much later."

Given that she did not take the prospect of being a career actor seriously helped her detach herself from the outcome of her films, which, according to her, was very liberating. “I didn’t care how the film did. I cared that I did my work properly, had good relations with people, and was sincere and hardworking, but aisa nahin tha [it wasn’t such] that I had to make it with Page 3," she says.

When Sensharma was working on Page 3, Sarkar was assisting Sudhir Mishra on the Hindi film Chameli, and along with a bunch of college friends who were also in Mumbai, they would often hang out after work. He found her to be an actor who worked hard to get things right. “I remember, for someone whose native language is not Hindi, she put in a lot of effort to deliver her lines right," he says.

Sensharma’s initial films, possibly unbeknownst to her, have been an inspiration to others. Actor Amruta Subhash, who played the role of Seema, the domestic help, in The Mirror, says that Sensharma was part of her psyche long before she met her, from the time she first watched her in Mrs and Mrs Iyer. “I was very young at the time and felt like I had found someone I could relate to on screen. Koko was unconventional, unique and beautiful in her own way. I was relieved to watch her and felt like that uniqueness had a place in the film industry," Subhash says.

Later, when Sensharma signed on mainstream commercial Hindi films like Ayan Mukerji’s Wake Up Sid with Ranbir Kapoor and Zoya Akhtar’s Luck By Chance alongside Farhan Akhtar, Subhash says it gave her more confidence in her own career path. “I felt like you just have to be yourself and not make an effort to fit into a certain box. Koko’s journey shows me that there is space for everyone in this industry, a good space, not a compromised one."

Sensharma credits her mother as one of her biggest inspirations, and says that she has particularly imbibed her meticulous work ethic. Chopra of Film Companion says that even though one gets glimpses of similar sensibilities that the two might have, Sensharma is “unique" as an actor and director. “Her mother, as an actor, did full-on commercial films, while as a filmmaker, she took a different direction. But Konkona’s choices, be it as an actor, writer or director, have always been left of mainstream," she says.

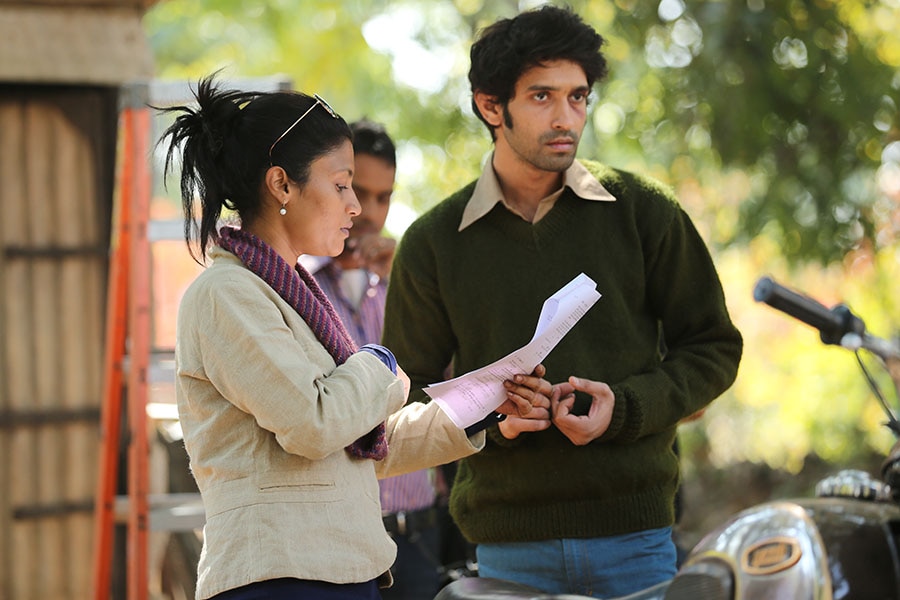

![]() (From left) Konkona Sensharma on the set of her directorial debut "A Death in the Gunj" along with actor Vikrant Massey.

(From left) Konkona Sensharma on the set of her directorial debut "A Death in the Gunj" along with actor Vikrant Massey.

