How Snapdeal is turning around its fortune

After being on the verge of shutting down in 2017 following a failed merger with Flipkart, the Gurugram-headquartered company has seen revenue surge and unique customers grow by focusing on value ecom

Kunal Bahl, co-founder, Snapdeal

Kunal Bahl, co-founder, Snapdeal

Photo: Amit Verma[br]Kunal Bahl doesn’t like to give up easily. And certainly not without a fight.

A pioneer in the Indian ecommerce industry, Bahl co-founded Snapdeal—one of the country’s earliest unicorns—in 2010, when he was just 24. Within six years, it became the second-biggest ecommerce company in the country, with a market valuation of $6.5 billion. In that period, apart from becoming a darling among investors—Snapdeal boasted some heavyweights as investors, including Ratan Tata, eBay, SoftBank and Nexus Venture—the company also acquired 11 companies, the most notable being Freecharge and Unicommerce.

Then, in the summer of 2017, that dream run came crashing down. Seven years after it was founded, an imminent shutdown loomed over the Gurugram-headquartered company after a failed merger with Flipkart. It was left with inadequate funds, enough to barely last a month. Bahl and co-founder Rohit Bansal were in a similar situation sometime in 2013 when the funds had run dry, but 2017 was different. Raising money wasn’t going to be easy and it would only mean the end of the road, as Amazon and Flipkart tightened their grip in the Indian market. Even the planned sale to Flipkart was at a fraction of its peak valuation of $6.5 billion.

Bahl and Bansal, however, weren’t ready to leave without a fight. “With a perplexed team in the office and critics crowing from rooftops, it was much easier for Rohit and I to move away, washing our hands off a toxic situation,” Bahl wrote on LinkedIn in 2018. “That, however, was farthest from our minds.”

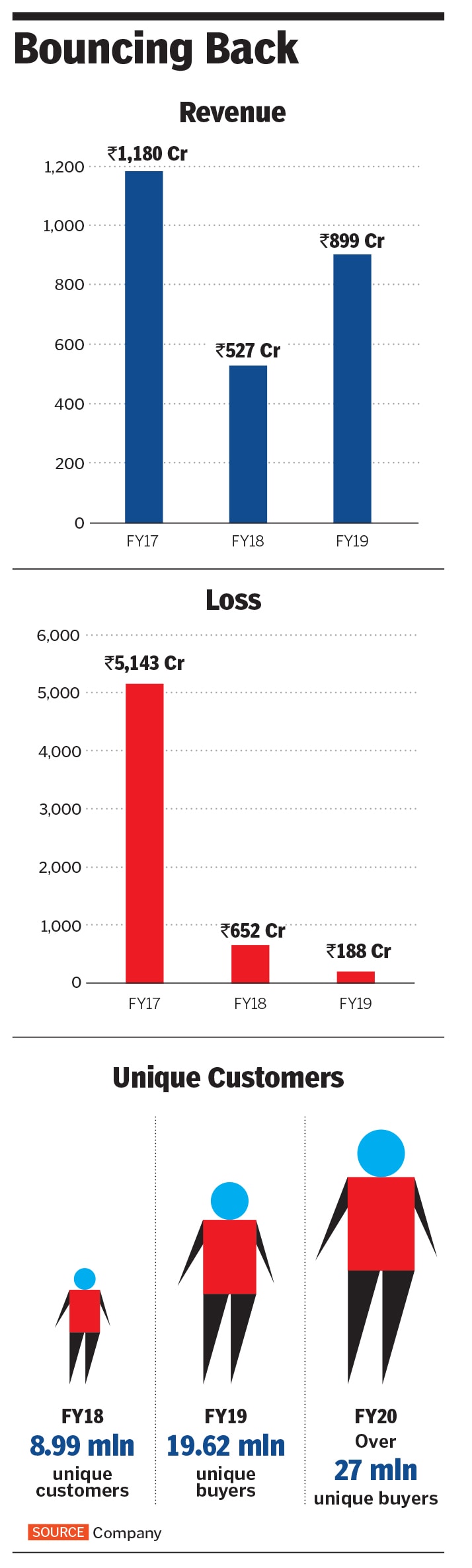

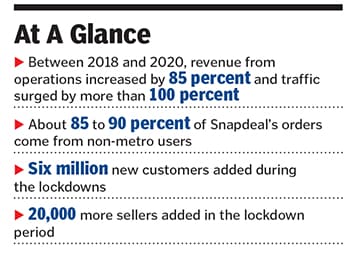

Now, three years later, perhaps as the last surviving entrepreneurs with the reins of their ecommerce business firmly in their hands, Bahl and Snapdeal are starting to script some serious turnaround. Over the last three years, Snapdeal has reduced its loss by an incredible 95 percent, while revenue from operations grew by 85 percent. Traffic, the company claims, has seen a 100 percent growth. Last year, more than 27 million unique buyers bought on the platform, and amidst the pandemic, it added another six million users and 20,000 new sellers, apart from its already-existing 500,000 sellers.

