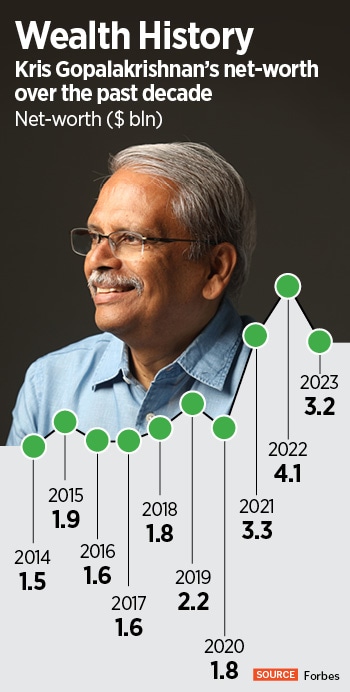

Since his retirement in 2014 from IT giant Infosys—which he co-founded in 1981 and where he held various positions including chief executive officer—Gopalakrishnan has walked the talk. Through his business incubator Axilor Ventures, he has invested in a slew of startups and venture funds, and his real-time net-worth as of May 30, according to Forbes, is $2.9 billion. At the same time, he has used some of this personal wealth for a cause.

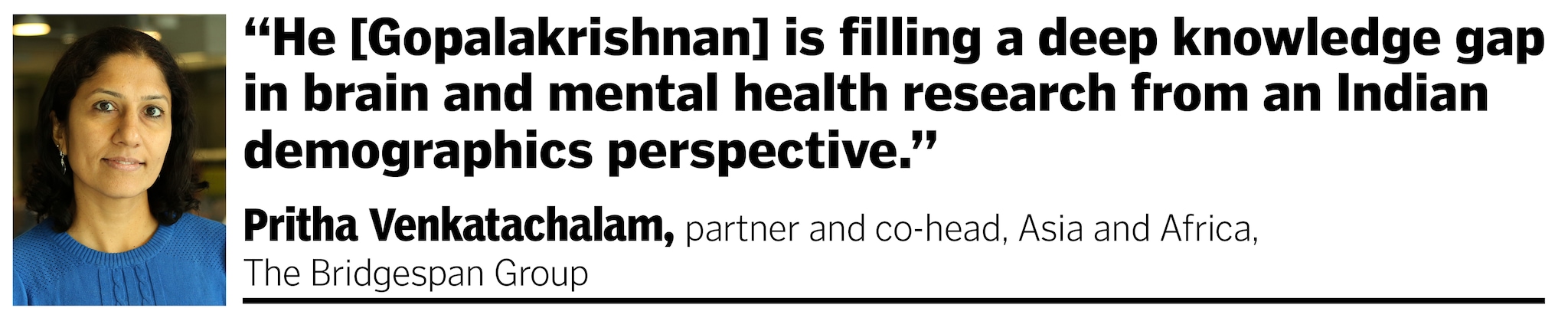

In 2014, Gopalakrishnan had announced a 10-year grant of Rs 225 crore to set up a Centre for Brain Research (CBR) inside the campus of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc) in Bengaluru. The 10-year grant period is in its penultimate year, and recently, Gopalakrishnan bolstered his commitment through an additional grant of Rs 450 crore over the next decade, becoming the biggest individual private donor at the IISc. He has made other grants towards scientific research, including at his alma mater IIT Madras, to the tune of nearly Rs 100 crore.

The idea behind the CBR is to specifically research neurodegenerative disorders like dementia, Parkinsons’s disease and other age-related cognitive decline. Gopalakrishnan, 68, wants to understand how the brain works, so that new treatments and interventions can improve the quality of life of older adults.

He also wants India to be the top five countries in the world when it comes to top quality research. “In the last eight years, India has become the third best location for startups. I’m hoping that pretty soon we will see significant progress on the research side and India will become one of the best locations to do research in the world," he says.

