Lost diaries of war emerge, more relevant than ever today

Volunteers are helping forgotten Dutch diarists of WWII to speak at last. Their voices, filled with anxiety, isolation and uncertainty, resonate powerfully today

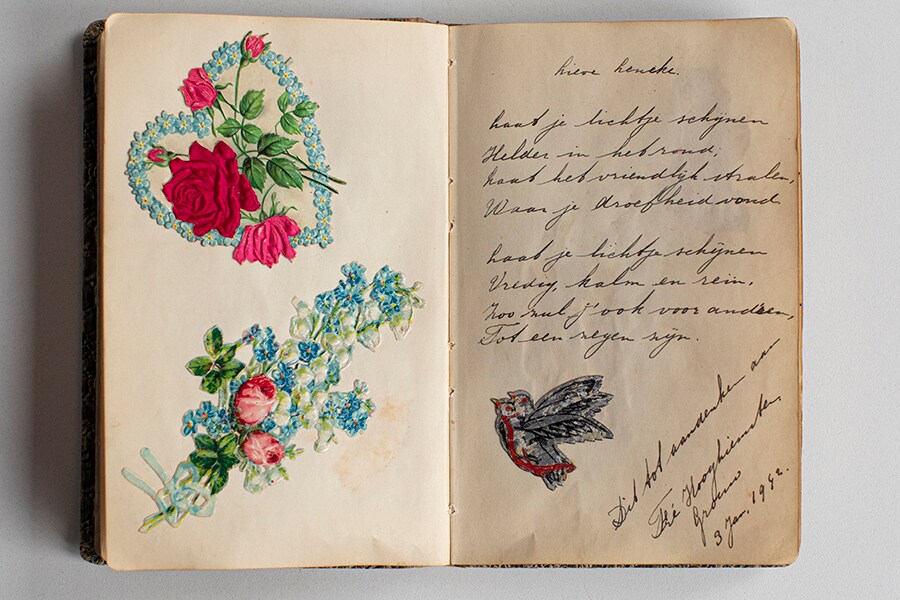

The diary of L. Bijlsma, who had friends and family writing poems in her album during World War II, Almere, Netherlands, March 5, 2020. After the Netherlands was liberated in May 1945, diarists showed up at the National Office for the History of the Netherlands in Wartime, with their notebooks and letters in hand, and with more than 2,000 diaries collected, the Dutch have launched an effort to transcribe the handwritten or typed pages into digital documents, ready for posting on the archive’s website. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/The New York Times)[br]Anne Frank listened in an Amsterdam attic on March 28, 1944, as the voice of the Dutch minister of education came crackling over the radio from London.

The diary of L. Bijlsma, who had friends and family writing poems in her album during World War II, Almere, Netherlands, March 5, 2020. After the Netherlands was liberated in May 1945, diarists showed up at the National Office for the History of the Netherlands in Wartime, with their notebooks and letters in hand, and with more than 2,000 diaries collected, the Dutch have launched an effort to transcribe the handwritten or typed pages into digital documents, ready for posting on the archive’s website. (Ilvy Njiokiktjien/The New York Times)[br]Anne Frank listened in an Amsterdam attic on March 28, 1944, as the voice of the Dutch minister of education came crackling over the radio from London.

The minister, part of a government in exile that had fled the Nazis, appealed to his compatriots: Preserve your diaries and letters.

“Only if we succeed in bringing this simple, daily material together in overwhelming quantity, only then will the scene of this struggle for freedom be painted in full depth and shine,” the minister, Gerrit Bolkestein, said.

His words inspired Frank to set aside “Kitty,” the diary she had created as a personal refuge, and to begin a revised version called “The Secret Annex,” which she hoped to publish.

Other Dutch men and women were listening, too — thousands of them — and after the country was liberated in May 1945, they showed up at the National Office for the History of the Netherlands in Wartime with their notebooks and letters in hand. More than 2,000 diaries were collected, each a story of pain and loss, fear and hunger and, yes, moments of levity amid the misery.

