Mike Walsh: The algorithmic leader

A new breed of leader is emerging with an ability to imagine innovative ways to use machine intelligence to transform organizations—and reinvent the world. Futurist Mike Walsh explains.

Mike Walsh[br]Q. Karen Christensen: You have said that in today’s environment, “every company is an algorithmic company, whether it knows it or not.” Please explain.

Mike Walsh[br]Q. Karen Christensen: You have said that in today’s environment, “every company is an algorithmic company, whether it knows it or not.” Please explain.

Mike Walsh: We often assume that only purely digital companies like Google or Netflix can be called ‘algorithmic’ because their technology, infrastructure and customer experience are all based on data and algorithms. But the reality is that every type of organization, at every scale, will soon live and breathe by its capacity to leverage data, automation and algorithms to be more effective and create better customer experiences. Whether you run a big factory making automotive parts or a small dry cleaner in Brooklyn, your future is likely to depend more on how well you leverage the data and information generated by your activities rather than how well you manage the traditional levers of your business.

Q. Because of this, you say leaders need to become ‘algorithmic leaders’. How do you define that term?

An algorithmic leader is someone who has successfully adapted their decision making, management style and creative output to the complexities of the machine age. Algorithms are here to stay. The secret lies in knowing how to lead organizations that use and depend on them. The leaders we’ve looked up to and tried to emulate in recent years were all born and bred for a very different age. They are essentially products of an analog age, where you could predict with a greater degree of accuracy how your business was going to unfold. Imagine: You could actually think about putting together a five-year plan!

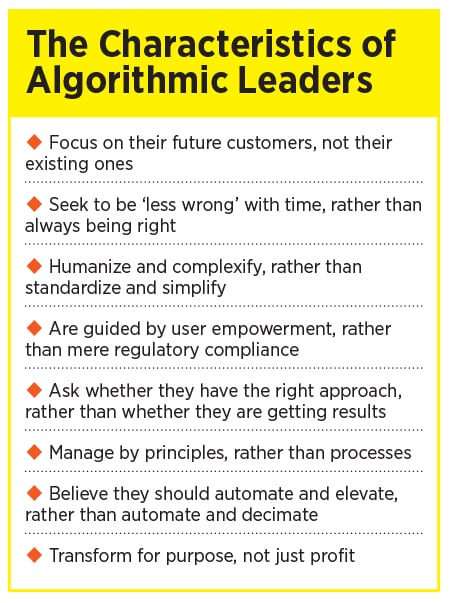

Algorithmic leaders are different in three key ways: attitude, hierarchy and tool kit. The attitude of an analog-era leader was all about being out in front, making all the big decisions and taking responsibility. Conversely, the algorithmic leader realizes that sometimes, the best decision is not to make a decision at all, and that your real work is often to design processes around you that enable other people to make the right decisions from moment to moment.

In terms of hierarchy, the analog leader sat at the top of a very primitive-style organization but the algorithmic leader is part of a large network of relationships and connections, where hierarchy isn’t as important. These leaders operate within what is more like an organic ecosystem.

Finally, their tool kits are very different. The way an algorithmic leader approaches problems and comes up with ideas is profoundly different, given that we are operating in an age characterized by automation and real-time data. Knowledge in an algorithmic organization lives everywhere—not just where the corporate directory says it belongs. The next great idea that will transform your business could be hidden in your server logs or in the field notes taken by an engineer. That’s why you have to enable your teams to self-manage and let go of the idea that you need to make all the important decisions yourself.

Q. You have said that one of the best examples of an algorithmic leader is Netflix CEO Reed Hastings. Talk a bit about how he personifies this leadership style.

It’s so interesting, because Reed wasn’t always an algorithmic leader. People often forget that Netflix started out by shipping DVD’s in the mail. They were actually much closer to a mail order business than a 21st century media company. But to his credit, Reed has always managed to be at the frontier of experimenting with new business models and new ways of making decisions. He fully recognized the power of data to inform every aspect of the way his company frames complex problems.

To me, Netflix’s greatest accomplishment is not that it put television onto a streaming platform it’s that it took the data from that streaming platform and used it to make decisions about which products to offer and what content to produce. That is the real difference between it and more traditional media organizations. Every aspect of how it thinks about audiences and how to plan its global expansion is driven by data and algorithms. When you are capable of knowing precisely what any of your millions of global customers are desiring at any point in time, how can you not see the world differently? And how can you not want to leverage machine learning and automation to fulfill those needs in a highly personalized way?

