The changing contours of innovation in India

Home-based innovation in India has been oriented more towards the process dimension. Adoption of quality management practices paved way for incremental innovation. On the other hand, the main drivers

Image: Shutterstock[br]For a country of India’s size and aspirations, research and development (R&D) expenditure is fairly low. Unfortunately, it has also been static. R&D as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has remained between 0.8%- 0.9% for almost a decade. Let us step back for an overview of innovation in India- where it stands today, where the challenges are and what the future looks like. The observations presented here are based on my work with Shameen Prashantham at CEIBS in Shanghai and are related to a paper that we published recently in the Global Strategy Journal.1

Image: Shutterstock[br]For a country of India’s size and aspirations, research and development (R&D) expenditure is fairly low. Unfortunately, it has also been static. R&D as a percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has remained between 0.8%- 0.9% for almost a decade. Let us step back for an overview of innovation in India- where it stands today, where the challenges are and what the future looks like. The observations presented here are based on my work with Shameen Prashantham at CEIBS in Shanghai and are related to a paper that we published recently in the Global Strategy Journal.1

If you look at the evolution of innovation in India, what is also interesting is that there is a kind of duality. There are formal and informal streams of innovation systems that are running in parallel, and which need to meet more often. The first innovation system is the formal R&D-based, science-based innovation system which was given a huge push by the Government after independence as a part of India’s efforts to become part of the global science and technology community. It is the one we are most familiar with. But, the one which perhaps has had more impact on the country is the more home-based frugal, adaptive and ingenious innovation system. A good part of this is in the informal sector, but some of it resides in the formal sector as well. It has contributed a lot to health and well-being in India.

Parallel Innovation Systems

The major source of innovation in the formal R&D sector in India today has shifted to the R&D centres of Multinational Enterprises (MNEs). If you were to rewind about 20 or 25 years, you would have seen the biggest component of formal R&D was in the government sector, such as the labs of the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) etc. But today the most visible part or the locus is towards the MNE R&D centres. These centres in India largely support the innovation efforts of their parent companies – and they dominate the patent statistics. There has been some interplay with frugal approaches, in the sense that these MNE R&D centres have been influenced by them. They have at times expressed an interest in following frugal approaches but perhaps not to the extent that one would have expected.

The second set of innovators are Indian companies. The focus here is largely on industrial innovation, not so much about innovation outside the industrial sector. You will see that Indian companies have made sincere innovation efforts in some domains, particularly the pharmaceutical industry. But this endeavour has largely been within the technological frontier. Indian industry has been taking existing technologies and building on them in new ways. They have used several frugal approaches and adopted a range of technologies. A lot of it has been driven by the need to meet local needs of access and affordability, reflecting the kind of country we are.

There is another stream of this which has also been significant in the last two decades in areas like software and pharmaceuticals, where we have a thriving export-oriented industry. The recent phenomenon which is gaining more traction is the growth of start-ups. It is probably too early to say what direction the start-ups are taking as far as innovation is concerned. Some preliminary work suggests that they are largely adaptive and not really pushing the technology frontier. But it is perhaps premature to come to a judgment on that.

If one were to put all of this into some kind of a framework, you could say that innovation largely falls into two buckets. One is the dominant process side of it and the other is the product side which is largely dominated today by the MNE R&D centres in India.Most Indian companies focus inward and are driven by frugality. On the other hand, the multinationals are much more outward oriented, much more focused on knowledge and R&D. We have some Indian companies which could be described as Emerging Multinational Enterprises (EMNEs)- which are trying to now develop strong capabilities to make their presence felt in the international markets. Pharmaceuticals is the best example of an EMNE sector.