But unlike Frank’s diary, most of these accounts never surfaced again. Scholars read them once to inventory them, then shelved them — powerful but mute witnesses to the horrors of war. Now, though, the Dutch have begun an effort to transcribe the handwritten or typed pages into digital documents, ready for posting on the archive’s website. More than 90 have already been fully transcribed.

“The most valuable diaries are the ones where they wrote about their own feelings, or conversations they had on the street or with family, or how they felt about the persecution of the Jews,” said Rene Kok, a researcher with the Dutch archive. “The best diarists are the ones with courage.”

Here are edited excerpts from several diaries that track the course of the war, beginning with the Nazi attack. Many people began their diaries that day, long before the radio address, as they worked to record their experiences in the most personal of terms. Their words, filled with the anxiety born from illness, isolation and uncertainty, resonate powerfully today in another unsettled time.

THE INVASION

It began in the early morning, a sneak attack as German Luftwaffe paratroopers jumped from planes over selected targets across the country. Four days later, Rotterdam’s center was bombed to the ground, killing 800 people. The Dutch royal family fled for Britain. The Dutch Army capitulated on May 15.

Elisabeth Jacoba van Lohuizen-van Wielink, 49, began her diary immediately and ultimately wrote 941 pages. She was the wife of a pharmacist and optician, who owned a grocery store in Epe, near Apeldoorn.

May 10, 1940

Last night the roar of aircraft kept waking us up. First at around 2 o’clock, later at around 4. The second time, I got up to take a look, but couldn’t see anything. I thought they might be German or English planes, heading for their enemies. I tried to sleep again. Though the noise never stopped, I was suddenly woken up by shouting. At first, I thought it was the people working at the house next door, but then I heard Mies van Lohuizen suddenly say: “They can’t hear anything, I got up and heard, War! Can’t you hear those airplanes?” I found it hard to believe, but woke up Cees, who immediately turned on the radio, and then we heard several messages from the air force. A moment I’ll never forget. I’d always assumed they would leave us alone. We had been neutral until the end, and good to the Germans. We heard shouting, too. For a minute, we felt like we were paralyzed, and my first thought was, poor soldiers, there will be bloodshed.

After we got dressed, we quickly packed what needed to go or be destroyed. Such as the alcohol, which definitely had to be taken. Most of it was sent a few weeks ago. The workmen, who were at home, were also asked to come. They were equally upset. War. We couldn’t believe it. Everything in nature was so beautiful, and that day in particular was sunny and bright.

May 14, 1940

At 7 o’clock, suddenly an extra message on the radio, a moment I’ll never forget. The commander in chief had decided to cease all hostilities. Rotterdam was as good as destroyed by the bombardments if they didn’t cease fighting, The Hague, Amsterdam and Utrecht would meet the same fate. I was so overwhelmed, I wept. We weren’t free anymore, and this, if we understood correctly, as a result of betrayal by our own people. We couldn’t believe it, yet it was true. Everyone was glad no more people would be killed, but still. To become part of Germany, how awful! What will the future bring? Poverty for our country. A heavy ordeal for everyone and an uncertain future.

THE SYMPATHIZER

A Dutch counterpart to the German Nazi party, the Nationaal-Socialistische Beweging, or NSB, was active in the country for several years before the Nazi invasion. When the Germans occupied the country, many Dutch members of the movement became collaborators.

The writer, a woman from The Hague whose name was not disclosed by the archive because of privacy concerns, sympathizes with the Germans and is upset that the royal family has fled.

May 15, 1940

The (Dutch) air defense people ordered us to build barricades in the street in front of our house. Everyone had to help loosen tiles, stack them and take out all kinds of junk. I even saw parts of bed frames in the street. It was just ridiculous, absolutely laughable it looked as if it’d been done by children. Later, we heard that citizens weren’t even allowed to do this. Anyway, what were these barricades to the Germans? They would easily push everything aside with their powerful vehicles. Now they are proper soldiers not like our boys, who couldn’t control their nerves and just kept shooting at random.