“We are the last large entrepreneurial Indian ecommerce company left,” Bahl tells Forbes India over Google Meet. “Outside of us are large global or Indian corporations. One has to wonder, why that can"t be just happenstance. It’s because we have been sharp about what we work on, and what we don’t want.”

“It’s about focusing on very few things and doing those few things very well,” Bahl says. “That’s a big learning for us as a company, as an entrepreneur, as a management team… that excellence comes with focus and doing very few things really well.” That focus on specialisation is what eventually brought Snapdeal to find a niche and shift its attention to what it calls value ecommerce. The segment, Bahl claims, provides a $163 billion opportunity in India and involves selling unbranded or lesser-known brands with very high value to the consumer, particularly in the low- and middle-income categories.

“It is about unlocking aspirations for those with less money,” Bahl says. “These customers are looking to make a discretionary purchase online but are fairly value sensitive. What they care more about is not for the big brand logo on what they are wearing, or what they are buying, but whether what they are buying is of value or not within a narrow price band.”

Piggybacking On Value Ecommerce

Bahl’s latest gamble towards betting on the value ecommerce category is largely a result of India’s growing mobile phone and internet penetration. India currently has some 504 million active internet users, of which about 70 percent are daily users, according to the Internet and Mobile Association of India. The country’s smartphone base is expected to swell to some 820 million by 2022, according to consultancy firm KPMG.

“With Jio entering in 2016 and the 4G penetration growing quite dramatically, it brought online hundreds of millions of new internet users who were earlier not online,” Bahl says. “A large number of them belonged to the low- to middle-income demographic in the small towns of India whereas earlier it was mostly consumers from the big cities who were affluent and buying online. Also, what we saw was that a lot of smaller regional manufacturers and traders started coming online in the last four years.”

That meant taking a step back and devising a different tactic to its earlier version. “Prior to 2016, mostly what would sell online and what would be bought online were brands,” Bahl says. “It’s not that the buyers don’t want to buy an iPhone or make some very expensive purchase. But they lack the ability to do so. However, they don’t lack any aspiration to look good or to feel good.”

To do that, Snapdeal began by building a portfolio of products that aren"t expensive or could potentially dissuade buyers. “We don’t do any discounting because most of our selection is incomparable,” Bahl says. “We have 200 million listings on our platforms. When comparability comes in, that’s when discounts become a critical element.” It also helped that the company found numerous manufacturers, who were looking to sell directly, unlike the traditional structure of selling through wholesalers and retailers.

“When we first started ecommerce, what was sold on ecommerce platforms was coming from traders. They were buying something from a brand and then re-selling it online,” Bahl says. “As internet and ecommerce proliferated in our country, the next generation of manufacturers in India, many of whom were entrepreneurs, began questioning the need for an intermediary and instead started selling online.”

India’s retail market is pegged to be around $785 billion, according to Technopak, of which some $220 billion is in the non-food retail category. Of this, Snapdeal believes that the non-branded retail space is around $163 billion, a market that it sees huge potential in, especially in bringing it online. “I believe we significantly dominate this segment, and more importantly, I feel in the larger scheme of things, ecommerce is still in its early days in India,” Bahl says. “When you look at the percentage penetration of retail that is online today, it is still in low single digits. People can argue whether it is two or three or four. It is still very modest.”But there has been a glimmer of hope, and Bahl’s plans got a much-needed boost as India announced a lockdown in late March, as the Covid-19 pandemic raged on. The lockdown meant a push towards ecommerce adoption, particularly for those who had remained sceptical about online purchases. Besides, the economic crisis that accompanied the lockdown, Bahl reckons, also made customers extremely wary about their purchases.

“People who were not buying on ecommerce started buying because they felt it was safer with more options online,” Bahl says. “The more interesting thing we see is that the pandemic has led to a lot of people in the more affluent and semi-affluent categories to reprioritise their needs and spend, where consumers are shifting towards value as a result of income uncertainty or economic uncertainty.”

And, as more buyers flocked online, sellers too saw a massive opportunity, helping create a wider assortment of value-priced products. “The moment sellers identified that people are shifting to buying online, what was earlier sold only in the bazaars was also being sold online,” Bahl says. “Some of the sellers who may have required a lot of convincing to try out ecommerce are now rushing and listing.”

