How PE firms are becoming bullish on startups in India

Private equity firms, which previously favoured safer IT and BPO companies in India, are increasingly willing to go after newer internet-based startups

Image: Shutterstock.com

Image: Shutterstock.com

When Aneesh Reddy, founder of Capillary Technologies in Bengaluru, was trying to raise money in 2015, there weren’t that many venture capital companies operating in India that could hand out cheques of $30 million to $50 million — the range Reddy was looking for, to buy out another company he was interested in.

“Most VC folks would dry up at $20 million or even $15 million, and PE firms started at $75 million,” he recalled in a recent interview with Forbes India. Reddy then became one of the rare Indian tech exceptions at the time, who successfully raised money from a private equity firm instead, at a stage when PE companies usually didn’t move in.

In fact, it was actually because New York’s Warburg Pincus came in with a “VC mindset” that he was able to raise the money from them at the time, Reddy recalls. He’s repaying the PE firm’s patience — as well as additional capital along the way — by turning his software company profitable and beginning to expand to the US. An IPO is not imminent, but is certainly an aspiration for the not too distant future.

“I think the ecosystem has changed significantly in the last five years,” Reddy says.

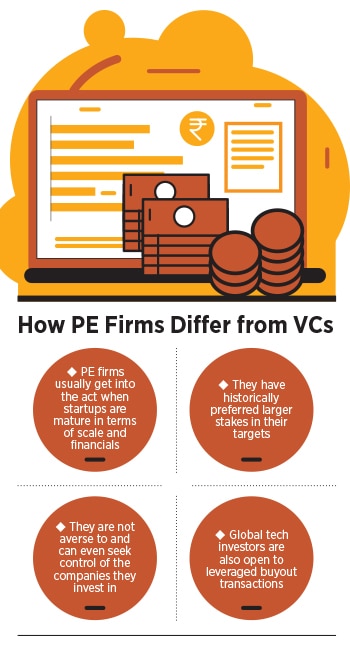

Today, PE firms are taking a much closer look at India’s startups, and investing earlier than they have been known to historically. From large, global names such as General Atlantic to smaller Indian PE firms such as Stakeboat Capital, there is growing appetite for opportunities in India’s tech and tech-enabled startup scene.

For example, in December 2020, Stakeboat helped bring in a larger Indian PE fund, Gaja Capital, to lead a $32 million investment into LeadSquared, a software company that helps businesses improve the outcomes of their sales efforts. Gaja, a 15-year-old PE firm, has also invested in XpressBees, a logistics and supply chain services provider, and Educational Initiatives, an edtech company.

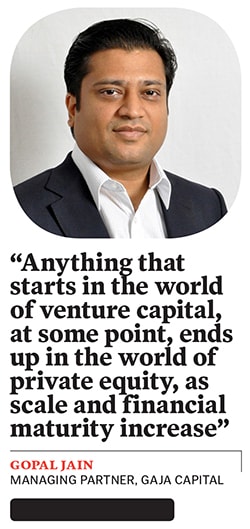

“Anything that starts in the world of venture capital at some point ends up in the world of private equity, as scale and financial maturity increase,” says Gopal Jain, managing partner at Gaja Capital. And that is happening at many Indian startups today. The Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the process, compressing about three years of change into one year, Jain says. The pandemic has forced startups to take a hard look at their businesses and ruthlessly prioritise, as a matter of sheer survival.

In specific sectors or segments, Indian startups have gained even global customers and can expect greater domestic consumption as well, he says. For example, Indian companies making cloud software or the software-as-a-service (SaaS) sector has gained about 5 percent share of the global market for such software. Over the next few years, Jain expects this to double. Further, a third of that will come from domestic demand as large established Indian enterprises shift more IT to the cloud and local growing startups consume more software.

LeadSquared is an example, with its software being used by customers including Byju’s, Acko, Amity University, OLX, Dunzo and Practo. Nilesh Patel, an IBM veteran, is a second-time founder with LeadSquared. He sold a previous startup he founded to US-based Symphony Teleca in 2010, worked there for a bit and then started LeadSquared. With the $32 million funding that Gaja Capital led, Patel is now ready to accelerate his push into the US market.

That more founders like Patel are emerging, with the combination of deep domain expertise and hard-earned experience of having already successfully built and sold previous startups, is another factor that makes it easier for PE firms to consider Indian startups today. The pedigree of the founders is so much higher today than 10 years ago that there is greater chance of them succeeding.

One of ways in which startups benefit by bringing in PE investments is that there is greater emphasis on getting the business to a point where it stops burning cash and starts making a profit on a sustainable basis, in a time-bound manner. “In the middle of 2019, when I said, ‘Look, I want to turn this profitable’, the kind of support we got from Warburg was insane, in the board,” Capillary’s founder Reddy recalls. And by early 2020, he got there. Further, the PE firm helped him keep the discipline through the tough times of Covid-19 and by the end of the year, remain cash flow positive.

VC companies emphasise a lot on growth, as they are often early stage investors. They also expect some of their investments to fail and bank on a small number of outsized returns. The experience with Warburg is that “they want every kid to make it,” Reddy says.

“There is a difference in thinking between the VC community versus the PE firms,” Patel says. In his case, the fact that LeadSquared didn’t get a big chunk of its revenues from the US was a negative, from the VC perspective. And then, it didn’t help that the startup was not in a field considered hot, but in the CRM (customer relationship management) space, where there were much larger companies competing.

The PE firms were more interested in taking a closer look at the fundamentals of LeadSquared and at how Patel had succeeded to build his business with low capital investment. They paid attention to the fact that LeadSquared was solving specific, important sales-related problems for its customers that others weren’t. Patel is also succeeding at solving multiple problems so that customers don’t have to worry about buying different software from different vendors and then face the headache of integrating them.