The way the Germans acted was so proper, so magnificent, so disciplined they command nothing but respect. The locals could learn a lot from the Germans. Just look at them marching by, on foot or on horseback or with their guns, looking so beautiful, so healthy, and with such cheerful faces they’re big and sturdy and very neat, making you think, inadvertently, some army the Dutch have! The people here are so rude and impolite, while the Germans are so proper and polite! It’s easy to see the difference.

This is the Netherlands, how dare they fight such a powerful, strong people? No wonder they had to give up fighting after four days, the difference was too great. And what about our officers — well, not all of them, of course — stirrers and rabble-rousers. I’ve always been one for the military and considered them our protectors, but I’ve had more than enough of them. I have no respect for them anymore. They have really frightened me. When I think of everything that’s happened, I feel so embittered. I would love to let them have it. I’m livid, my heart is on fire. But Nat. Socialism says we’re not to repay evil with evil! How is this possible if you harbor feelings of revenge for all the humiliation we’ve had to endure? It’s nearly impossible, yet we must.

We need to rebuild, that’s what’s required of us. The fact that there are still people who support the Queen is incomprehensible to us a queen who has fled her country because she feared for her life, who has abandoned her people in need who has let her soldiers bleed to death and sought refuge herself! Surely, a mother doesn’t abandon her child? The Germans wouldn’t have harmed her they are much too honorable for that.

THE STRIKE

In 1941, when the occupiers first began rounding up and deporting Jews, members of the Dutch Communist party, which was illegal at the time, called for a protest strike in response. On Feb. 25, trams in Amsterdam stopped working. Dockworkers walked off the job. Many shops closed in solidarity.

Jan Kruisinga, a notary and poet from Den Helder, wrote about the strike in his 3,600-page, multivolume diary.

Feb. 27, 1941

On Tuesday and Wednesday, there was a general strike in Amsterdam. There was nothing about it in the papers, but we heard the first rumors from travelers on Wednesday morning, and they were confirmed in the letters from the capital that we received today.

The cause of the strike seems to have been the fact that the “Green Police” [the German Ordnungspolizei, who wore green uniforms] and the WA [Weerbaarheidsafdeling, the military wing of the NSB] or “Dutch SS” took all male Jews aged between 20 and 35 from their homes in the Jewish area, herded them together on Waterlooplein [Square, in the east of Amsterdam], loaded them onto trucks and took them in the direction of Schoorl or Wieringermeer. There had been tension before, apparently, as a result of the requisition of workers for Germany at one of the Amsterdam shipyards, after which all shipyards and dockyards were telephoned and urged to immediately down tools.

This issue seems to have been settled by the German authorities, but the imprisonment of the Jewish population was not accepted by their “Aryan” fellow-townsmen the Jordaan and Kattenburg areas turned out soon, improvising a kind of oranjefeest [Orange celebration, that is, a national celebration] on Dam [Square, in the center of Amsterdam] — which is forbidden at the moment. Signs (“de Joden vrij, dan werken wij” — free the Jews, then we’ll work) were used in the city to urge workers not to go to work on Tuesday. Which is what happened: There were no trams or buses, and most public services — the gas and water company in particular — were largely or entirely suspended. It was eerily quiet in the city at night, only pistol shots could be heard from time to time. I don’t know yet whether there were any casualties and if so, how many.

Some 300,000 workers joined the strike in Amsterdam, where there was marching in the streets. The next day, workers in Haarlem, Hilversum, Utrecht and other cities joined in. Clashes with retaliating German forces in various places left nine dead and 24 wounded.

THE CROWDING

Wartime conditions were particularly gruesome for Dutch Jews. Because the sick were among the first to be carted off in transports to concentration camps, people who were ill often piled into the homes of able-bodied relatives, creating cramped households.

Mirjam Bolle in Amsterdam discusses the many people her family is attempting to house in this excerpt from her diary of letters to her fiancé that she wrote but never mailed. The letters were published in English in a book, “Letters Never Sent” by Yad Vashem in 2014.