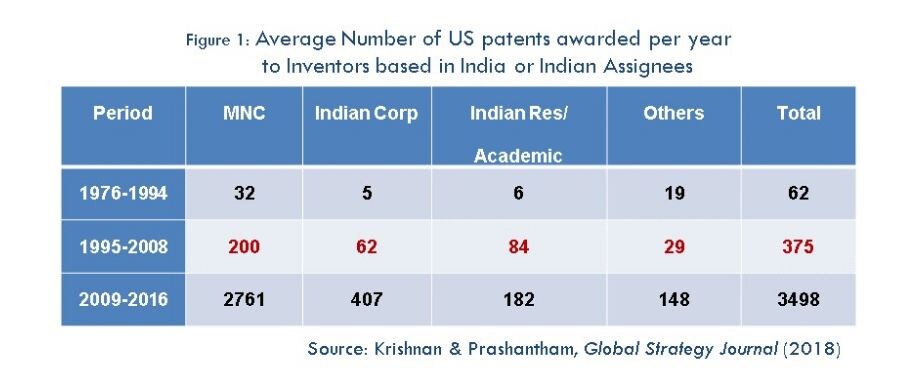

One interesting measure of how much intellectual property is being created by Indians in an international or global context is to look at the U.S. patents awarded to Indian inventors, i.e. when the first inventor listed on the patent is an Indian. One sees an overall huge increase in the number of patents awarded to Indian inventors since 1976 until the recent years. Why were these periods chosen? 1976- 1994 roughly represents the pre-liberalization period. 1995 to 2008 is the first rush post liberalization roughly until the financial crisis and 2009 onwards is the more recent phase.Equally breathtaking is the rise in patents granted to Indian inventors, dominated by multinationals– which essentially reflects the MNE R&D centres in India. Indian companies have been increasing the number of patents, but they are still far behind what the multinationals have achieved. While the Indian academic and research institutions had a fairly big jump in the 1995 to 2008 period, currently they are not growing at the same pace at which the multinationals are growing in terms of patents. Out of 3498 patents on an average per year being awarded by the U.S. patent office to Indian inventors, about 2761 are going to MNCs, around 407 to Indian corporates and about 180 to Indian research and academia.

Process Innovation

In parallel, there is this other angle to innovation- the frugal innovation ecosystem which has significantly impacted Indian prosperity in terms of Indian well-being, health etc. Aravind Eye Care is one such example. Also, Narayana Healthcare pioneered by Dr. Devi Shetty, started out by being able to do coronary bypass surgery for about US$ 2000. Today, they are pushing it to below US$ 1000. All of this is focused again not so much on cutting edge technology, but about finding out better processes so that you can really bring down the cost. It is an overwhelming focus on frugality which is driving such innovation.

Traditionally, innovation in India meant just producing efficiently. If you go back to the 1950s, we imported technology, so we needed to make it work. The emphasis then was about absorbing the technology and increasing efficiency. Products really came into the big picture much later, probably in the last 25 years. But the good news is that even within this product domain, Indian companies have been able to hold up their own in certain sectors.

Product Innovation

One good example for successful product innovation is the Indian transportation sector. One of the first sectors to be deregulated in India was the Light Commercial Vehicle (LCV) segment way back in the 1980s. It was thought that the entry of four Japanese companies through joint ventures was curtains for Tata Motors or Telco, as it used to be called at that time. But the surprise winner turned out to be a new LCV that Tata developed called the Tata 407. Even 30 years later today, Tata 407 is one of the dominant vehicles on the road. Its endurance has to do with it being rugged, easy to repair and good value for money. It is a product which is very well suited to Indian conditions and frugal in multiple aspects, particularly from the point of view of maintenance, upkeep, running etc.

In the last 25 years, firms in scale-intensive industries had to scale up and enhance technology to survive. For instance, take petrochemicals. Reliance is one of the largest companies today, but many other smaller companies simply folded up. Pharmaceuticals and transportation have emerged as the most locally R&D-intensive industries. The emergence of the service industry that we are all familiar with is an important phenomenon, and a lot of these service companies do innovation although it might not be at the technological frontier.

From an organisational perspective, how has this evolution happened? The main driver, at least for incremental innovation, was the adoption of quality management practices. Many people trace the origin of this to the entry of Suzuki into India, when Maruti Suzuki was formed in the early 1980s. It was Suzuki’s efforts which led to the spread of these practices in the automobile industry.

In recent years, we have seen some internal innovation process changes happening. We have seen efforts by large firms in innovation, looking at products or at least components. We have organisations like the Tata group where they have made very serious efforts to make innovation a part of the activity of every company within the group. When you consider breakthrough innovations, those are majorly driven by family-owned businesses where the owners themselves are strongly involved in the innovation process. We cannot imagine a Nano coming out of Tata Motors without Ratan Tata’s deep involvement nor could you imagine a Scorpio coming out of Mahindra without Anand Mahindra’s leadership.