LeadSquared was the fourth investment that Stakeboat made from its first fund, which closed in 2019. “You might look at it as a CRM company, but they are probably a category leader in the sub-segment of lead management,” says Chandrasekar Kandasamy, managing partner at the PE firm, which led the $3 million Series-A investment into LeadSquared in 2019.

The willingness to look at fundamentals and economics, and pay less heed to whether a company is in a ‘hot’ space or not, can help PE firms spot winners even in sectors considered unfavourable. For example, Stakeboat invested in Sankalp Semiconductor, a specialist in analog and mixed signal semiconductor technology, in 2017.

While the overall semiconductor industry wasn’t one that VC or even PE firms were keen on at the time — the industry had seen ups and downs over two decades, and was largely led by multinationals — Stakeboat’s investment in the niche player paid off. Sankalp emerged as one of the largest companies in Asia in its specialised field of analog and mixed signal semiconductor technology and “within about 29 months, we sold the company to HCL Technologies”, Kandasamy recalls.

Over the next five years, he expects many credible candidates to emerge, with this combination of deep domain expertise and the ability to become category leaders in a specific segments that PE firms will find attractive.

Growing Interest from US PE Investors

India’s first generation of tech entrepreneurs, the founders of IT services companies such as Infosys and Wipro, chose to tap the public markets. PE deals in the sector were few and far between. One deal of note was at Patni Computer Systems, in which General Atlantic bought close to 18 percent in 2002 for $100 million and eventually exited in 2011 when US-based IT company iGate Corp and another large PE firm Apax Partners together took over Patni.

Deals in the IT services and IT-enabled services space remain a favourite of the PE companies, but especially over the last two years, they have started adding the newer startups to their portfolio.

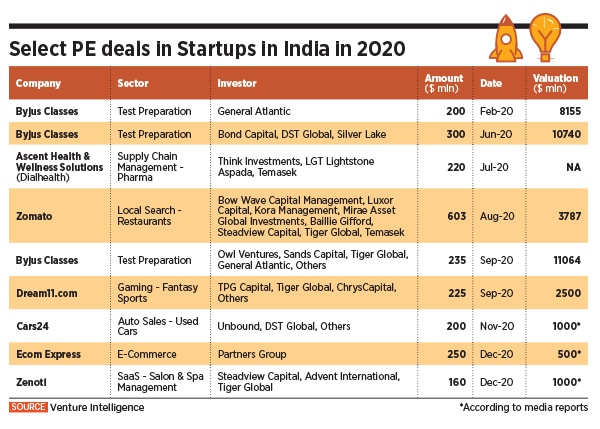

Over the last two years, General Atlantic has invested in Indian startups including Byju’s, Unacademy and NoBroker. Bond, co-founded by Mary Meeker who is famous for her annual reports on technology, DST Global, Israeli-Russian billionaire Yuri Milner’s investment firm, and Silver Lake, one of the world’s largest technology investment firms, invested $300 million in Byju’s in June 2020, according to research company Venture Intelligence. That is said to be part of a round that closed at $500 million, according to media reports in September last year.

The growing maturity of India’s startup ecosystem in parallel with the Reliance Jio Infocomm-led mobile internet revolution in the country is throwing up opportunities for the PE companies beyond the IT services and IT-enabled services companies. The trend was also catalysed by companies such as the SoftBank Group and Tiger Global, and large Chinese strategic investors including Alibaba Group and Tencent Holding, says Arun Natarajan, founder of research company Venture Intelligence.

SoftBank is now, however, “licking its wounds from the WeWork and Uber fiascos,” Natarajan says. “And the Chinese too have vacated the space” owing to a combination of India’s geopolitical tensions with China and China’s own crackdown on its tech multi-billionaires. At the same time, Reliance Industries garnered large investments from General Atlantic, Silver Lake and Vista Equity for its Jio Platforms unit. This will catalyse an increase in interest from the large US PE firms in Indian tech deals, Natarajan says.

“Internationally, these large PE firms have been tech-DNA, but have done non-tech and traditional deals in India,” Natarajan says. He expects that to change now. Indian startups looking at $100 million investment or more, will increasingly seek US investors, he says.

“We have become very interlinked with the US market all over again, and the US is a very tech-heavy market,” he says. “And to the extent that we become closer to the US ecosystem, we run both the risk and rewards.”

Investments are now happening in multiple sectors, from smaller deals that were more in the classic venture capital territory to late-stage venture funding that PE firms are jumping into. Earlier this month, CropIn, which offers machine learning based predictive analytics in agriculture, raised $20 million in an investment led by private equity company ABC World Asia. Zupee, a skill-based mobile gaming platform in India, raised $10 million in an investment led by WestCap Group a US-based growth equity firm.

Among the larger deals among startups in 2020, Indian fintech startup Razorpay raised $100 million in a round led by Singapore’s GIC and Sequoia Capital India, becoming a unicorn in the process Udaan, a business-to-business ecommerce company raised $280 million from existing and new investors, including Octahedron Capital, a US-based hedge fund and Britain’s Moonstone Capital and food delivery service Zomato raised $660 million from ten investors, according to Crunchbase.

In November 2020, there were 149 PE and mergers and acquisition deals in India, the highest number of such transactions in five years, according to accounting firm Grant Thornton. Of those, there were 77 PE deals with startups. These deals saw $723 million invested by PE companies in Indian startups.

PE companies are ramping up their involvement with India’s startups at a time when the economy is attempting to put the travails of the Covid-19 pandemic behind it. This could give the startup ecosystem the booster shot it needs.

(With additional inputs by Pooja Sarkar)

First Published: Jan 18, 2021, 14:55

Subscribe Now