Like Reed Hastings, most of us started out as analog leaders. But if we haven’t already, we need to make a conscious decision to adapt and evolve—and recognize that the availability of data and algorithms must change our mindset about creating value for our customers. Q. While algorithms might not necessarily replace humans, you believe they increase the responsibility placed on us. How so?

Q. While algorithms might not necessarily replace humans, you believe they increase the responsibility placed on us. How so?

To be clear, an algorithm can never take the place of true leadership. We still need real-life humans who can interpret what the machines are telling us, decide whether those conclusions are appropriate and ethical, and orchestrate the capabilities of machines. The fact is, the most valuable thing that a leader can bring to the table in the 21st century is their humanity: their principles, ethics, and values.

Sometimes there is an assumption that automation will mean that we don’t need people any more. But, actually, what it really means is that we don’t need people to do things that are easily defined and repetitive. We actually need humans more than ever to deal with more nuanced, complex issues. There are real risks of algorithmic bias and discrimination and a potential for data to not be truly objective or to represent peoples’ interests. The potential for bias—and even evil—is extraordinary right now, which is why, in a way, automation is creating the potential for more complex work for humans to do.

Q. Talk a bit more about the downside of our increasing dependence on algorithms.

Unlike a human being, an algorithm will come to the same conclusion every single time, whether it’s Monday morning or Friday afternoon, before or after lunch, or after the algorithm has handled thousands of similar cases. However, that doesn’t make algorithms impartial judges. Quite the contrary. Algorithms are trained on data that is collected by and about humans. We—the humans—choose where the data comes from, what success criteria are used, and what ‘truth’ looks like. And in doing so, we embed our algorithms with all of our views, prejudices and biases. Ultimately, they are an expression of us and our world. So, while we may end up making fewer decisions in the future, leaders will need to spend more of their time designing, refining and validating the algorithms that will make those decisions instead.

Q. What does it mean for a company to ‘work backward from the future’?

Last year, I was totally inspired by a visit to Tokyo where I met with representatives from Softbank. This company is doing some extraordinary things right now. They’ve raised their massive vision fund and made huge bets. It’s hard not to see this as almost a sovereign state type of VC investing in the future. But when you look closely, you realize that their founder, Masayoshi Son, has a long track record of having a very strong personal vision of where human life is going to be in 50 years. He asks himself ‘what kind of technology, platforms and business models will need to exist in order for this future to take place?’ And then, he works backwards from there. If he can’t find these things to invest in today, he sets out to create them.

There is often a tendency to be very focused on your current customers. We still talk about the customer being king or queen but I argue that today’s customer is not king. The customer that is not even around yet is the one you should be focused on—because if you don’t set yourself up for a bigger horizon, by the time those customers come into the equation, you will have built a business that is not relevant to them.

Q. You believe that going forward, the greatest business value is likely to come from ‘new algorithmic experiences’. What do these look like?

If we were to look into a crystal ball at the year 2030, in many ways the physical infrastructure of the world will not be that different. Arguably, cars will still look like cars, and people will probably still be staring at some kind of screen for hours on end every day. Clothing might look a bit different, but essentially, the building blocks of human life will be pretty much the same. However, there will be something that is profoundly different, and that is your experience of living in the world.

In the next 10 years I think we’re going to see an acceleration of technologies that are better able to integrate our daily preferences to curate experiences and moments that are highly personalized throughout our day. This will touch on everything. It’s won’t be just about Netflix and Amazon being able to predict what you want to watch and read I’m talking about your healthcare provider, your financial services provider, your insurance provider, your utilities provider, and the way your home operates. Rather than just being responsive to what we want to happen, all of these services will anticipate things before we’ve even had to ask of them. That’s what I mean by an algorithmic experience. It’s where your entire experience with the world is essentially dictated by algorithms.

Q. Describe how your ‘Wheel of Algorithmic Experience’ works.

A useful way to start designing algorithmic experiences is to think about the relationships between three things: intentions, interactions and identity. Intentions are the often unarticulated needs or desires of a user or customer, which can be deduced from their behaviour Interactions are the method or manner by which you use a platform, product or service. And identity is the cognitive or emotional impact of the experience and the degree to which it has become integrated into a participant’s sense of self.

All three elements are connected and self-reinforcing: anticipating a user’s intentions allows you to create more natural interactions, such that the system itself becomes an extension of their identity. And the more an algorithm influences someone’s behaviour, the more it can anticipate their future intentions, making interactions more effortless, and son on.

Q. What are the dangers within algorithmic experiences?

Like video games or slot machines, algorithmic experiences can be designed to manipulate human behaviour by ‘weaponizing’ the reward loops in our brains that lead to addiction. Any time you are dealing with systems that learn to be progressively better at influencing behaviour, the risk for abuse is high.

