We met in March 2020, just off the successful launch of Bombay Sweet Shop, a disruptive, premium, modern take on Indian mithai, packaged with a focus on gifting. Tragically, that turned out to be Hunger Inc co-founder and celebrity chef Floyd Cardoz’s final interview—he died of Covid-19 later that month, leaving a legacy that his Hunger Inc teams still work each day to fulfil.

Later that year, Hunger Inc parted ways with another key member, then executive chef and partner, Thomas Zacharias, who went on to start up an initiative to platform regional ingredients through storytelling and events. He passed the baton on to chef Hussain Shahzad, who had originally worked under him at Hunger Inc’s first restaurant, The Bombay Canteen, and helmed its Goan-inspired sister, O Pedro.

Now, in addition to the original restaurants, The Bombay Canteen and O Pedro, Hunger Inc has in its portfolio the Bombay Sweet Shop, which has solidified into a full-fledged product business, with three physical outlets and deliveries available across the country. All of these establishments work on the core principle of wanting to platform Indian regional cuisine. But the next two ventures the group launched bore a slightly different purpose—to celebrate chef Floyd.

The first is the now-wildly popular sandwich deli, Veronica’s, launched in February 2023, famous for its pastrami sandwich and snaking queues outside. The second and newest Hunger Inc baby is a 12-seater chef’s table experience with Shahzad, which opened doors in February in an attic space above Veronica’s, called Papa’s. Papa’s, which opens reservations on the first of every month for its coveted 12 seats x four nights a week, is infamous for selling out in minutes.

“Both Veronica’s and Papa’s came out of wanting to celebrate chef Floyd—they were never part of some grand business plan," says Hunger Inc co-founder Sameer Seth. “The fact that we got [the 80-year-old space that housed] the iconic Jude Bakery the fact that it was just down the street from where Floyd grew up and where he would come as a child. And that we were able to convert an old bakery, reminiscent of his restaurant called Paowala, to a New York-style deli sandwich shop… it was poetic."

Papa’s, named after what the boys had nicknamed chef Floyd (‘Papaji’) came about to celebrate Cardoz’s other love—for fine dining, but the team decided to do it without the fuss.

“Fine dining at some point had become very solemn," says Shahzad. “It became a formula-driven approach to showcase your cuisine, and I didn’t want to be bound by that. Papa’s had to be personal, to tell the story of who I was, who we were, where Yash, Sameer and I come from, how Hunger Inc is evolving. And these stories had to be subtle—told through the taste, the experience, the story of evolution."

So Papa’s is a 10-course feast in a warm, well-lit space, with sing-along music, jokes along the way, magic tricks thrown in for good measure. It’s unserious in its approach to meticulously cooked and plated experimental, highly sophisticated dishes and cocktails, including one that serves up rabbit and ants and a clarified cocktail that holds marinara sauce and garlic—pizza in a glass, if you will.

“A conversation with [Papa’s general manager] Madhu sparked the idea for the elevated thayir sadam or curd rice—a dish he hated as a child, because he was forced to have it. He kept talking about how bland it was, so I took it up as a challenge," Shahzad says.

The thayir sadam gets more than an upgrade at Papa’s, with beetroot tartar and a garlic emulsion, along with a shiso tempura to replace the traditional papad crunch. It’s complex, umami-rich, flavourful and nostalgic, all in one bite, and even Madhu has to concede, Shahzad affirms.