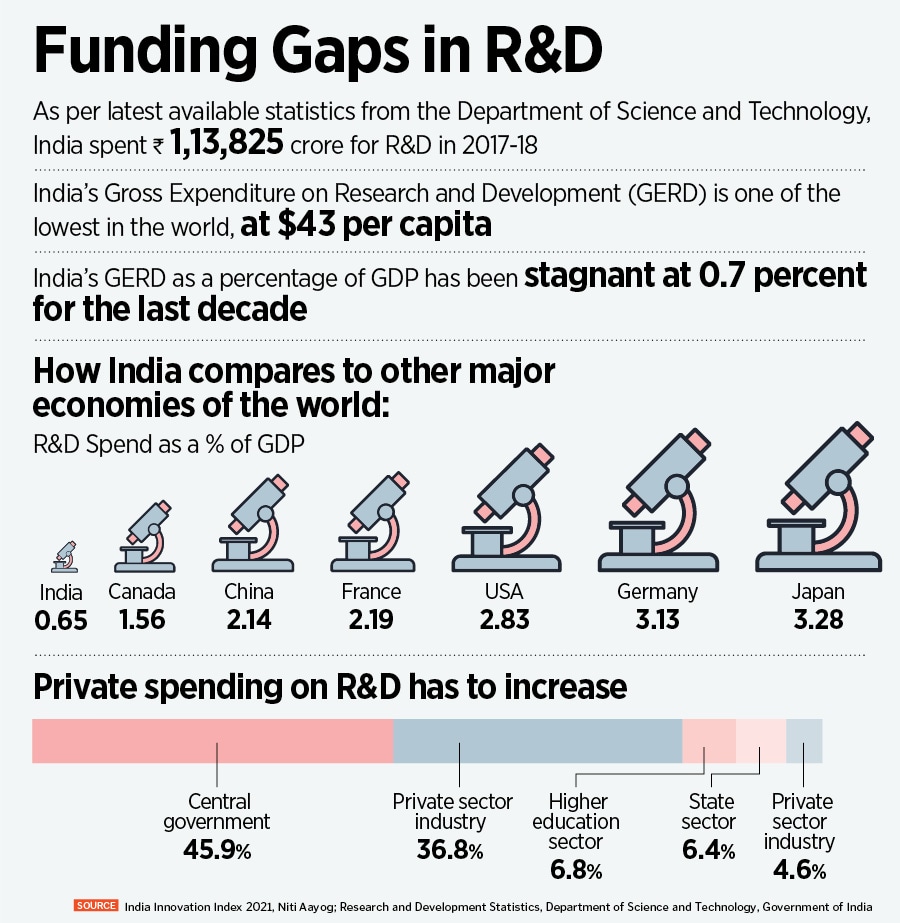

Research receives very little public and private funding in India (see box). If India has to achieve its goal of becoming a $5-trillion economy, the gross expenditure on R&D should be no less than 2 percent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), says the India Innovation Report 2021 by Niti Aayog. The country’s R&D investment, however, has remained stagnant at 0.7 percent for over a decade. “The share of private sources in this is even lower, at 0.2 or 0.3 percent of GDP," says Gopalakrishnan. “Somebody has to support research. But before I ask my colleagues, not just in the IT industry but across, to increase funding in research, I have to walk the talk, right?"

![]()

This is also one of his main motivations behind the recent, large second round of grants to the IISc, even before the tenure of the first grant was over. The CBR is undertaking a long-term, longitudinal study of neurodegenerative disorders, which can take decades. “So, we wanted to show commitment for the next 10 years as well, which would give confidence to the people who are working on the project. It also sends a message to other donors who might be interested in supporting, that there is continuity in the programme," says Gopalakrishnan, whose philanthropic contributions are executed through his non-profit Pratiksha Trust, which he runs with his spouse Sudha Gopalakrishnan.

Gopalakrishnan’s philanthropic focus is unique among his peers because of its focus on a relatively niche and underfunded area of social impact, says Pritha Venkatachalam, partner and co-head, Asia and Africa, The Bridgespan Group, which offers advisory and knowledge services to philanthropies, impact investors and non-profits. “He is filling a deep knowledge gap in brain and mental health research from an Indian demographics perspective, building a field over a tenure arc by working with partner organisations," she says.

Why is this important?