Q. For most organizations, their customer of 2030 is alive today. What are the implications of this fact?

We seem to spend a lot of time worrying about Millennials. That has become synonymous with trying to engage with the future. But, I find it kind of funny, because by 2030, Millennials are going to be as old and as miserable as the rest of us. In fact, the generation we should be thinking about is the generation that essentially grew up in an algorithmic world: anyone born after 2007 will be coming into power in 2030. They’ll be becoming adults, joining the workforce and becoming consumers.

What makes this generation different—the generation I think will drive 2030 and beyond—is not that they’re grew up with mobile phones, it’s that they grew up with all of their experiences essentially being driven by data and algorithms. This is the generation that grew up not watching television, they grew up watching Netflix. They didn’t listen to the radio, they listened to Spotify. They didn’t hang out with their friends in public places they hung out on Snapchat and Instagram. This has huge implications as companies start to think about the customers they’ll be serving in 2030.

Q. Most of us recognize that algorithms are only as good as the data they are built with. What does great data look like? How can we know it when we see it?

The right data is not necessarily lots of data. We’ve gone through a major shift in our understanding of data. If you go back 20 years, people saw data as a cost. Even today, you probably get notes from your IT Manager saying ‘You’ve got way too much email go in and delete some of it immediately!’ It is only recently that we all decided that data is very valuable. Now, we want to keep everything, so there are these giant stores of data everywhere, and we seem to believe that at some point we will be able to sprinkle pixie dust on it and something amazing will happen. But when you look at the people doing interesting things with data and artificial intelligence, in many cases they are mostly teaching us about data collection. It’s not about having massive amounts of data. It’s about having the exact right sets of data that answer specific questions.

This makes me think of Andrew Ng, one of the pioneers of deep learning. When he was at Baidu, they would frequently start offering certain services just to collect a very specific type of data which they knew they needed. The need for specific data sets to train algorithms on was actually what guided the development of their platforms, rather than a specific business model.

Q. In a recent article you wrote that “technology has the potential to bring out the very worst in us.” Please explain.

Without careful consideration, the workplace of the future could end up as a data-driven dystopia. There are a million ways that algorithms in the hands of bad managers—and bad people in general—could do more harm than good. How about using an algorithm to set your work rosters so that the number of hours is just below the legal threshold for full-time employment? Or nudging people to work during the time they normally spend with their families by offering incentives? Or using sensors to monitor warehouse workers and then warning them when they take too long to stack a shelf?

Some of this is already happening. Amazon has received two patents for a wristband designed to guide warehouse workers’ movements with the use of vibrations to nudge them into being more efficient. And IBM has applied for a patent for a system that monitors its workforce with sensors that can track pupil dilation and facial expressions and then use data on an employee’s sleep quality and meeting schedule to deploy drones to deliver a jolt of caffeinated liquid, so employees’ workdays are undisturbed by coffee breaks. Many principles of Taylorism are being revived today with a digital or AI-based twist. And just as with Taylorism, reliance on algorithmic management may end up creating unease in the workplace and broader social unrest.

Q. In the book, you encourage leaders to think like computers. Aren’t there enough computers out there? What’s wrong with thinking like a human?

I actually encourage people to embrace computational thinking, which is slightly different. Computational thinking is about approaching problems and making decisions in a structured way that allows you to ultimately leverage technology, data and even automation to be more effective.

Getting kids prepared for the algorithmic age is not about teaching them how to use Twitter or Instagram they already know about such things better than us. It’s not even about teaching them programming. What we actually need to do is teach kids to be ready to engage with the world and to approach decisions and problems in a way that leverages technology to make people more effective.

Whether you’re a programmer or an executive, this kind of thinking is invaluable. The rockstars of the 21st century will be leaders who can master both an understanding of human complexity and a flair for computational thinking. While machines will get dramatically better at extracting insights from data, spotting patterns and even making decisions on our behalf, only humans will have the unique ability to imagine innovative ways to use machine intelligence to create experiences, transform organizations and reinvent the world.

Futurist Mike Walsh is the author of The Algorithmic Leader: How to Be Smart When Machines Are Smarter Than You (Page Two Books, 2019). Based in Sydney, Australia, he is the CEO of Tomorrow, a consultancy that designs organizations for the 21st century, with clients from the Fortune 500. Each week he interviews provocative thinkers, innovators and troublemakers on his podcast, Between Worlds.

First Published: Jan 14, 2021, 13:04

Subscribe Now