Feb. 23, 1943: Half-past midnight

This is no life, but hell on earth. My hands are trembling so much I can barely write. This is all getting too much. This is more than anyone can bear. Another transport is leaving this evening. I had planned not to go to bed too late. Aunt Dina is staying with us at the moment. I already wrote to you that she stays at our house during the day because she has been left at home on grounds of illness and now she fears being taken away, which is what happens in all of these cases. At home on Saturday morning, she got such a bad crick in her back that she couldn’t move, not even in bed. It was awful, because it meant she wouldn’t be able to come and stay with us on Monday, as Jews aren’t allowed in taxis.

We decided to wait and see what Sunday would bring, but her condition didn’t improve. She was then brought to our house by private patient transport, that’s to say on a stretcher in an ambulance. It was terrible to see her stretchered in like that, but we still laughed, because fortunately, there’s nothing wrong with her apart from her bad back.

When the ambulance pulled up at their doorstep, neighborhood women rushed out to ask what was happening. Lea said: “My aunt has become unwell, and because she can’t stay with us we have to have her picked up in this way. And would you please excuse me now, for Mother isn’t at home either.” This is the kind of act you have to put on because it would be unwise to reveal too much. Well-intentioned gossip could fall on the wrong ears. Aunt Dina is staying with us now and is already doing much better. She sleeps in Grandmother’s bed in the passage room. Since Friday, Mr. Vromen has also been living with us. He is sleeping in the back room, our former living room.

THE CHERRY ORCHARD

As the raids on Jews continued, the Dutch who were not Jewish confronted the disparity between their circumstances and those of their fellow citizens. For one family, the contrast became apparent during a 1943 train trip to an outing in an orchard, a venture disrupted by a raid in Amsterdam that rounded up more than 2,400 Jews for deportation.

The diary was created by Cornelis Komen, a 48-year old salesman in Amsterdam for an English asbestos company that was shuttered during the occupation.

June 20, 1943

Many people on the train don’t even know what’s going on in Amsterdam. The last Jews are being rounded up. Herded together and taken away like cattle. From hearth and home to foreign parts. First, they’re taken to Vught, then they’re transported to Poland — oh, the misery these people must be going through. Separated from their wives and children. They may not be a pleasant people, but they’re still human beings. How can the Good God allow this?

But we’re on our way to Tiel. The train is packed, and in Utrecht another bunch piles in. But people are in a good mood, because everyone’s getting out today, to eat or buy cherries. In Geldermalsen we change trains to Tiel. Even more crowded. The carriages are bursting at the seams. But we’re getting there, and Van Dien is waiting for us. How peaceful it is, this small provincial town. When we arrive, there’s breakfast on the table. As always, this is such a lovely surprise to us. Smoke-dried beef and rusks.

Afterward, we have some coffee, and then we’re off to the cherry orchard. We need to walk three quarters of an hour. It’s beautiful in the Betuwe [a fruit-growing region]. We’re surrounded by nothing but rustling wheat fields, interspersed with beautiful orchards. Apples here, pears over there, and sometimes plum or cherry trees. One even more beautiful than the other. Then we reach Farmer Kerdijk. V. Dien immediately orders a box of 7.5 kilos of cherries. We sit ourselves down and start to eat. The box is empty in less than half an hour, but then we’re fed up with cherries. That’s the problem if you have too much of something, it soon starts to pall. We run a race. V. Dien loses to me. Wim beats Bert. The Willinks are the champions. Then we do some boxing. And then the boys try to wrestle v. Dien down to the ground. Not a chance. He breaks into a sweat. It’s lovely getting tired this way. How wonderful life is.

While in Amsterdam, the Jews are herded together like cattle. Carrying their bundles on their backs. Their blankets. They packed their things days in advance. Still, how hard their departure must have been. Parting from their familiar living rooms, their friends and acquaintances. While we are eating cherries, one basket after another. Lazing around. How lovely this place is.

THE INTERNMENT

Most of the Jews who were rounded up joined Roma and Sinti people at Westerbork, a transit camp in the northeast Netherlands. Most were then sent on to Nazi concentration and extermination camps farther east in Poland, Germany and Austria.

