Flipkart, pound of flesh & Tiger's meaty bets

Although Flipkart is the blockbuster exit for Tiger Global in India, it has made handsome returns from Delhivery, PB Fintech and Zomato too. But it will be tough to find another Flipkart in its curren

Tiger doesn’t talk. But when it does, the roar reverberates. “Returns on capital in India have sucked historically," Scott Shleifer reportedly lamented on an investor call this February. With global internet leaders—Google, Facebook, Alibaba or Tencent—revenue for Tiger got bigger than cost more than a decade ago, the partner at Tiger Global elaborated. With a great legacy of 17 to 18 years of materially profitable internet companies, returns on equity and returns for investors have been really high. “But that did not happen in India," he reportedly said on the call, as quoted by TechCrunch. “Returns on capital for investors like us have been below average… way below," he reckoned. “But that’s the past."

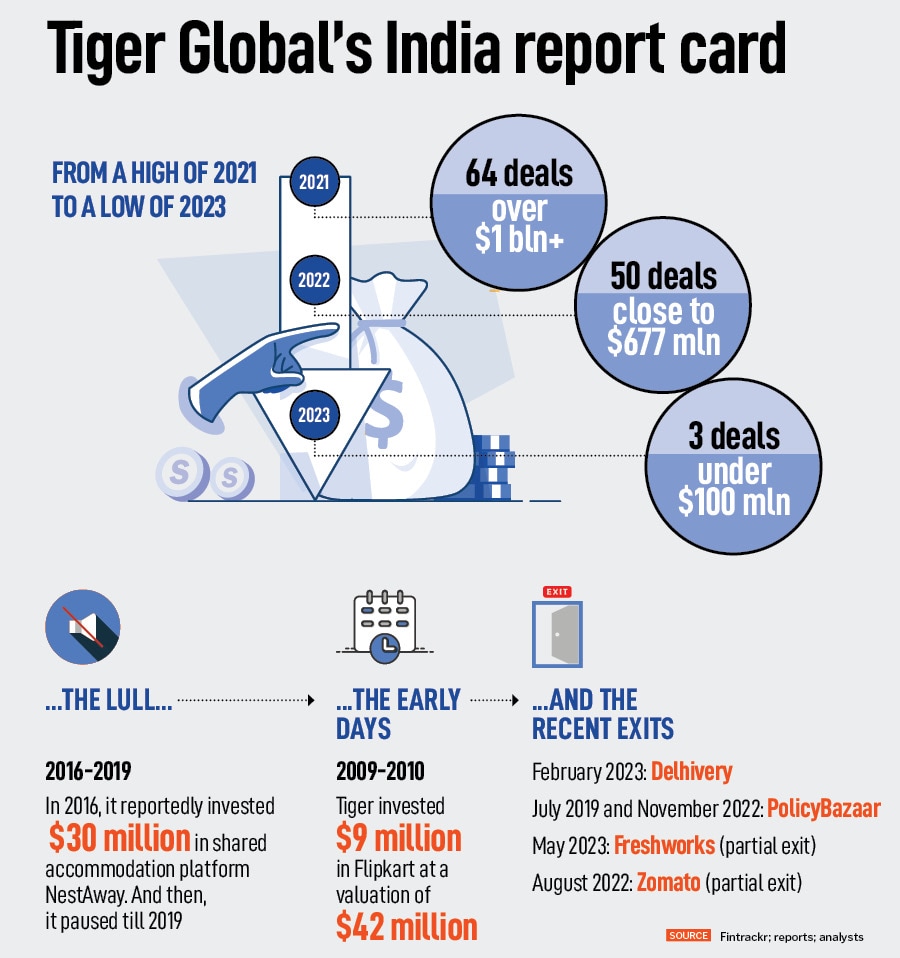

Five months later, the present indeed is a stark and refreshing contrast. An investment made in ecommerce firm Flipkart way back in 2009-10—over the next decade, Tiger Global ended up pumping in around a $1 billion in the etailer—has reportedly fetched the American investment and hedge fund biggie around $3.5 billion. The exit happens to be Tiger’s biggest in India. No wonder, Shleifer quickly switched his mood—lament to exuberance—and dwelled upon the potential of India during the investor call mentioned above. “We think it [India] will be the best place to invest," he underlined, adding that the fund bought 16 to 17 percent of Flipkart for $8 million in 2010, 10 percent of Infra.Market came for $8 million, and a third of Upstox for $50 million. “Both the firms raised capital in their most recent rounds at over $2.5 billion valuation," he stressed.