Innovation in India

A lot of the MNE R&D in India is not visible in the end product because the entire product is not designed here. What Nirmalya Kumar and Phanish Puranam call “India Inside” tends to be the way a lot of MNE R&D is happening in India.2 The software that is written by these companies in India sits inside the product and it does not appear in the final product. But having started on the basis of cost arbitrage, today most MNE R&D centres in India have graduated to knowledge augmentation. They have started taking on lead roles- initially for legacy products, but later for new products for the developing and emerging markets.

However, there is one area where there is still some controversy. Has the multinational R&D system been a self-contained entity? To what extent have we seen genuine spill-overs to the rest of the ecosystem? One domain in which we have probably seen spill-overs is in the start-up domain. Increasingly, we find that a lot of tech start-ups are staffed by people who have come out of these MNE R&D centres. How these start-ups evolve is something that we will be watching very carefully as things go forward.

Speaking of start-ups- and this is certainly a very ripe area for research- India has done very well in terms of numbers. Several surveys say that India is number 3 or 4 in the world in terms of numbers.3 Much of it is driven by the government’s efforts, particularly through the Atal Innovation Mission and the Start-up policy. Industry associations such as NASSCOM and large companies like Google and Microsoft are also supporting the start-up ecosystem. However, how many of these start-ups are really R&D intensive is unclear. We do see some clusters around the Indian Institute of Science and around some of the IITs.

A small analysis done some time ago suggested that the top 9 start-ups in India in terms of revenues have just 30 patents between them.4 Most of the value that they are creating seems to be a result of adapting to global models, integrating the value chain with local suppliers and adapting to local needs, instead of doing cutting edge technological innovation.

The Indian innovation system has science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) capabilities, but most analysts agree that the quality is highly heterogeneous.

India has a national culture of creativity that goes back thousands of years. We tried to build a science and technology base post 1947 and we have some local innovative skills as well. The government support for R&D and innovation has historically been quite strong for the R&D in government labs and in public institutions. Now the government’s focus is largely shifting to start-ups and the industrial arena.

A challenge for Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) in India is that it has been highly focused on healthcare. The IPR system has certainly become stronger over time, at least as far as the legal framework is concerned but the quality of enforcement will again be an open question for some time to come. Venture capital has certainly become available in much larger magnitude starting from angel investors all the way up to longer term capital, private equity investors and so on.

There is a much more interesting international dimension now. Some of the largest so-called start-ups or at least largest young firms in India are today funded by international investors, many of them from China. Chinese and Japanese investors seem to be driving some of the merger activity in the start-up area and the impact that this is going to have on the evolution of the start-up ecosystem is something we need to see.

The Future of Indian Innovation

In recent times there have been a lot of start-ups in certain domains. E-commerce was the first flavour of the day, then came fintech. Now we hear more about artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML) and related fields. But, one question that remains open is the extent to which Indian start-ups will be able to pioneer new technologies and take them to the global stage so that they can actually become global leaders in their respective domains.

India does not have a very great history of riding new technology waves. We largely missed the semi-conductor wave. We have been followers in nanotech. In biotech, we have done a tad better but, in the past, we struggled to keep up with the latest technology. Is it going to be different this time, particularly with the new start-up ecosystem which will determine to a large degree what the future of innovation in India will be?

For instance, India has the largest base of mobile subscribers in the world.5 There are about 1.3 billion mobile connections, but we still do not have a strong manufacturing base of telecom equipment in India. We do not have an equivalent of Huawei or a ZTE, which is quite unfortunate considering the huge market which is already there in India. Can India develop technology capabilities related to its needs is the big question.

The good news is that there are a few companies that have developed strong technological competence. The MNE R&D centres which are a major locus for science-based innovation in India today are very rapidly embracing new technologies. Because of technological disruptions like AI and ML, many companies are looking to their Indian R&D centres to pioneer some of these activities. It is here in India that these companies have the largest strength of IT-trained professionals with competence in software. If they succeed in delivering, it would mean that the next generation of Indian professionals will be at the frontier of these technologies.

Edited by Ram Mohan Chitta

First Published: Jan 10, 2020, 15:44

Subscribe Now