Philip Mechanicus, a journalist in his 50s, was arrested in September 1942 for not wearing a Star of David on a tram and was sent to Westerbork. His diary, which was published in English in 1968, documented camp life with precision. In it, he often spoke of the transports that left every Tuesday, carrying 1,000 to 3,000 people to even harsher fates.

May 29, 1943

It feels as though I’m an official reporter reporting on a shipwreck. We’re in a cyclone together, aware that the holed ship is sinking slowly and trying to reach a harbor, but this harbor seems far away. I’m slowly beginning to realize that I haven’t been brought here by my persecutors I’m on this journey voluntarily to do my work. I’m busy all day long, not bored at all, sometimes I almost don’t even have enough time. Duty calls and labor is noble. I spend much of the day writing sometimes, I start as early as 5:30 in the morning, sometimes I’m still at it after bedtime, summarizing my impressions or experiences of the day.

June 1, 1943

The transports continue to evoke disgust. People are actually taken in animal wagons intended for transporting horses. And the deported no longer lie on straw but among their bags of food and small pieces of luggage on the bare floor — including the ill, who were given a mattress only last week. They’re gathered at the exits of their barracks and taken by OD men [OD stands for ordedienst, the camp’s police force required to keep order] in rows of three to the train on the Boulevard des Misères, in the middle of the camp. The train: a long, mangy snake of filthy old wagons splitting the camp in two. The Boulevard: a deserted area guarded by OD men to keep redundant onlookers at bay. The exiles carry a bread bag strapped to the shoulder and hanging on their hips, as well as a rolled-up blanket hanging from the other shoulder by a rope and swinging on their backs. Dirty emigrants who own no more than what they’re wearing and what is hanging from them. Men: quiet, faces drawn women: often sobbing. The elderly: stumbling down the bad road, sometimes through mud puddles, buckling under their heavy load. The ill on stretchers, hauled by OD men.

Jan. 25, 1944

A transport of a thousand people left for Auschwitz in a howling storm and pouring rain. In animal wagons, yet again. The majority was from the S barracks: 590 people. The rest, young men of the Aliyah, old men from the hospital and 31 young, nameless children from the orphanage whose parents are either absent or have already been sent to Poland. Among them was a 10-year-old boy with a temperature of 39.9°C [103.82°F]: one-tenth of a degree short to be one of the lucky ones who are categorized (by the Germans) as Untransportfähig [untransportable]. The removal of punished or unproductive elements who were just a burden on the camp budget. People still don’t know what happens to the deported Jews in Poland. They curse the National Socialists and try to find terms to express their feelings of disdain, disgust, horror, and hate, but no one finds the right words.

“When, oh when will the war be over? When will this misery of the weekly transports come to an end?” the women lament. “The war is going well! But there’s a transport every week,” the men say, mocking them, trusting the war will soon end in victory for the Allies. Winter is progressing, and people fear that if there’s no decisive battle this winter, the war will drag on all summer, and there won’t be a single Jew left on Dutch soil. Hope alternates with fear: Where are we heading? What is our fate? What is our future?

THE LIBERATION

The war in the Netherlands ended May 5, 1945, when Canadian and German commanders reached an agreement on the capitulation of German forces.

Anton Frans Koenraads, a 39-year old teacher in Delft, the hometown of Johannes Vermeer, is among those who are slow to trust that the war is really over.

May 6, 1945

The mayor gestures for calm. He is about to address the citizens. I notice that he’s shouting, but the only words of the entire proclamation that I can hear are “fellow-townsmen and women” and, much later, “we’re free.” Those who are standing near him can hear more, while we just join in the repeated, spontaneous bursts of cheering. Finally, we all sing the old Wilhelmus [the Dutch national anthem], moving us all, and when the line “drive out the tyranny” resounds, it seems as if a long pent-up feeling of hatred erupts in people.