Snapdeal claims to have added six million new buyers during the pandemic, in addition to over 1,500 new pin codes, taking its total coverage to over 27,000 pin codes. “Six million people is not a small number of new buyers,” Bahl says. “Sixty lakh people gravitating to a platform organically with 20,000 new sellers on board… we must be doing something right.”

The Comeback

The roots of that newfound success lie in the summer of 2017 when the merger with Flipkart was finally called off.

“This was a mergers and acquisitions process that had dragged on for more than half a year without an end in sight, with many discords outstanding, while at the same time, the business was losing money and cash reserves were depleting fast,” Bahl wrote in his LinkedIn post. “We were going to fall off a cliff if a call was not taken immediately to continue to build the business.”

That’s when Bahl and Bansal devised Snapdeal 2.0, with a focus on four key areas. It began with a hyper focus on the value ecommerce segment. “This market is three times larger than the size of the branded goods market—that had been the primary focus of the ecommerce industry till 2016-17,” Bahl says. “We seemed to understand this segment well because given our name, our origin as a couponing platform many years ago, it’s not that we were selling luxury before. It’s not very different from what we wanted to be and what we wanted to evolve into.” That also meant significant tradeoffs, including not selling the latest high-margin gadgets such as Apple phones or other premium stuff.

Today, about 70 percent of the company’s sales comes from apparels and home décor. The remaining is from electronics accessories or other items. “Being okay with saying no to things is the starting point of focusing as a company,” Bahl says. “It is tremendously hard when you have not been doing that for a long time. We got over the hump or potentially circumstances allowed us to get over that mental hump.”

Then, over the next few months, the company also began divesting or selling businesses that didn’t seem lucrative. The company had acquired 11 companies—it spent a staggering $400 million for Freecharge and others, including MartMobi, and Exclusively, in addition to investing in the defunct PepperTap. “We were a business that, over a period of time, felt non-core… it was important to build a strong core business, a flourishing marketplace, which had a strong market position,” Bahl says. Apart from getting additional revenue through its divestments—Snapdeal sold Freecharge to Axis Bank for some Rs385 crore—the company decided to cut down its operating costs significantly.

“You can build a Titanic or a speed boat,” Bahl says. “We were clear we wanted to build a speed boat. It moves fast and is easy to maintain… I am sure there are disadvantages like the mass, as you see from outside. But, given our management styles, personalities and past experiences, and most importantly, what we wanted to build—a platform company—we felt this was the right model, of having very lean operating cost in the business and operating costs that don"t grow linearly with our scale.”

In FY19, the company clocked revenues of Rs899 crore, with net loss shrinking to Rs188 crore from a staggering Rs5,143 crore in 2017. The company claims to have over 27 million unique buyers who purchased from the company in 2020, in comparison to a mere 8.99 million in 2018. Over the past few years, Snapdeal also managed to break-even in multiple months, claims Bahl.

Taking To The Fight

Despite its newfound focus, reclaiming lost territory won’t be easy. In 2015, Snapdeal held over 30 percent of the ecommerce market in India and had even set ambitions to take on Flipkart for the top spot.

However, since the near-death experience in 2017, and the eventual resurgence, India’s ecommerce industry has seen some serious transformation. For one, Mukesh Ambani, chairman of Reliance Industries [owner of Network 18, the publisher of Forbes India], has already launched JioMart, an ecommerce platform that has the potential to become the fastest-growing ecommerce platform in India, challenging Amazon India and Flipkart, according to Goldman Sachs.

Goldman Sachs reckons that Jio’s online gross merchandise value (GMV) will reach $35 billion by 2025, cornering 31 percent of the ecommerce market from around 1 percent now. GMV is the total value of merchandise sold over a given period. Besides, both Flipkart and Amazon are also pumping in enormous money to ramp up their business in India. In July, Flipkart raised an additional $1.2 billion equity from Walmart at a staggering valuation of $24.9 billion to take on the fight in the Indian market. Amazon’s Jeff Bezos had also promised to spend $1 billion on the Indian arm in early 2020.

Bahl, though, isn’t worried. “India is too big and too heterogeneous to be served by a single brand or company in any industry,” he says. “As long as you have a core that is strong enough, that creates a significant enough gravitational pull towards yourself of a large enough customer segment. That’s our goal.”

Last year, claims Bahl, over three crore unique customers came on Snapdeal, an indication of that gravitational pull, despite not indulging in aggressive marketing, something that has become a hallmark of the Indian ecommerce industry. “For every 100 people, three people bought once from Snapdeal last year,” he says. “If you aren’t differentiated enough, why would anyone buy, let alone 30 million people? Eventually, there will be 500 million buyers who will likely belong to this cohort (value ecommerce). Not the cohort of the affluent urban buyers.”

