Where is 10-minute grocery delivery headed?

After a frenzied 2021 for quick commerce startups, it might seem as though the bubble has popped with several companies shutting shop, sacking staff or being acquired. But some are still tackling the

It might seem as though the quick commerce bubble has popped. JioMart Express, Reliance Jio’s 90-minute grocery delivery service which it forayed into in March 2022, recently announced that it was ending the service. Ola Dash, Ola’s speedy delivery venture, folded in June 2022. While Dunzo, which saw Reliance acquire a 25.8 percent stake in January 2022, is said to be faltering, according to an industry insider. Tellingly, the Bengaluru-based startup has quietly been pushing for group deliveries rather than single deliveries to make the economics work.

Quick commerce startups—as they are known—offer customers about 2,000 groceries and everyday essentials that can be ordered via an app and arrive in 10 minutes. The goods are stocked in dark stores—mini warehouses strategically set up across cities—and delivered by a fleet of riders.

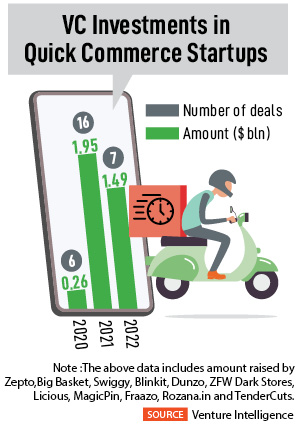

In 2021, quick commerce was one of the most-hyped sectors: It attracted $1.9 billion in funding from venture capitalists (VC), as per Venture Intelligence, a data provider. Startups hired hundreds of staff, set up scores of dark stores and pandered to customers, especially nervous ones who avoided supermarkets during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Zepto emerged as the poster boy of quick commerce, racing to a near-unicorn $900 million valuation in less than a year of founding in May 2022.

But by late-2022 the startups began faltering. Faced with huge losses, a funding drought and increased competition, they scaled back operations, fired staff and shut down dark stores.

But by late-2022 the startups began faltering. Faced with huge losses, a funding drought and increased competition, they scaled back operations, fired staff and shut down dark stores.

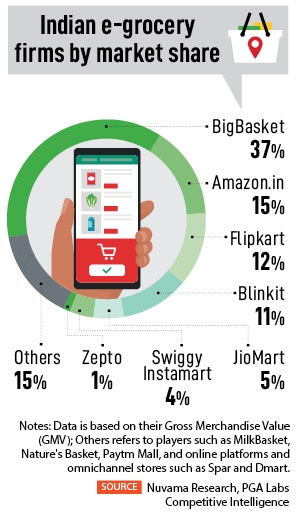

Come 2023, a handful of players are still fighting on. Zepto, still flush with cash from the funds it raised in 2021 and 2022, as well as the old guard of food delivery—Swiggy and Zomato, which run Instamart and Blinkit, respectively—aren’t rolling over any time soon. Neither is BBNow, Tata-owned BigBasket’s speedy delivery service. In fact, they believe demand for their services is only set to grow.

Redseer, a consultancy, predicted that the quick commerce market would boom from $300 million in early 2022 to $5.5 billion by 2025. Despite the macroeconomic slowdown, the quick commerce space will not be heavily impacted, says Rohan Agarwal, partner at Redseer. That’s because typically a purchase basket tends to be skewed towards essential, non-discretionary spends.

“Most of those who have folded their quick commerce operations did not make very meaningful efforts in the space. Only the serious operators ones are still into the quick commerce play," says Agarwal.

Unit economics are notoriously hard to crack in the quick commerce space.

“It’s all about driving better and better operating discipline," says Aadit Palicha, co-founder and CEO, Zepto. He dropped out of Stanford, along with his classmate and co-founder Kaivalya V, to set up Zepto in July 2021. The Mumbai-headquartered startup posted Rs142 crore in revenue on a loss on Rs390 crore in FY22. The company started up in July 2021, so FY21 revenues are negligible.

Dunzo, by comparison, posted Rs68 crore in revenue in FY22, up from Rs29 crore in FY21. However, losses widened to Rs464 crore in FY22, from Rs229 crore in FY21, according to Venture Intelligence. Dunzo declined to participate in this story.

Blinkit, meanwhile, made Rs301 crore in revenue in Q3FY23, up from Rs142 crore in Q2FY23. However, the numbers aren’t fully comparable as Zomato’s consolidation of Blinkit occurred in August 2022 which corresponds to a mere 50 days in Q2FY23. Swiggy doesn’t separately report its Instamart financials.

“Fundamentally, the unit of this business is the dark store," says Palicha. “Is your dark store generating cash? If it is, you can make the economics work." Currently, Zepto claims to have “hundreds" dark stores of which “dozens" are generating cash, he says, without letting in on absolutes.

Blinkit by comparison has 400 dark stores and plans to open 30 to 40 percent more in the next 12 months in “high potential neighbourhoods" in both existing and new cities, noted chief executive Albinder Dhindsa, in a letter to shareholders announcing Zomato’s Q3FY23 results.