Back in India, analysts and industry watchers decode Shleifer’s mood, and reckon that a “Flipkart-kind of exit" must be viewed as an exception rather than the rule for Tiger. They start by pointing out one of the big misses of Tiger in the ecommerce space. In 2015, Flipkart rival ShopClues raised $100 million in its Series D round led by Tiger Global. Started in 2011, ShopClues had scaled at an aggressive pace, and reportedly had 40 million visitors per month in 2015. The etailer also claimed to have over 1 lakh sellers, 10 million products, and a reach across 25,000 cities.

The following year, in 2016, ShopClues turned unicorn. It was valued at $1.1 billion, and Tiger participated in the new funding round. Widely dubbed as the “next Flipkart", ShopClues, though, flamed out over the next few years. In 2019, it was sold to a Singapore-based company in a fire sale. In FY20, ShopClues had an operating revenue of Rs 89.1 crore and a loss of Rs 51.5 crore. Tiger’s big bet, and hunt for another Flipkart ended in a dampener.

Meanwhile, three months later in India, there was no respite. NestAway—a startup in shared accommodation backed by Tiger—was sold at a 95 percent valuation haircut. The Bengaluru-based startup had raised $110 million, was valued at $220 million, and sold for $11 million. “It was a promising startup," says one of the venture capitalists (VCs) who invested in a much smaller shared accommodation rival which shut shop a few years ago. “NestAway was another aggressive bet of Tiger, and it was expected to perform well," he says, requesting anonymity. Earlier this year, GoMechanic—yet another startup backed by Tiger—was sold in a slump sale. In deep trouble due to alleged financial irregularities, co-founder Amit Bhasin took to LinkedIn to explain what went wrong. “We made errors in judgement as we followed growth at all costs, including financial reporting, which we deeply regret," he reportedly underlined. Tiger, says the VC quoted above, has more trouble in store.

Take, for instance, the edtech space, which has dramatically crashed over the last 18 months. Tiger’s three meaty bets—Byju’s, Unacademy and Vedantu—have laid off thousands, and are trying hard to survive the funding winter as revenue dips and students flock to schools, colleges and offline coaching centres. “Where is the next Flipkart?" asks another VC. Tiger, he reckons, has been in exit mode in India. Over the last 18 months or so, he points out, the global investment major has made exits from the startups that got listed. It has exited from PB Fintech, the parent entity of PolicyBazaar it made a partial exit from Freshworks and brought down its stake it has also exited Delhivery. The interesting part is that it made money in all these exits.

Take, for instance, the edtech space, which has dramatically crashed over the last 18 months. Tiger’s three meaty bets—Byju’s, Unacademy and Vedantu—have laid off thousands, and are trying hard to survive the funding winter as revenue dips and students flock to schools, colleges and offline coaching centres. “Where is the next Flipkart?" asks another VC. Tiger, he reckons, has been in exit mode in India. Over the last 18 months or so, he points out, the global investment major has made exits from the startups that got listed. It has exited from PB Fintech, the parent entity of PolicyBazaar it made a partial exit from Freshworks and brought down its stake it has also exited Delhivery. The interesting part is that it made money in all these exits.

A bitter funding winter and the need to show liquidity and results, point out experts, have forced Tiger to take a step back. “It’s a cooling-off period for Tiger Global, and it’s not unusual," reckons Jai Vardhan, co-founder and CEO at Entrackr, a media venture tracking startups and internet economy in India. After writing over a dozen cheques in 2015, Vardhan underlines, Tiger didn’t invest in a single startup until 2018. “In 2019, the fund started re-investing and participated in over two dozen companies’ unicorn rounds," he says, adding that slowing down of investment in India—just three deals so far in 2023—has been triggered by a liquidity crunch. “Issues of corporate governance in its portfolio companies such as BharatPe and GoMechanic might be one of the reasons for a cautionary approach by Tiger."

With Razorpay, Spinny, Infra.Market and Ofbusiness expected to hit the public markets over the next few years, can Tiger find its next Flipkart? “It won’t be easy," reckons Vardhan. Reasons are many. Most of the low-hanging fruit have been plucked in horizontal e-commerce platforms, edtech is in turmoil, there is still an element of unpredictability when it comes to fintech, and Tiger’s bets in other segments are not substantial. Even where Tiger has an early exposure, Ola, it’s too early to say how the electric venture will pan out for the company. “Flipkart happened some 13 years ago. Delhivery, PB Fintech and Freshworks too are dated bets," says another VC, requesting not to be named. “Still there are no signs of the next Flipkart," he says, adding that the current state of its portfolio is the harsh reality it has to live with in India. Seems like the next big roar will take some time.

First Published: Aug 01, 2023, 14:52

Subscribe Now