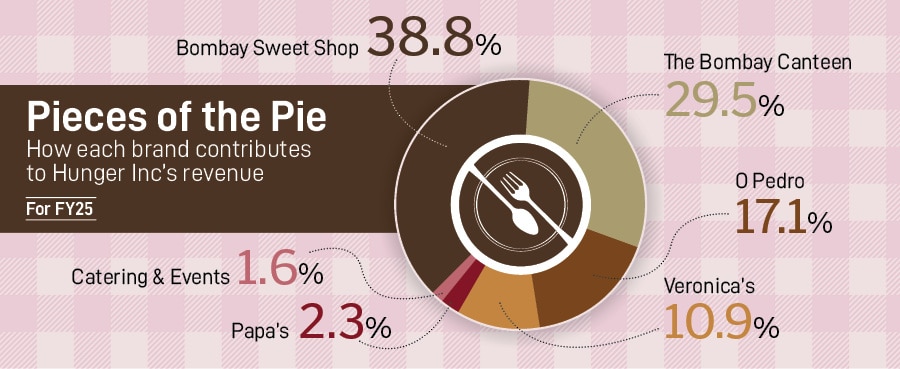

What must be tasting even better is that Hunger Inc’s revenue rose from Rs12.1 crore in FY21 to Rs57.8 crore in FY23 losses narrowed from Rs3.5 crore to Rs1.17 crore in this period. While their original star restaurant, The Bombay Canteen, still contributes to the bulk of the group’s revenue this quarter, the team expects Bombay Sweet Shop to take over.

Until last year, Bombay Sweet Shop had a revenue of about Rs31 crore. “This is up from Rs7 crore to Rs8 crore in the first year, although this was in the middle of Covid," says Yash Bhanage, Hunger Inc co-founder (and Seth’s Cornell University classmate). “This year, we’ll hopefully cross Rs50 crore, and that’s just with three physical stores in Bombay. If we are able to figure out the strategies on what another city needs, the right marketing strategies in Mumbai and the right distribution, and write that playbook down, then we have a framework to open in another city."

“When we do go elsewhere, we will have to do a certain regional diversification, but at least your framework of thinking, of store experiences, of engaging with delivery platforms will be solid, because by now we’ve been able to build trust with them," he adds.

![]()

How the chikki crumbles

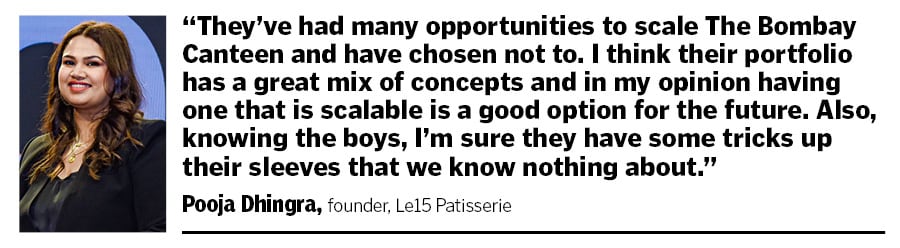

Of the four restaurants—The Bombay Canteen, O Pedro, Veronica’s and Papa’s—many have received offers to open shop in other locations. Seth and Bhanage have been reluctant and focussed on growing within the established spheres, so as not to dilute quality—perhaps guided by chef Cardoz’s own philosophy. “In terms of expansion, I never build something to expand it," the late chef told Forbes India back in 2020.

“I don’t think they ever intended to be a multi-outlet chain," says Vir Sanghvi, columnist, TV presenter and chairman, Culinary Culture, a food community that has started India’s own rating system. “They do one thing at a time, where they can control it, and that’s how they manage the quality of their food. People have offered to have them set up a Delhi Canteen, or an outlet elsewhere in Mumbai, but they’ve always refused."

The group’s scale draws largely from Bombay Sweet Shop, built to be a product business as opposed to a dine-in service. Bhanage and Seth say that, now, 70 percent of their time is invested in scaling Bombay Sweet Shop.

The genesis of the sweet shop has an interesting Forbes link. Bhanage, who was on the 2016 Forbes India 30 Under 30 list, travelled to the US for a Forbes Under 30 event, where he saw tennis legend Maria Sharapova talk about her confectionary brand, Sugarpova.

Sharapova comes from a humble upbringing in Russia, and recalls that when relatives brought her a Snickers bar from the US, it felt like a prized possession. When she and her father finally got a chance to visit the US for tennis, she imagined a candy store like Willy Wonka—but ended up at a drab grocery store instead.

