Flipkart's PhonePe calculations

The fintech revolution in India is finally happening, and into the mix has entered India's biggest internet-era entrepreneurial venture, Flipkart, with its PhonePe unit. Kirana stores and consumers ac

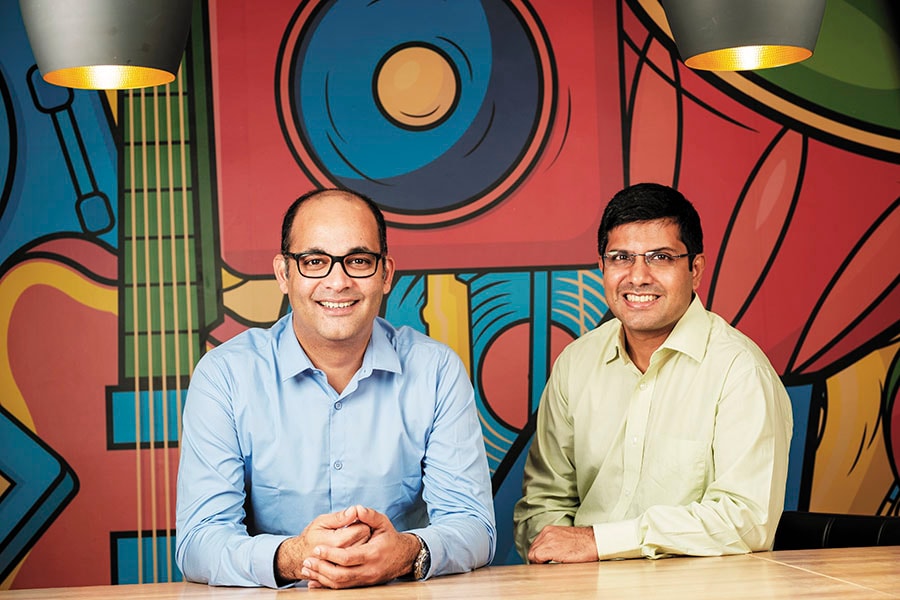

Flipkart took over PhonePe in April 2016 from its enterprising co-founders Sameer Nigam (left) and Rahul Chari

Flipkart took over PhonePe in April 2016 from its enterprising co-founders Sameer Nigam (left) and Rahul Chari

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes IndiaUPI transactions: October 2016—0.1 million, October 2017—76.96 million. What a story!” wrote Nandan Nilekani, former chairman of the Unique Identification Authority of India (UIDAI), in a tweet on November 1. Nilekani was, of course, referring to the spectacular success of India’s Unified Payments Interface, popularly called UPI, which every major payments provider—from banks to new-age mobile wallet providers—has enabled.

Riding this post-demonetisation (remember November 8, 2016?) wave are the mushrooming payments solutions providers, the biggest of which is the Vijay Shekhar Sharma-run Paytm, which supports the UPI platform, and the Bhim (Bharat Interface for Money) app, owned by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI).

Added to the mix is Flipkart’s latest attempt at the digital payments business: PhonePe, which it took over in April 2016 from its enterprising co-founders Sameer Nigam, 40, and Rahul Chari, 40, who continue to operate as CEO and CTO respectively.

They, in fact, are driving PhonePe’s latest gambit—a calculator-based point-of-sale (POS) device—to counter the challenges of this highly competitive, albeit fast-growing space, and also, to further the cause of digitising India. Nigam believes the device, launched on October 31, will “easily be India’s point-of-sale device of the future”. The duo started work on it about 18 months ago, and every single aspect of it has been developed in-house, designed and manufactured for India, they say.

The inspiration for it came in early 2016 when, while walking around markets in various cities and towns, the complexity of India’s market became apparent to Nigam and Chari. And, therefore, the need for simplification.