India’s population is growing, and also greying. As per the 2011 Census, people over 60 years of age form 8.6 percent of the population. The United Nations says that Indians in this age group will double by 2050, to almost 19.6 percent of the total population. Young adults below the age of 60 will continue to constitute a significant portion of the population over the next few decades, but this proportion will decrease as rate of growth becomes slower and the population ages.

In an ageing population, the burden of neurodegenerative diseases is likely to be high, says Yadati Narahari, director of the CBR, at IISc. He says that in India, as of 2022, there were already more than 6 million elderly individuals with severe neurodegenerative conditions and this number will likely increase to 15 million by 2050.

Narahari puts the projects undertaken by the CBR in this context. Neuroscience as a discipline is pursued only in a few places in India, he says, and not at the scale that you see in the US or Europe. “We want to undertake cutting-edge research and innovation that can help diagnose early, delay the onset, prevent, or effectively manage neurodegenerative disorders among elderly people," he says.

![]()

The flagship projects of the CBR are a 15-to-20-year population study of the aging brain in a rural cohort of 10,000 volunteers greater than or equal to 45 years, based in Srinivaspur taluk in Kolar, Karnataka, and an urban cohort of 1,000 volunteers in and around Bengaluru. Every year, every individual volunteer will undergo a number of assessments on various health indicators, including blood biochemistry and MRI. The idea is to see how the brain ages and what the changes are in an ageing brain over the years, depending on a person’s age, gender, lifestyle, food habits, location, environment and a variety of other conditions.

“This study will help us identify the pathogenesis [origination and development] of neurodegenerative conditions," Narahari says, adding that the studies have already been generating a large amount of data. For every volunteer, undergoing multimodal assessments each year costs upwards of Rs50,000. All expenses included, to conduct the two longitudinal studies, it costs about Rs 10-15 crore per year, Narahari says.

There is another study CBR is conducting with the National Institute for Mental Health and Neurosciences (Nimhans) on Parkinson’s disease, with about 500 patients. About 200 patients have been signed on as volunteers so far by Nimhans.

The CBR is also the nodal centre for the government-backed Genome India Project, involving 20 other institutes, which, as per an April report in The Hindu, is on track to sequence 10,000 Indian human genomes by year-end and create a database. This database will help create a reference genome for the Indian population, which means researchers can learn about genetic variants unique to Indian populations and groups, and customise drugs and therapies accordingly.

Another cutting-edge project Gopalakrishnan is funding at IIT Madras, which he says is the first of its kind in the world, is the cellular-level image mapping of the brain. His philanthropic association with IIT Madras started around 2014, when he set up three chairs in computational brain research with an endowment of Rs 10 crore each. The brain centre at the institute was inaugurated in March.

The centre at IIT Madras will leverage India’s strength in engineering, technology and computing to study the brain, says Mohanasankar Sivaprakasam, head of the Center for Computational Brain Research at IIT Madras. “Kris was very clear that he wanted to go after something ambitious. A high-risk, high-reward project that will put India on the global map," he says.

![]() The team took about 12 months to discuss and consult with national and international experts to come up with the plan. “The brain is largely unexplored, and the best whole-brain resolution you can get is from an MRI," he explains.

The team took about 12 months to discuss and consult with national and international experts to come up with the plan. “The brain is largely unexplored, and the best whole-brain resolution you can get is from an MRI," he explains.

The centre, therefore, is working to study post-mortem human brains at a microscopic, cellular level by slicing the brain into various thin sections, examining those sections, looking at how the brain is structured, analysing different human brains, studying how they develop, and high-resolution imaging and mapping of the brain.

A better understanding of the brain’s anatomy will allow researchers and scientists to find better drugs and interventions. “All this is going to lead to hundreds of petabytes of data, which we want to use to create digital maps of the human brain," Sivaprakasam says. “This kind of project requires a highly inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary approach. You’ll need to collaborate with people from medicine, engineering, technology, neuroscience etc."

The centre has collaborators with 25 international universities and institutes, and “seven of these collaborators have visiting professorships at IIT Madras," says Sivaprakasam, adding that as a backer, Gopalakrishnan has a keen sense of picking people who share his vision and passion. “He understands that people are key to achieving this," he says. “Equipment, infrastructure can be bought or created, but it is people who make high-risk science happen."