![]()

“Ever since, she wanted to start a confectionary brand that would be aspirational, and that’s how Sugarpova came about," Bhanage recounts. “That was inspiring—in India, too, the aspirational sweets were the Ferrero Rochers and cupcakes and macarons, not Indian mithai. The starting point for us was to make mithai and mithai stores aspirational."

Another trigger was to build a brand that Indians could be proud of, one they would take as gifts from India when they travelled. The Bombay Sweet Shop menu, fashioned by chef Girish Nayak, now features traditional kesar paak and motichur laddoos, but also a cult favourite coffee-rasgulla-tiramisu and a take on an ‘inside out chikki’, in the form of butterscotch chocolate barks.

“I come from a restaurant background, where you make dessert for people to eat immediately, so it’s taken a shift in mindset," says Nayak. “The main challenges in a product business are to have consistency, and a longer shelf life. It’s taken us a lot of trial and error in terms of both recipe-testing as well as packaging. For instance, earlier we could only do 50 portions a day of the coffee rasgulla—now it’s close to 500."

The second part of the puzzle is to build trust. Automation helps with some processes, but a lot of the work still requires handcrafting. The barks, for instance, can use some machines to scale up quickly.

“It’s a product that helps us gain customer trust," Nayak says. “Next, they are likely to try a Bombay chikki, which is a sweet-savoury mix. Then when a festival rolls around, they say, okay, I’ll try the orange-biscuit flavoured modak, because I trust the brand to make good products. That’s what helps us innovate."

Bombay Sweet Shop wants to stay away from chemical preservatives to extend their product shelf lives, therefore rely on a data-driven approach to forecast an optimum number of items that will sell within the prescribed shelf life.

“It’s a business that needs to be analytical," says Bhanage. “We would keep believing that if someone tastes our product, they will fall in love—but how do you get them to taste? Anushka, who used to do data analytics for us, would keep pushing me to serve gulab jamun to whoever came into our Byculla store, but I wouldn’t. Then I checked with the delivery platforms about what the most searched items were—the first was obviously biryani, and the second was gulab jamun."

So, the team used the gulab jamun as a customer acquisition tool, priced competitively, not as premium as the rest of Bombay Sweet Shop. “We saw the numbers pick up, but not revenue, since it was priced lower. So, we went back to the delivery platforms and asked, what is the top-selling dessert in the city? The answer was tiramisu," he adds.

The Bombay Canteen had one of the city’s most iconic tiramisus at the time, featuring coffee-soaked rasgulla. “It was a prime product for us, and fit our fusion dessert category—but we needed to increase its shelf life to add it to the Bombay Sweet Shop menu," Bhanage says.

So, the recipe went through R&D, and eventually the team came up with a recipe that uses a bit of white chocolate and mascaporne together to create a shelf-stable product. As Nayak said, in six months, they managed to increase the production of the coffee rasgulla 10-fold.

Bombay Sweet Shop now has three physical restaurants in Mumbai—at Byculla, Bandra and Kala Ghoda—and 17 dark stores in Mumbai. “We’ve grown the business in an asset-light way, as digital allows us to, and the idea is that anywhere in Mumbai, you can have Bombay Sweet Shop mithai-namkeen delivered at home in 20 minutes," Seth says.

Even as the business scales, Sanghvi notes that Seth and Bhanage are restauranteurs at heart. “As successful as Bombay Sweet Shop is, and it is a model you can easily replicate, I think they enjoy people coming into the restaurant, sitting down to order… I don’t think any of their decisions have been entirely and purely business-driven," he says. “So even if it makes sense to close down everything and just have eight Bombay Sweet Shops, I think they will continue to do everything."

![]()

Keeping things fresh

In a cut-throat market like Mumbai, where restaurants open and shutter every other month, to create long-lasting F&B brands is a tall order. Hunger Inc is running up against the 10-year milestone coming up soon, and still hosts packed restaurants to its credit.