The organised part of the retail sector is still small in India, while various estimates peg the number of mom-and-pop stores—or your friendly local kiranas—at between 50 million and 60 million. For them, most solutions available today don’t solve basic problems, Nigam says. The PhonePe device is targeted at these merchants it is durable and affordable, and something that they can understand intuitively, adds Nigam. He also feels that it has to be a device sans too much text. Something with a “lot of English” in it would discourage small merchants from using it. The same holds true for overloading the device with tech—it would make it intimidating for the consumer and the merchant alike. In fact, these are some of the reasons why existing machines—largely foreign technology plonked into India, and therefore working only at shops large enough to use them—haven’t really penetrated beyond the big cities and towns, and even then, these typically accept only cards. PhonePe’s calculator-based POS device is targeted at merchants in India’s kirana stores. The company says the device is durable, affordable and something they can understand intuitively

PhonePe’s calculator-based POS device is targeted at merchants in India’s kirana stores. The company says the device is durable, affordable and something they can understand intuitively

Image: Vivek Prakash / Reuters

That’s also why India, a country of 1.3 billion people with only about 20-22 million credit card users, has seen so many people download and use apps such as Bhim to make UPI-based payments.

UPI rides on a backbone created by the government-backed NPCI, with most big banks as stakeholders. Users get to link a bank account with a virtual private address, send each other money and make payments, eliminating the need to share bank account details.

The number of POS devices was even more telling, Nigam recalls: “When demonetisation happened, there were only about one million devices in use in the country,” he says, citing government data. He was referring to India banning its two highest-denomination currencies in November 2016, in a move to unearth and curtail black money. Economists and pundits continue to debate the consequences of the move, but it certainly pushed many merchants towards adopting digital payments. Many of India’s internet- age fintech startups reported a surge in the adoption of their various solutions, and the corresponding volumes of transactions in the months that followed. Demonetisation probably also boosted UPI-based transactions, ergo Nilekani’s tweet.

With this environment as the backdrop, PhonePe’s vision of reaching the millions of kirana stores doesn’t seem farfetched. Especially given that they have kept it simple: It “looks, and feels and acts exactly like a calculator,” Nigam says. It has three more buttons in purple and those are the ones for the electronic payments. It costs less than $10 (about ₹650) to make, it doesn’t require any data on the merchant’s side. It works for months together on standard double-A batteries, and works as a plug-and-play device. Also, PhonePe is giving it free to the merchants, at least in its pilot run of 5,000 units, starting in Bengaluru.

The device may also be the button that triggers Flipkart’s thus-far unfulfilled digital payments ambitions. At any rate, Nigam and Chari seem to be the appropriate duo to back for the homegrown ecommerce major.

Nigam and Chari go back a long way, over two decades, and PhonePe is, in fact, the third company that the duo are building together. Their academic tracks ran in tandem: They studied engineering together at Sardar Patel College of Engineering, University of Mumbai, getting their degrees in 1999 then they both went to the US to pursue their masters degrees in computer science—Chari at Purdue University in Indiana and Nigam at University of Arizona.

Chari moved back to India in the summer of 2008 from Cisco Systems, where he’d been working, to set up one of their product lines in India. He wanted to break into the consumer internet space, but his nine years as an embedded software professional—including a stint at Andiamo Systems, a data storage specialist—didn’t exactly equip him for that at the time, he recalls. The only option was to do something on his own, he says, and jokes that “if Google or someone had offered me a job, then probably this [running PhonePe] wouldn’t have happened”. People wait to deposit scrapped ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes in Mohali. Demonetisation pushed many merchants towards adopting digital payments

People wait to deposit scrapped ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes in Mohali. Demonetisation pushed many merchants towards adopting digital payments

Image: Anil Dayal / Hindustan Times via Getty Images

Meanwhile, Nigam was just adding to his qualifications an MBA from Wharton, where he won a small grant, about $15,000, from a contest for business proposals, which “gave me play money,” he recalls. This was also in 2008-2009.

A chance meeting at a common friend’s wedding, in Mumbai, got them started off on their first venture, Manoramic, for which Chari ditched a real estate startup he was attempting. They bootstrapped Manoramic, switched to become a business-to-business company and actually ended up becoming quite successful.

This avatar of Manoramic, they called it Mime360, short for Manoramic International Media Exchange, and it became the platform to power Gaana’s launch, streaming music for Saregama India, Universal and other biggies in the music industry. And, on top of that, the two entrepreneurs even built a lot of analytics, so, for instance, “we could tell Saregama that ‘Chura Liya Hai Tumne’ was their most played song, ever,” Chari recalls. They could even tell which site has played the song, exactly how many times and at which IP address, giving Saregama the chance to attempt differential pricing. This was in 2009 and 2010.

