From noun to verb: Can Dunzo do a Zoom?

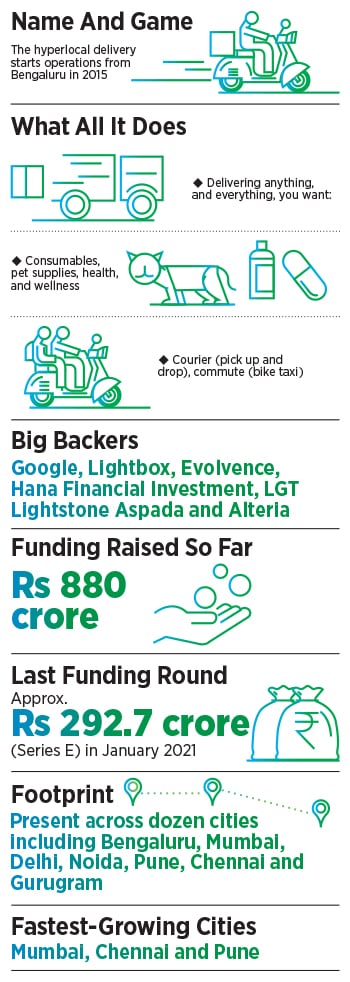

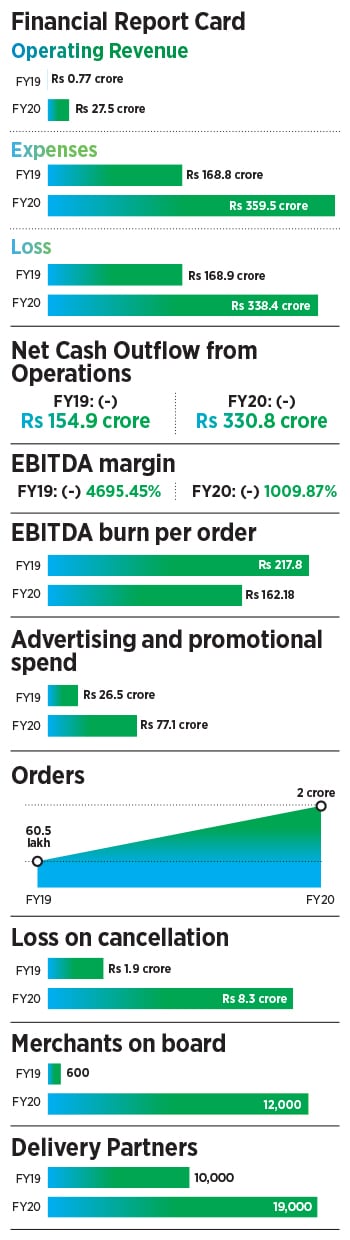

It has raised around Rs 880 crore in six years, earned Rs 27.5 crore but lost Rs 338.4 crore. Critics may scoff, but Dunzo's backers aren't complaining, and co-founder Kabeer Biswas is chilled out. Me

Kabeer Biswas, co-founder, Dunzo

Kabeer Biswas, co-founder, Dunzo

Image: Selvaprakash Lakshmanan for Forbes India

“Itna kya serious hai baap. Thoda chill ho na. Log hain, bolenge” (“Why are you so serious, man? Relax a bit. People will say what they have to”).

Kabeer Biswas has the swagger of a man who appears cut off from the outside world, especially if the outside world doesn’t fit into his ‘world’. “If you are a consumer,” Dunzo’s cofounder underlines, “I will fall over backwards to solve your problem. But if you are not, I don’t care about your views,” the 35-year-old entrepreneur says, flashing a disarming smile.

It’s a chilly Friday morning in New Delhi, we are just five minutes into the Zoom interview call in January. Dressed in a Dunzo-branded blue jacket, Biswas turns up the heat with his blunt take on a subject that has been used to wage a relentless attack on the CEO of the Bengaluru-based hyperlocal delivery startup over the last two years: its losses. In 2019, the critics ruthlessly exposed the gross mismatch between the topline and the bottom line of the Google-backed venture. A staggering loss of Rs 168.8 crore on an operational revenue of a paltry Rs 77 lakh didn’t seem to make any sense.

