Pressing the EV accelerator

The government is making a fervent push for electric mobility and the two-wheeler industry is on its toes to meet the growing demand

Image: Nishant Ratnakar[br] There is a massive churn underway in India’s automobile sector and it has nothing to do with the slowdown plaguing the economy. At the forefront of the transformation is a growing interest in the electric two-wheeler segment, which has the potential to shake up the pecking order of India’s two-wheeler industry. Consequently, market leaders, including Hero MotoCorp, Honda Motorcycles and TVS, could lose their market shares to companies that were born in this century.

Image: Nishant Ratnakar[br] There is a massive churn underway in India’s automobile sector and it has nothing to do with the slowdown plaguing the economy. At the forefront of the transformation is a growing interest in the electric two-wheeler segment, which has the potential to shake up the pecking order of India’s two-wheeler industry. Consequently, market leaders, including Hero MotoCorp, Honda Motorcycles and TVS, could lose their market shares to companies that were born in this century.

In August, Mahindra announced plans to foray into the segment while Pune-based Bajaj Auto is also working with strategic partner KTM to look at an electric solution for a high-end motorcycle. “We are watching this space. We have some plans up our sleeve. We will have a locally manufactured two-wheeler,” Anand Mahindra, chairman of Mahindra Group, told shareholders.

India’s largest two-wheeler manufacturer, Hero MotoCorp, has already pumped $51 million (₹350 crore) into Bengaluru-headquartered Ather Energy in two separate rounds of funding as it looks to up its game in the electric two-wheeler segment. Currently, companies such as Hero Electric, BSA, Electrotherm (India) and Lohia have launched electric two-wheelers. So have startups like Okinawa, Ather Energy, Ampere, Twenty Two Motors and Revolt Motors, while Japanese motorbike manufacturers such as Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki have confirmed plans to develop electric vehicles (EVs).

“Conventional companies that were opposed to the idea of EVs have now begun to factor in electric mobility in their short and long term plans,” says Sohinder Gill, CEO of Hero Electric, and director-general of the Society of Manufacturers of Electric Vehicles (SMEV). “Over the past two years, the government has been shouting from the rooftops about electric mobility. That has brought about a change in mindset, although a lot still needs to be done.” Sohinder Gill, CEO of Hero Electric[br]Changing mindset

Sohinder Gill, CEO of Hero Electric[br]Changing mindset

It is perhaps the need of the hour given that Indian cities invariably find a mention on the list of the world’s most polluted cities with New Delhi often topping the names.

“In the last few years, there have been two big changes,” says Tarun Mehta, co-founder and CEO of Ather Energy. “The biggest has been how consumers look at EVs. Ultimately a market is created if there is customer demand… when people like a product and are comfortable with the technology. Customers are no longer walking into showrooms expecting a puny vehicle. They expect to be wowed by the performance. They are now expecting EVs to be an upgrade that is a huge perception change among customers.”

Much of that change in perception is also thanks to global carmakers such as Mercedes, Tesla and BMW who have been instrumental in pushing electric mobility worldwide.

“Also, governments around the world are backing the shift to electric and talking about it,” says Mehta. “Regulations are being formed and implemented. This has, in turn, created plenty of positive news about electrics, the options available and the pros and cons of the technologies in the market today. Therefore, the biggest shift in the last two years has been in customers’ awareness and willingness to buy EVs.”

In India, the government had announced plans to allow the sale of only electric three-wheelers from April 2023 and electric two-wheelers under 150 cc from April 2025 onwards. However, in August, Nitin Gadkari, minister of road transport and highways, said, “There is no deadline as of now. The shift towards EVs will happen in natural progression.”

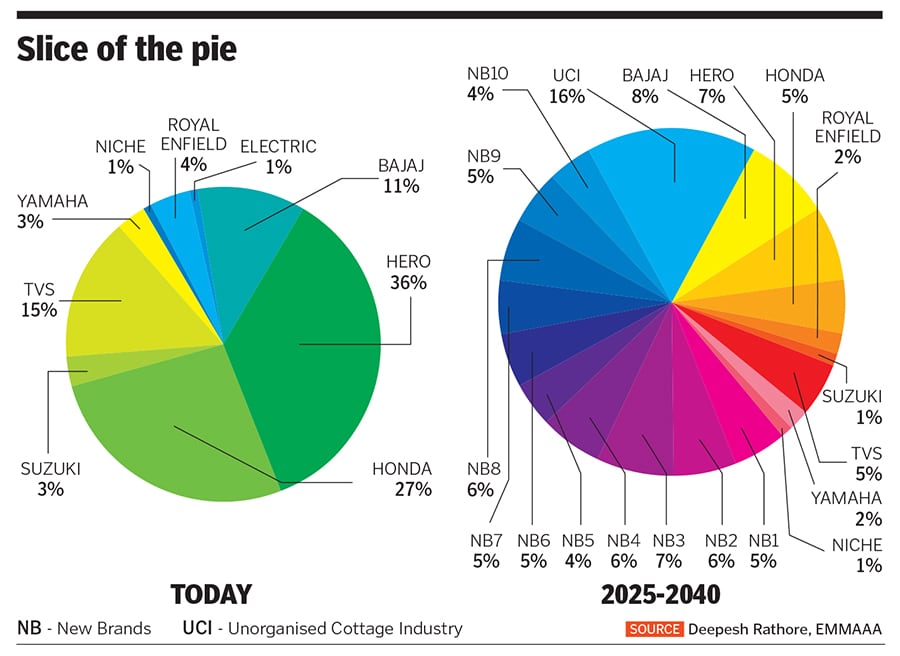

“The 150 cc category has been commoditised,” says Deepesh Rathore, co-founder of Gurugram-based automotive consultancy Emerging Markets Automotive Advisors (EMMAAA). “There isn’t much difference between the products, barring factors such as the brand or the experience. That means there is a huge opportunity for companies to tap into that segment.”