Around August 2011, Flipkart, which was looking to get into content, was pointed to Mime360 by the music industry, and “it was a meeting of minds,” Chari recalls. A meeting on a Friday between Chari and the then Flipkart Head of Engineering Mekin Maheshwari and co-founder Binny Bansal was followed up with another a couple of days down the line and “we folded up the following Monday,” says Nigam.

Thus was born Flipkart’s Flyte online music download store, built by Nigam, Chari and their 10-odd staff, who had all moved from Mumbai to Bengaluru lock, stock and barrel. “Not much stock, lots of lock and barrel,” Nigam jokes about the all-stock deal for Flipkart to acquire Mime360. Unlike existing POS machines—largely foreign tech plonked into India—PhonePe’s calculator-based device will “easily be India’s point-of-sale device of the future”, believe its founders

Unlike existing POS machines—largely foreign tech plonked into India—PhonePe’s calculator-based device will “easily be India’s point-of-sale device of the future”, believe its founders

Image: Nishant Ratnakar for Forbes India

Flyte had a short flight, launched in 2012, and killed in 2014. The reason, they say, wasn’t that there wasn’t a demand for music downloads. Neither do they blame piracy. “I genuinely believe that piracy isn’t the reason we shut down it was micro transactions,” Chari recalls. “We had songs at three-rupees-a-pop, and you could download at 320 kbps,” he says. “And iTunes was only 192 kbps at the time,” Nigam adds.

“It was just the friction to actually pay for something that is ₹3, which is an impulse purchase. That whole impulse gets deflated in the face of the kind of payment experience that was there back in 2012,” Chari says. “That still hurts.”

But the compulsive entrepreneurs that they are, they took that hurt, and turned it into the motivation for building something that would obliterate the problem that killed Flyte: The absence of a simple, fail-proof, online micro-payments mechanism. Nigam and Chari, who quit Flipkart soon after Flyte’s demise, built PhonePe in the latter half of 2014 and 2015, and sold it right back to the ecommerce company barely 18 months after starting the venture, in an all-stock deal.

Now, that micropayments solution is evolving at PhonePe, and Flipkart has once again become the “vehicle” to distribute it at scale and take it to greater heights. The duo recently bagged $500 million in funding commitment from the parent company—an indication of both the fintech opportunity in India and Flipkart’s determination to not be left out of the game by the likes of Paytm.

Happily, their intention is backed by a clearly differentiated product. Unlike other new solutions in India like QR codes, which one scans with a relevant app and enters the amount to pay, it will be the merchant who gets to enter the amount to be charged on the PhonePe device—similar to the machines used to swipe credit or debit cards. Therefore, the merchant doesn’t need to verify if the customer has entered the right amount. “There is [also] a lot of mistrust of the new tech among early adopters of digital payments as to whether the money is coming in,” Nigam feels.

The machine has built-in simple “trust markers” by way of LEDs that light up to show the status of a transaction—blue for an ongoing one, green for a successfully completed one and red if a payment fails. As simple as that. The money goes directly into the merchant’s bank account, Nigam points out. This doesn’t involve a wallet and related withdrawal fees.

undefinedPhonePe has checks to ensure money is not lost in a failed transaction[/bq]

For the customer, PhonePe acts as a “payments container”, Chari says, meaning it can store multiple payments options like third-party wallets, credit and debit cards. Jio Money is the first wallet that PhonePe has integrated, and the founders expect to add all the other most commonly used options, from cards to UPI-based methods. What this means is that the consumer has the choice of the payment option of her preference.

It helps that the merchant doesn’t even require a data connection. The payment, in fact, relies on the data connection of the consumer’s smartphone, which is getting better and better in India as 4G rollouts pick up.

In practice, the exchange between the smartphone and the device happens using Bluetooth, therefore the payment is contactless, requiring one to just hold the phone close to the device for a few seconds. “What we have solved… is the consumer and merchant have to exchange no information… we have basically emulated a cash transaction,” Chari says.