Defining His Philanthropic Vision

A philanthropic effort is, many a times, the result of personal experiences, which is why, about 15 years ago, Gopalakrishnan started with a cause that was close to him: Education. He believed that it was access to education that changed the lives of the Infosys co-founders, all of whom came from “middle-class or lower middle-class backgrounds," and therefore, he saw empowering underprivileged children with scholarships to pursue higher education as a way to give back. Even with the bigger focus on brain research today, he and Sudha Gopalakrishnan continue to support about 60 students per year.

When he left Infosys in 2014, he did not want to sit idle, and at the same time, did not want to pick philanthropic causes that competed with the social priorities of the IT services company. “I felt that with my experience and learnings, I can look at the value chain of education, innovation, entrepreneurship and research as the areas that I will support," he says. He does this by being on the boards of educational institutions, supporting research, funding startups and mentoring young founders.

![]()

When it comes to brain research, Gopalakrishnan knows he is in this for the long run, but he doesn’t mind because studying the brain is a personal passion. On one side, while he felt the need to be at the cutting-edge of creating new computational models to understand the brain, he also wanted to combine this with its societal implications to improve the lives of people. Other, smaller philanthropic contributions by Gopalakrishnan go towards supporting the livelihoods of farmers, through the Naandi Foundation and Centre for Collective Development. He has also funded and created Itihaasa, a digital app that chronicles the evolution of India"s IT industry.

Both Narahari and Sivaprakasam agree that the Infosys co-founder’s philanthropic contributions have attracted the confidence of other donors. For instance, the Brain Centre at IIT Madras now also counts Fortis Healthcare, SRL Diagnostics and Premji Invest as donors, while the CBR has other funders, including the Department of Biotechnology of Government of India, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Alzheimer’s Association, the SKAN Trust, SERB, and the Wellcome Trust. Gopalakrishnan remains the biggest donor for these projects in both institutions.

![]()

Gopalakrishnan is a man with a vision and has “high-level ideas about what the centre should expect to accomplish over the next 10 to 20 years", says Narahari. For instance, there are plans to go beyond scientific research to public policy as well.

Gopalakrishnan wants to make CBR a think-tank on neurodegenerative disorders that can help the government frame health policies. Narahari calls it bridging the “science society gap", where scientists no longer work in silos, and their work can help caregivers, patients and policymakers. “CBR is putting together a group of people, who, like ambassadors, will actively reach out to the elderly population, their families and caregivers to ensure they are well-informed about the latest discoveries in neurodegenerative disorders."

The brain research projects will have their share of challenges. Availability of volunteers or even skilled researchers and scientists, for instance. But Gopalakrishnan is always available to help, Sivaprakasam says, adding that it’s hard to find a philanthropic donor who is both passionate and compassionate, and has a deep knowledge of the space towards which they are contributing. Narahari says that Gopalakrishnan’s clarity of thought also comes with giving scientists a free hand to go about their work.

Venkatachalam says that measuring impact in health research has to come with a nuanced approach. “There’s risk, because research is a long-term process and doesn’t always succeed. There is a lot of trial and error here. But one way that we can look at results here from a philanthropic perspective is to define some shorter-term milestones and progress indicators that can help understand if you’re going in the right direction," she says. These shorter-term milestones, she explains, can be in the form of the number of peer-reviewed publications or partnerships with on-ground organisations or government adoption of a research output.

For his part, the Infosys co-founder looks at his philanthropy as patient risk capital, and does not want to set inflexible standards to measure impact. Giving back at scale becomes philanthropy, but giving back can happen at any stage in life, he says. “Even if you are 25 and don’t have money, you can volunteer your time. According to him, it’s all about trying to leverage whatever you have—money, networks or skills—for societal good. “It’s an obligation, and anybody who can, should give back," he says. “Giving has to be become a habit."

The team took about 12 months to discuss and consult with national and international experts to come up with the plan. “The brain is largely unexplored, and the best whole-brain resolution you can get is from an MRI," he explains.

The team took about 12 months to discuss and consult with national and international experts to come up with the plan. “The brain is largely unexplored, and the best whole-brain resolution you can get is from an MRI," he explains.