That’s probably why SoftBank, Snapdeal’s lead investor, is rooting for Bahl’s and Bansal’s vision. "Value is an enduring concept in India, as in most other parts of the world,” says Manoj Kohli, country head of SoftBank. “Snapdeal"s business model, which focuses on good quality products at a great value, serves the burgeoning, aspirational Indian middle-class market, which is huge in India. The enhanced propensity in the last eight months of people from smaller cities, towns and villages to shop online has bolstered this growth.”

SoftBank, which is among the largest shareholders in Snapdeal, hasn’t put any additional capital of late. “SoftBank has been on our board for six-plus years, and I would argue that their engagement on their board has gone up over the last two to three years,” Bahl says. “It has to do with the sharp positioning of the company, where investors tend to appreciate the fact that a company has a clear strategy—that instils confidence in investors.”

Experts, meanwhile, see merit in Snapdeal"s focus on the value ecommerce sector. "As an ecommerce retailer, you have to create an identity for yourself," says Devangshu Dutta, chief executive at retail consultancy firm Third Eyesight. "Because, for the customer, what matters is how distinct you are. You can"t be everything to everyone. Having clarity of your business helps significantly then."

PN Sudarshan, a partner at Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu India, reckons that the e-commerce industry by its nature tends to gravitate towards a limited group of companies that tend to dominate the segment. “Which is why, in most segments, there is a small group of large players," Sudarshan says. "Value e-commerce has a certain substance to it, because it offers a commercial platform for non-customised but unbranded categories of products as well as the generic brands catering to both the affluent and the aspirational markets.”

However, there could also be challenges. “There are critical matters of supply chain logistics, uniformity of quality standards and customer fulfilment in addition to regulatory and compliance issues that needs to be resolved for this proposition to realise its potential," adds Sudarshan. "These are best resolved through technology interventions, some of which may be readily available, but a significant set of solutions may need to be developed.”

What Next?

For now, Bahl is keeping his head low and focusing on capability creation. That includes investments into technology, including personalisation, algorithm and discovery.

“For most ecommerce platforms, intent-led search brings 85 percent of the traffic. In our case, 85 percent of the users discover products through browsing, and only 15 percent through search,” Bahl says. “It’s because we have invested a tremendous amount of effort into technology, data science and artificial intelligence to aid that discovery. In fact, we say please come to us when you don’t know what you want. We will help you discover something you want from us, which is a 180-degree turn versus traditional ecommerce companies which are all about, ‘We have everything, come search, and you get it’.”

Then there is a lean supply chain model in addition to focusing on zero inventory and being extremely asset-light. “We have also been keeping our operating costs very low,” Bahl says. “For instance, we served over 30 million customers or two percent of India’s population last year with just 650 to 700 people in the company and generated over $100 million of net revenue, which is our commission income. That’s no easy task.” That achievement, Bahl claims, means that on a per-employee basis, the company has generated revenue of the same magnitude as some of the top technology companies in Silicon Valley.

“As a company, we don’t think of the runway,” Bahl explains. “We make money on everything we sell post-marketing and fulfilment on a variable basis. Whatever little money we may be losing is because we are making some longer-term investment in capabilities.”

For now, Snapdeal has no plans to raise capital and if it does, it will be more of a choice than a compulsion. Still, he doesn’t rule out another fundraising. “We are comfortable. We haven’t raised capital for a few years,” Bahl says. “A lot of people would have said a few years ago that this company may not make it. But I think the proof of the pudding is that we haven’t raised external capital in the last few years, and we are still doing ok, which means that fundamentally we must have done something right with the business and the business model itself—it has pivoted the business from a cash-guzzling one to one that is capital efficient.”

Another round of fundraising, as and when it happens, will be largely to fund the company’s organic and inorganic growth. Over the last six months, Snapdeal claims to have had over 15 companies reach out to them to be acquired. “It’s a dynamic marketplace,” Bahl says. “We should not let our focus mutate into stubbornness. We have a flexible, need-based approach to capital, rather than just accumulate capital. It’s not the right use of the capital also.” That means Bahl is quite certain about not scaling up as quickly as Snapdeal had done in the past, flush with investor money.

So, where does Snapdeal go from here? “We believe the future belongs to companies that can focus, and while that may seem that they are relinquishing parts of the market along the way, it also means they will have higher certainty and probability of success in whatever they pursue,” Bahl says.

Clearly, Bahl has no intention of letting go. And he is only getting ready to tussle it out.

First Published: Nov 12, 2020, 14:48

Subscribe Now