Cash generated from dark stores goes towards covering fixed costs like rent as well as variable costs like delivery and fleet expenses. The quick commerce business is more skewed towards variable costs.

Says Agarwal, “To make money from a dark store, you need to be able to recover your fixed and variable expenses. That is where the element of density comes in." A dark store, for instance, cannot promise 10-to-15-minute deliveries if it is serving a large radius. So, the catchment that it serves needs to have enough density in terms of people valuing and willing to pay for speedy deliveries.

How then do you attract customers without handing out freebies and discounts?

Blinkit’s offering of diyas during Diwali helped it attract customers

Blinkit’s offering of diyas during Diwali helped it attract customers

Typically, dark stores stock anywhere between 1,500 and 2,000 SKUs (stock keeping units). A better assortment of products, beyond groceries and everyday essentials, helps attracts more customers to a platform. More customers mean more revenue. More revenue can be invested back in the business to achieve better product assortments. For example, Blinkit’s offering of diyas during Diwali helped it attract customers, noted Dhindsa during the analyst call at the time of the Q3FY23 results.

“The broader idea is to ensure that the customer does not go to the neighbourhood grocery/convenience store," says Swapnil Potdukhe, internet analyst at JM Financial Institutional Securities.

Within the product assortment, there are items that fetch higher margins than others. Fresh fruits and vegetables offer fatter margins of 18 to 40 percent, while standard FMCG products provide margins of 4 to 18 percent.

Within the product assortment, there are items that fetch higher margins than others. Fresh fruits and vegetables offer fatter margins of 18 to 40 percent, while standard FMCG products provide margins of 4 to 18 percent.

So, if a customer orders Rs1,000 worth of Saffola oil, for example, the quick commerce platform earns a commission of 3 to 4 percent. Whereas if a customer orders Rs300 worth of fruits where the margins are 35 to 38 percent, it earns much more. That means it’s not so much about average order values (AOV) as it is about the margin one earns off of them. Zepto claims to have an AOV of Rs400, Blinkit’s is Rs553, Swiggy Instamart’s is reportedly Rs400.

“Every dark store has its own nuances. It requires rigour and discipline across the supply chain. From the sourcing efficiency that we drive on the back end to optimising freight costs between, let"s say the back-end hubs to the front-end dark stores to driving IP and manpower productivity within the dark store itself to waste management and the depth of supply forecasting to knowing how much inventory you need per day per store—it’s a very granular business," says Palicha.

Dark stores typically take anywhere between 14 and 18 months to turn profitable. Zepto claims to take 14 months. Offline grocery players by comparison need 18 to 24 months for their stores to turn profitable. Zomato interestingly did not open any new dark stores in Q3FY23. “We only sign short-term leases till we have conviction on particular geographies," said Dhindsa during an analyst call.

Besides the usual levy of packaging charges and slapping on food delivery charges, startups have found a creative way to make money: Ad monetisation.

Blinkit claims to have partnered with 500 brands—both large and emerging—who find advertising on the platform to be a faster and more effective way to reach their target audience. Quick commerce players already have a captive audience. Brands can use their platform to build awareness, and also push sales through performance advertising. “Ours is a hyperlocal business where brands get visibility on the consumption trends at a neighbourhood level, for example, the kind of products people are searching for and ordering in a neighbourhood, by time of the day, and day of the week. That gives brands the ability to micro-target relevant audiences based on their brand positioning," says Dhindsa.

While startups don’t let in on the ad income, Potdukhe says they probably charge brands around 3 to 4 percent of gross order value (GOV). So, if a customer buys goods worth Rs100 in terms of GOV, expect ad income to be around Rs3 to 4.

“On paper, yes," says Potdukhe. But a number of factors needs to align for that to happen.

First, consolidation needs to occur. “The market isn’t big enough for everyone to be doing quick commerce," he says. Think of the food delivery space in 2015-16 when multiple players jostled for market share, prioritising growth over profit. Eventually most folded up or got snapped up, and the market settled to a duopoly with Swiggy and Zomato.

Consolidation will help companies achieve scale. That will help companies better optimise their costs and therefore unit economics.

Moreover, the spend on discounting and freebies in a bid to attract customers needs to go down. Attracting customers “who view quick delivery as a premium service and are therefore willing to pay for it" is key, says Redseer’s Agarwal.

“The model has its merits if you have the right strategy and proposition," he adds. Players, for example, might settle at delivering some items within 10 minutes, and others within 25 to 30 minutes. “That’s still quick delivery with a more measured approach. It’s about finding the right balance," he says.

Consider how Blinkit’s contribution margin (as a percentage of GOV) improved from -7.3 percent in Q2FY23 to -4.5 percent in Q3FY23. To be profitable, Potdukhe says, Blinkit’s number of orders per store per day needs to go from around 800-850 at present to 1,250-1,300, which will take another 1-1.5 years.

As Palicha says, “It’s an execution play, which requires extreme discipline." If rapid delivery apps can ace that, they’ll be able to deliver for customers and investors.

First Published: Mar 09, 2023, 16:17

Subscribe Now