A year later, in FY20, there was a growth surge. Revenue was now up at Rs 27.5 crore. But so was the loss—more than two times that of the previous year, at Rs 359.5 crore.

Founded in January 2015, Dunzo has loaded itself with $121 million (around Rs 880 crore) from a battery of marquee investors such as Google, Lightbox, Evolvence Group, Hana Financial Investment, LGT Aspada and Alteria Capital. The six-year-old venture happens to be Google’s first direct investment in a homegrown startup in India when it reportedly led a $12 million funding round in December 2017.

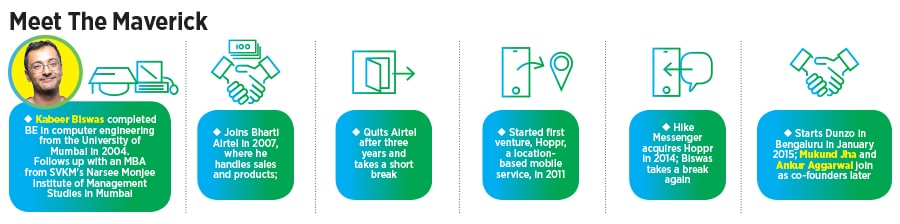

Is the burn going to be worth it? “No one thing ever makes us,” says the bespectacled founder. “And no one thing ever destroys us,” adds Biswas, who started his professional innings by joining Airtel in 2007 after an MBA from Narsee Monjee Institute of Management Studies in Mumbai. After a three-year marketing and product stint at the telecom major, Biswas started his first startup Hoppr, a location-based mobile service in 2011. A hefty seed round—$5 million—led to the first mistake. “Pehli cheez office banwaai thi. (First thing I did was to open an office),” he smiles, adjusting his white wireless earbuds.

The lesson was as quick as the error for the first-time entrepreneur. “I figured that you shouldn"t give too much money to people who don"t know what to do with the capital,” he laughs. Over the next three years—which included a couple of pivots, a few more rounds of capital, and a few more mistakes—the company was bought by Hike Messenger, which recently reportedly shut down. Biswas traces the roots of the follies of his first venture to his formal education. Starting companies at the age of 27 in India, he explains, is a hazardous thing. “It’s hazardous because there"s so much unlearning to do,” he quips. “Formal education doesn’t teach us to question things, he adds.

Along with Biswas, his backers, too, seem unperturbed by the sea of red on the bottom line. Sid Talwar, partner at Lightbox Ventures, dishes out two broad reasons. The first is the personality of Biswas. “What got me excited from the beginning was that, apart from other things, Kabeer is genuine to the core.” Lightbox invested in the company in 2019. There may be a lot of people with energy and great vision, Talwar underlines, but he (Biswas) is somebody who you would want to root for. “He is not selling you a story because he is a salesperson. He is selling you a story because he is trying to do something different.”

Over the last two years, Talwar’s admiration for Biswas and his business model has grown manifold. “Investors don’t have a problem, Kabeer has a sound business strategy, and consumers love the service,” he says curtly. “I don’t know why you guys keep harping about the losses,” he quips. Lightbox’s bold bet—Talwar though prefers to call it a calculated and measured assumption—on Dunzo also stems from the opportunity, backed by performance, that the startup has in the sector it operates.

Let’s start with the numbers beyond the top and bottom line. Burn per order at the EBITDA (Earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortisation) level came down from Rs 217.8 to Rs 162.18 number of orders serviced leapfrogged from 6.54 million to 20.3 million delivery partners grew from 10,000 to 19,000 and the merchants base leapfrogged from 600 to 12,000. Dunzo gets a thumbs up from Talwar. “I am not gambling on Kabeer or Dunzo,” he says, explaining Dunzo’s calculated play.