‘She’s got your back’

Be it then or now, Sensharma says she has never planned anything in her life. But as an actor or director, once she has decided to do a project, she preps “to death", and finds it self-soothing to go over a plan. How much she preps depends on how removed her own life is from the realities of her character—economically, religiously, or in terms of sexuality. “Different directors expect different things, so I adjust and adapt based on what they want," she says.

Her colleagues in the industry attest to the diligent student-like approach she brings to a role, in order to embody the characters she plays with sensitivity and empathy.

Neeraj Ghaywan, director of the short film Geeli Pucchi in Netflix’s 2021 anthology Ajeeb Daastaans, where Sensharma played the character of a queer Dalit woman, remembers how he had told her not to approach the subject of the film with an outsider’s gaze, and she made every effort to ensure it is not so. He says there was the question of why he did not cast someone from the Dalit community for the role, but did not know anyone who could do justice to the role like Sensharma. “She has the intelligence to understand the nuances of such a complex script, and comes from a place of empathy and understanding," he says.

The filmmaker shares how Sensharma used to come to rehearsals and workshops dressed in jeans, shirt and a jacket—just like her character in the film—and even found hair and makeup artists from the community to make sure she looks the part and is able to do justice to the role. Ghaywan calls her a proactive actor who internalises her character.

He remembers how he wanted her to cry in one scene, and she, on-the-spot, cried in three different ways and asked him which would suit her character the most. While shooting the scene, they did eight re-takes, “and in each take, she cried at the same exact point that was expected, and cried in exactly the same way," he says. “Many actors can’t go beyond four-odd takes in crying scenes because it can wear you down emotionally. But Konkona’s process is different. She later told she uses breathing techniques to get into emotional zones." Ghaywan says he was “bowled over" by Sensharma’s work with The Mirror, and that he has “never seen an actor go so far in terms of craft behind the camera".

![]() Konkona Sensharma (left) at a press conference for her film Mr and Mrs Iyer, directed by her mother Aparna Sen (right)Image: Jayanta Shaw / Reuters

Konkona Sensharma (left) at a press conference for her film Mr and Mrs Iyer, directed by her mother Aparna Sen (right)Image: Jayanta Shaw / Reuters

Subhash says that Sensharma understands vulnerability as an actor, and gives actors in her films the space to bloom. Her role in The Mirror required her to do many intimate scenes, and she remembers how her director would boost her confidence before every shot. “She would say, ‘Everything’s fine. You’re fine’. That meant a lot to me," she says, adding that Sensharma knew exactly what she wants from a scene, which meant she was always calm on set. “She was clear what she wanted, but was also open to opinions and suggestions. That’s what makes her a confident director."

Sensharma admits that knowing exactly what she wants could also be a problem, because she is only “one-and-a-half films old" as a director. Whenever she writes a script, she tells the story to a small circle of people who are close to her. She tells them the story again and again to gauge where she is losing them, what they are interested in, how she is able to communicate her ideas, and which parts are not working. “At those times, you are also making stuff up. So it’s a very creative process, the telling of the story," she says. She takes the feedback of this close circle seriously, but “ultimately, it’s me".

Director Alankrita Shrivastava feels the industry has not yet fully explored the depth of Sensharma’s talent. “She is a very supportive actor who, being a filmmaker, understands your stresses and is very calm and chilled out. She’s warm, encouraging and brings a good energy to the set. She makes you feel like she’s got your back," says Shrivastava, who directed Sensharma in Lipstick Under My Burkha (2016) and Dolly Kitty Aur Woh Chamake Sitare (2019). The filmmaker says one of Sensharma’s strengths as an actor is her ability to communicate with her eyes. “Her eyes help her say a lot without her doing much."

Shrivastava also believes that “Koko never lets success define her in a way that she loses touch of reality". Ask Sensharma how she measures success, and she just waves her hand in the air. “Do we have to? I don’t think we need to measure success," says the actor-filmmaker, who is working on developing an idea for a series and a feature film, and who will be seen in Anurag Basu’s film Metro… In Dino, a sequel to his 2007 film Life in a… Metro.

There are a few things that are very important to her in life, she says. She should be able to look after herself and her loved ones, she should have good relationships with people, behave in an ethical manner, and have peace of mind. “Beyond that, I don’t think about success," she says. “Just work hard and be kind."