Rathore reckons that by 2030, India will sell nearly 54 million two-wheelers, of which about 43 million (of 150 cc) will be electric two-wheelers. “Until then, established players will be laying the groundwork and only about 10 percent of the bikes sold in India will be electric.” Last year, India sold over 21 million two-wheelers.

Others believe one can expect an inflection point around 2025. “In India, [production and sales of] electric two-wheelers are expected to increase in the years to come,” says Vinay Piparsania, global consulting director, automotive, at of Hong Kong-based Counterpoint Technology Market Research.

In an interview to Forbes India earlier this year, Rahul Sharma, founder of Micromax and Revolt Intellicorp, had said: “People are giving all sorts of timelines for EV transitions. They are miscalculating and misjudging the transition time.” Sharma, who founded Revolt Intellicorp in 2017, recently launched an electric two-wheeler with a range of 156 km on a single charge. It operates through an app, which is available on Android and iOS.

The shift towards electric will also be helped by a price increase in the conventional two-wheeler market, after the implementation of the Bharat Stage (BS)-VI emission norms. The BS-VI is touted to be the most advanced emission standard for automobiles, equivalent to Euro-VI norms. Automobile manufacturers have to reduce nitrogen oxide emissions by 68 percent, and particulate matter emissions by five times compared to existing standards. “Many companies believed that once they shift to BS-VI, they would not have to move towards electric,” says Gill of SMEV. “That has changed.”

Rising cost of fuel could also be a cause of concern. “Two years ago people would have seen electric as a way to save money and not necessarily a better option,” says Ravneet S Pokhela, chief business officer at Ather Energy. “Today they see it as a genuinely better option.”

India has over 40 electric two-wheeler manufacturers, many of whom have been importing components from countries like China and selling them here. “Many are fly-by-night operators who will leave the market soon,” says Rathore of EMMAAA. “Some would be bought over by conventional players.”

“In the past, component supplies were a price barrier to manufacturers,” says Rathore. “For the new entrepreneurs, this has gone as EVs require minimal components. They can be sourced for cheap from countries like China. Even the battery can be replaced.”

Taking Time

Despite the potential it offers, full-fledged adoption of EVs will take a while. India is the world’s biggest market for scooters and motorcycles with annual domestic sales exceeding 19 million in the fiscal ended March 31, 2018. The next biggest market is China, with annual motorcycle sales of about 17 million in 2017. Electric scooters make up a fraction of the total. In 2018, 1.26 lakh electric two-wheelers were sold in India, compared to 54,800 units in 2017, according to SMEV. “EVs have evolved to a stage where mass adoption is possible, but the actual volume is missing for now. That is why purchase prices are still higher, compared with petrol-driven scooters. That’s why government subsidies will play a vital role,” says Mehta.

Electric scooters make up a fraction of the total. In 2018, 1.26 lakh electric two-wheelers were sold in India, compared to 54,800 units in 2017, according to SMEV. “EVs have evolved to a stage where mass adoption is possible, but the actual volume is missing for now. That is why purchase prices are still higher, compared with petrol-driven scooters. That’s why government subsidies will play a vital role,” says Mehta.

There is also the question of how companies will lure customers. “One of the key differentiators as far as electric two-wheelers go is how they set up a showroom and deliver the product because it’s going to be different from existing practices,” says Arvind Singhal, chairman of consultancy firm Technopak Advisors. “The repair and maintenance aspects are also minimal.”

Then there is the government’s Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles in India (FAME-II) scheme where 10 lakh registered electric two-wheelers will be eligible to avail an incentive of ₹20,000 each. It will also support 5 lakh e-rickshaws having ex-factory price of up to ₹5 lakh with an incentive of ₹50,000 each.

Earlier this year, Minister of Finance Nirmala Sitharaman had announced customs duty exemption on lithium-ion cells, a key component of electric two-wheelers, to help lower the cost of lithium-ion batteries in India as they are not produced locally. She also announced income tax rebates of up to ₹1.5 lakh for customers on interest paid on loans to buy EVs, with a total exemption benefit of ₹2.5 lakh over the entire loan period, to push towards electric mobility. In July, the Goods and Services Tax Council decided to reduce tax rates on EVs and chargers from August 1. The rate was reduced from 12 percent to 5 percent on vehicles and from 18 percent to 5 percent on EV chargers.

Despite that, Gill of SMEV feels the government needs to do more. “Some agencies are pushing towards electric mobility while others have been dilly-dallying. The government’s decision to push for greater localisation under the FAME-II scheme is also leading to poor quality,” says Gill.

Eventually, however, it won’t be government subsidies that will decide the future of EVs, says Vishwas Udgirkar, a partner at Deloitte India. “Nobody can, in principle, oppose the idea of electric mobility. The question is whether it will take three years or five years or more.”

“I believe it will be a function of the market. Numerous factors are at play here. Finance, a second-hand market and consumer interest will be the key factors,” he adds.

Meanwhile, India’s richest man, Mukesh Ambani, and the country’s public sector oil companies are betting elsewhere. Reliance Industries (RIL) has already partnered with BP to set up 5,500 retail outlets while state-run public sector companies are now looking to add 78,493 new petrol pumps over the next few years.

“Our analysis shows that EVs will grow rapidly, but oil will continue to have a major share in transportation by 2040,” a RIL spokesperson told Forbes India earlier.

By the looks of it, both seem to be right. “Two-wheelers and three-wheelers make up for a relatively small part of the entire oil demand,” says Rathore. “Technology will take its due course and a lot of change will happen over the next decade and redefine mobility as we know it.”

First Published: Aug 27, 2019, 15:45

Subscribe Now