The startup could easily have been in 100 cities, but the fact is it is still not present in some of the top cities. “In fact, it’s not even there in South Mumbai,” Talwar adds. Can you imagine a startup that has raised over $100 million and is not present in South Mumbai, he asks. Kabeer, he points out, is building the largest logistics network that the country has ever seen.

The $121 million makes Dunzo one of the fattest startups in Bengaluru. Biswas insists that hasn’t changed anything. “My basic read in trying to build companies,” contends the young founder, “is that we shouldn"t take ourselves this seriously.” The idea behind starting the company, he lets on, has not changed even after six years. Dunzo wants to do what Uber does for people—press a button and a cab shows up. “Imagine I press a button and everything else shows up,” he says. “Everybody needs Dunzo.”

Back in April 2015, Sahil Kini, a venture capitalist, needed his cold milkshake on a sweaty Monday morning, and he didn’t know how to get it as soon as possible. Tom, his friend, had the answer. “*Why don"t you do this Dunzo thing,” he suggested. “It"s some new thing.” Kini’s blog in 2017 narrates the chain of events that led to his tryst with Biswas, and his first investment in Dunzo. A guy called Kabeer, Tom informed, has shared his WhatsApp number with a few folks, and does whatever one needs.

"Does what?” Kini asked. The reply left him dumbfounded: Kabeer moved a tree to Cubbon Park recently. “Just ping him with your milkshake request and see what happens,” Tom suggested. In 20 minutes, a scruffy bespectacled man stood beaming at the door, holding a milkshake bottle. “It was Kabeer Biswas,” recalls Kini, former principal at early-stage venture fund Aspada Investments.

Over the next few months, Kini Dunzo-ed everything. From polishing shoes and installing faux grass to a retractable awning in office, and repairing cracked iPhone screens, Kabeer did it all. “Want medicines at 3 am, buzz Dunzo. Forgot keys at home? Dunzo. 24 hours a day, 7 days a week,” he chronicles his absent-mindedness, and fixation with Dunzo, in the blog.

The result was on expected lines. Aspada Investments, along with Blume, seed-funded the venture. Dunzo got its first set of backers. What started as an idea, and that too on WhatsApp with three friends in Bengaluru, quickly exploded to 10,000 people in four months. “There were no full-time employees, no tech, nothing,” recalls Biswas, who spent days chatting and running around the city, trying to get stuff done for people.

The pace of growth galloped. Dunzo was fast becoming the talk of the town. Mumbai, though, was still waiting for its Dunzo moment. “My friends from Bengaluru asked me to ‘Do Dunzo,’ recalls Anil Joshi, founder of Unicorn India Ventures based out of the financial capital of India. Dunzo was fast getting the status of (let’s) Zoom during the pandemic: from noun to verb. It was solving a real problem by saving the time of the users and ‘will Dunzo’ was fast becoming a common phrase. “No wonder Google spotted them,” he says.

Back in 2017, Biswas didn’t spot, or anticipate, that he was running out of capital fast. The team expanded, the operations fanned out of Bengaluru, and expenses multiplied. Though Dunzo had hit the road, speed bumps were just around the corner. Out in the market to raise money, Biswas and his team drew a blank. “Everybody wondered how a delivery business could get more funds,” he says, adding that the startup has done its bit to get back in shape. It had cut its burn and become profitable in Bengaluru.

Nothing mattered, though. Over 90 VCs rejected Biswas in six months. “So that"s a rejection every alternate day, including weekends,” he laughs, rolling up his sleeves, fixing his glasses, and bursting into a brutally honest confession. His existing investors were running out of funds too. “Your business can consume our entire fund,” one of them quipped. “This is our last $300,000 that we can afford. Let"s see,” said the second VC. The writing was on the wall. Dunzo, and Biswas, badly needed a Santa Claus.

Enter Google in December 2017. The internet search giant reportedly led a $12-million funding round in Dunzo, making the startup the first venture in India to get direct funding from the US biggie. “If I would have told people 15 months back that our biggest investor would be Alphabet, nobody would have believed that,” recounts Biswas. “I don"t believe it even now,” he laughs. Over the next few years, Dunzo added more marquee investors.