“I got to know Sameer and Yash before they opened The Bombay Canteen and what’s been constant is how they work with intention," says pastry chef Pooja Dhingra, founder of Le15 Patisserie. “They don’t do things because it’s trending or because it can make them a quick buck. They take their time identifying what they believe in, find the right product-market fit and then they do it with a lot of passion and a lot of heart. I think that’s why all their brands stand out in a crowded F&B space."

According to Bhanage, the key is simple—evolution.“I feel a lot of younger restaurateurs get this wrong—you open a restaurant in Year 1 with a point of view and a philosophy and that needs to evolve," he adds. “The key milestones for us at Hunger Inc have been that at various times we"ve been hit with various incidents that have shocked us, and we’ve evolved from there for the better but not lost our core philosophy."

So when The Bombay Canteen first opened, very quickly, chef Zacharias made it a blanket philosophy to only use indigenous ingredients. Now, chef Shahzad continues with that core philosophy, but seemingly foreign ingredients like avocados, for instance, do find their way on to the menu. “His logic is that if it’s growing on Indian soil, it’s Indian," says Seth. “And that’s fine."

![]()

The core philosophy, Shahzad says, is the play of form and flavour. “The idea is to give the audience a flavour that is familiar, in a format that is unfamiliar," says Shahzad. “A fun example is the O Pedro ceviche, made of red snapper. We’re serving raw fish, but in a broth with tamarind, ginger, garlic, cilantro, with crispy fried tempura bits on top. So, it gives you the idea of eating fried fish, but not really eating fried fish. This dish helped us define the North Star."

It’s this deep sense of research, and the respect for where the chefs and teams are from, which defines the group’s success, says producer and stylist Rhea Kapoor, a longtime patron of the restaurants. “At the same time, there’s a sense of adventure and joy, and a lot of respect for each element of a dish. If it’s a sandwich, the bread is respected as much as what’s inside it for a Kejriwal, the chutney must be just right, the egg is cooked perfectly. At each of their restaurants, their fundamentals are solid, and then they bring in a sense of fun."

The biggest evolution, Bhanage says, is that in the past few years, they’ve invested more on functional teams—human resources, accounts, finance and so on. Even so, their chefs are placed front and centre, and garner a lot of appreciation—especially Shahzad.

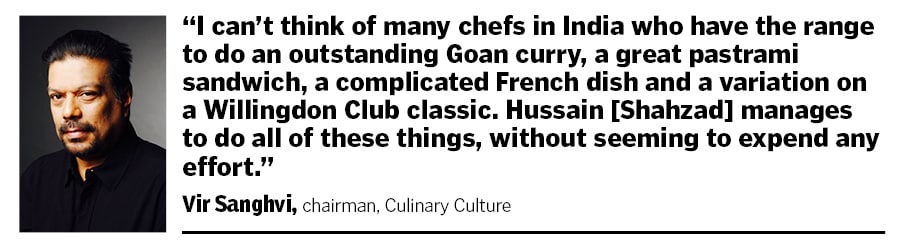

“I think it’s his range more than his commitment to excellence, which is, of course, outstanding," says Sanghvi, whose gourmet food initiative ranked Shahzad India’s top chef earlier this month. “I can’t think of many chefs in India who have the range to do an outstanding Goan curry, a great pastrami sandwich, a complicated French dish at Papa’s and a variation on a Willingdon Club classic, the Eggs Kejriwal. He manages to do all of these things, without seeming to expend any effort."

Even at The Bombay Canteen, which Sanghvi says he originally looked at as chef Floyd’s restaurant, the chefs’ stamps are now all over the menu.

“Even when they opened, you had Goan influences that came from Floyd’s childhood," he says. “But the Eggs Kejriwal, for example, became an elevated version of a club classic because of the chutney that Thomas [Zacharias] used—his mom’s Malayali recipe. Each chef has put his stamp on the food, and Hussain has done it more clearly than most, because he really knows how to get the flavours out of vegetables, out of meat. His food is full of flavour."