It’s real now, though, and while I’m writing this, I try to realize what it means. But it’s so hard to put down in words. Five years of having lived under the yoke of a ruthless enemy aren’t erased in just a few minutes. But what I can grasp, is that:

Soon, there will be food

There will be gas, electricity, and water

There will be fuel

Trains and trams will run again

Our men will return from G, where they have been living as forced laborers for years

Our prisoners of war and students will also return

I can walk down the street at any time, day or night

The blackout paper can be removed everywhere

I don’t need to be frightened when a car is driving down the street

Or when someone rings the doorbell late at night

There will be newspapers again

Depending on one’s taste, the cinemas, dance halls, cafes, concert halls, theaters, and music halls will open again

If torture hasn’t resulted in death, families will be reunited

No Westerbork, Amersfoort, Vught [concentration camps in the Netherlands] should ever be built again for anyone other than the G

After destroying Japan, humanity will find the means to ban war once and for all

I will be free to listen without fear to any radio channel I want to listen to

There will be regular school and work hours again

All these things are running through my mind. Not all at the same time, not one by one. Sometimes I become aware of a few of them, which remain for a moment, then recede until another one comes flashing through my brain.

I thought I could end this diary with a sentence like: The first Canadians, still smudged with the smoke of battle, are turning the corner of our street. But things have turned out differently. We’re still cheerfully awaiting their arrival.

I expected the end would bring relief, like taking off a lead suit. Things turned out differently yet again. I find it difficult to get used to the idea that we really are free now. Every time I think of how many things that used to frighten me have now disappeared, my heart is touched with happiness.

Thus, this diary is coming to an end. In it, I’ve tried to convey what has been on my mind during these recent months of the war. It’s by no means objective. Objectivity is a matter of time, of history, and of [one’s] point of view.

Later history books could — mind you, could — be objective. But this diary can’t possibly be. It has been written as events were unfolding, sometimes without knowing the causes, even, of the facts that I have described, nor of their place in the bigger picture. Some of the facts may have been incorrectly motivated, but they really did happen. Sometimes I fear that I won’t be believed, because later generations simply won’t wish to accept what’s described in these pages, yet I swear on everything that’s dear to me that none of the events are untrue. Everything that’s been written down was “hot off the press,” I would say.

I’ve had the painful privilege of having experienced an “all-out war.” That is behind us now. With all the strength that’s in us: Let’s go for “all-out peace.”

THE AFTERMATH

Diaries, once considered too subjective to be historical sources, are now regarded as more reliable, experts say, although primarily for their ability to depict how people thought and felt.

Of the diarists, only Bolle, who is 102 and lives in Israel, is still alive. She was sent to a concentration camp during the war but was one of a handful of prisoners in Bergen-Belsen traded for the release of German POWs in Palestine during the war.

Mechanicus was also put on a train to Bergen-Belsen. From there he was transferred to Auschwitz, where he was shot on arrival, on Oct. 12, 1944.

Kruisinga survived the war and later lived in Vriezenveen, a town in the Netherlands, where he died Feb. 1, 1971, at the age of 75.

Van Lohuizen-van Wielink became active in the resistance and is credited with saving the lives of 72 Jews she, her husband and son were arrested and imprisoned for this work but survived the war.

Archivists do not have a sense of what happened to the other diarists featured here, but they hope to keep their memories alive through the work of more than 130 transcribers like Josine Franken, a retired speech therapist.

She is now transcribing a diary, her fourth, that was written by Arnolda Johanna Geertruid Huizinga-Sannes, the wife of a church vicar from Velp, a town near Arnhem and near the front lines during the final stages of the war. Huizinga-Sannes hoped her daughter might be able to read the diary after the war.

“She had twins, a daughter and a son,” Franken said of Huizinga-Sannes. But the son died shortly after the war, and her daughter became mentally ill.

“So then when you read all the woman writes, knowing that her daughter will never read it,” she said, “and knowing that her two children are lost to her, it’s very moving. It gives you such a feeling of compassion.”

First Published: Apr 18, 2020, 10:00

Subscribe Now