The fund-raising spree though didn’t call for celebration. Biswas explains. “I have always wondered as to what is there to celebrate,” he asks. A company needs money to survive and grow. “We haven"t figured out how to do it by our own accruals. Hence the funding,” he explains. “The day you don"t need that money is the day you should be happy.”

Three years ago, in 2018, Biswas needed money again. Dunzo was about to exhaust its reserves. “It was a near-death experience,” he recalls. At some point of time, the startup just had seven-eight days of runway left. Biswas was staring at a closure. Luckily, another round of funding happened. A close tryst with death for the company brought about a humbling approach, and a realisation. “It makes you appreciate the fact that there is a factor of luck in building businesses,” says Biswas. It’s crucial to accept the variable. He explains why. There are a bunch of smart and intelligent people who have taken a stab at hyperlocal delivery in the past. Some of them had a very similar approach as well. But they didn’t survive. Since 2016, PepperTap, TinyOwl, Spoonjoy, Eatlo, Dazo and Opinio either shut shop or were acquired.

For Dunzo, a number of variables fell into place. Biswas lists out the top four. The timing was right consumer adoption happened at a faster clip, and it gathered pace during pandemic the startup got lucky with capital every time it needed it and it was fortunate to have the right set of talent. “If anybody thinks that they have a God syndrome in building startups, then it’s amazing,” he laughs. “I just want us to be thankful for the opportunity of being able to build something.”

The opportunity, and headroom for growth, for Dunzo is indeed massive. Rohan Agarwal, director at RedSeer, a consulting firm in the consumer internet space, points out the positives. The biggest is the massive boost to the digital economy during the pandemic year. “More consumption will increasingly get digitised,” says Agarwal. What this means is that India, with a vast network of unorganised retailers, will see small businesses moving more towards online. Hyperlocal models, he points out, have now enabled digitisation for such local retailers. The first set of players though, who entered the hyperlocal delivery market around 2014, got their timing wrong. “They were perhaps too early,” he says. Back then, the consumers were not mature, retailers were not ready, and the players were not capable of making the delivery operations work.

Another big positive for Dunzo, apart from the fact that it is the only vertical player left in the segment, is the reality that the big boys of ecommerce—Flipkart and Amazon—won’t be able to gate-crash the party. Agarwal explains. Building a hyperlocal business is quite different and complex than e-tailing models. “It needs significant time and investment even for the large players,” he says. The exit of well-funded players like Uber from food delivery makes it clear that hyperlocal business is not easy for even biggies.

The X-factor for Dunzo, though, is the tenacity of its investors to keep backing the venture and Biswas. “We shuttered not because of the flawed business model or hyper expansion,” says the cofounder of one of the heavily funded hyperlocal startups that wound up a few years ago. “Had investors stayed put, we would have survived,” he rues, requesting anonymity.

The X-factor, though, might turn out to be ‘Axe Factor’ if investors turn cagey in the future. “The day they turn jittery, Dunzo will find the going really tough,” the former entrepreneur adds.

Back in Bengaluru, Biswas is getting ready for another round of funding. Dunzo, which raised $40 million in a Series E round last month, is hungry for more. And Biswas is unapologetic. He will wait for six months, and then start preparing for another funding round. “We wouldn"t be raising money if we didn’t need the money,” he says, justifying the amount raised so far. The startup, he stresses, is in its growth stage, and might need a new set of people in the future that might be better placed than him. “In the future, if the company grows to be a lot bigger than what I"m capable of, I shouldn"t be the CEO,” he says. “Someone else should be,” he adds. “Main kuch aur karega. Operations karega, product karega, lekin stress nahin lega (I will do something else. I might look after operations or the product, but will not stress).” He surely won’t have to stress if more and more consumers keep Dunzoing their daily needs. The Dunzoing for capital can then begin to ebb.

Graphics by Sameer Pawar

First Published: Feb 11, 2021, 15:05

Subscribe Now