Of course, all the clever stuff happens in the backend. PhonePe does the grunt work required to ensure a Know-Your-Customer as regulated by the Reserve Bank of India, and assigns an ID to a merchant. It is only that information that is hardwired into the device given to that merchant, and when a consumer’s PhonePe app captures that ID, everything else falls into place—money is debited from the payer’s bank account or wallet or card as the case may be, and sent directly to the merchant’s bank account.

On the device and PhonePe smartphone app too, there are processes built in to ensure that neither party loses money in a failed transaction, says Device Engineer Ankit Daftery, who led the project to build the POS device. If for some reason the Bluetooth connectivity fails in the middle of a transaction, the payment is cancelled “bi-directionally,” Daftery says. In the event a consumer sees her app showing a successful payment, but the device’s LED is not showing green, there is a “verify” option built into the PhonePe app, he adds.

The reconciliation of the day’s transactions will be available to the merchants via an app as well.

For the time being, consumers do need to have downloaded and installed the PhonePe app on their smartphones, but “that is only Version 1, and we will soon be opening up the SDK [software development kit],” Chari says.

In other words, the software development kit for the device will soon be openly available to all developers and the device itself will work with other apps and payment options. For instance, in the near future, one could use a Paytm or MobiKwik app on one’s smartphone and make a payment on the device.

Such “inter-operability is really the only way forward,” Chari says. “Besides, on the consumer side, we will all be competing with each other anyway [to acquire and retain more users],” Nigam points out, “whether a payment method is open or not”.They claim 50 million instals of the PhonePe app, and the Google Play app store shows the number of instals as between 10 million and 50 million as this story goes to print.

And they now hope to see their POS machines in the hands of hundreds of millions of sellers across the country—from a push cart vegetable vendor to mom-and-pop kirana stores to any shop that wants to include the option.

The duo run PhonePe, with its 200 staffers, from within Flipkart now, mostly out of an office building that is next door to the one that the parent had long grown too big for, in Bengaluru’s Koramangala area—home to many a startup.

Some of PhonePe’s conference rooms, such as the one which celebrates Michael Jackson, with a wall hanging that has what reads like a Wikipedia entry on the late pop music genius, have a nice view of a park and several trees—an increasing rarity in Bengaluru—outside the window.

Like in Flipkart, different floors have different themes, and Nigam and Chari have picked the room in the music-themed floor for their meeting with Forbes India. “Maybe it reminds us of what we loved to do,” quips Nigam.

The confidence is palpable. After all, this time, Nigam and Chari are entering the scene at an opportune moment. Their timing is far more on the dot when it comes to digital money in India, than when they launched Flyte. A host of factors are coming together to bring the country to the brink of a digital “revolution”, says a Boston Consulting Group (BCG) report. “India is set to leapfrog many advanced economies,” it adds, as the “new Indian consumer” is digitally savvy and expects to transact in a mobile-first world. In three years, BCG projects, some 120 million Indians will access at least one digital channel in researching a financial product purchase, and the number of urban banking consumers with internet access will be 250 million people, they say.

“Companies like ours will definitely benefit,” says Sampad Swain, founder of Instamojo in Bengaluru, who has spent the last five years helping some 300,000 micro-, small-, and medium-sized businesses accept online payments. Swain is now looking to solve other problems for his customers—such as getting them a credit score, so they get easier access to loans from banks, which have also partnered Instamojo, or in the near future, getting them good-quality shipping services from top-notch logistics firms in the country, for their relatively small numbers of orders.

PhonePe’s calculator-POS might solve one more infrastructural problem for the 50-60 million or so small businesses across India and help them go electronic and online for payments.

And, the device is so cheap that losing it won’t be high on the list of worries for the merchants. Even having one stolen won’t cause problems, Nigam says, because the merchant’s ID is hardwired into the unit. For everyone else, “It’s only a calculator.”

The POS solution is only really the tip of the spear with which Flipkart, a giant backed by a much bigger giant, Japan’s SoftBank Group Corp., is attacking the Indian fintech opportunity. “This is just the first of many solutions we will be releasing,” Nigam says. It’s only a matter of time before data from the POS device’s transactions helps PhonePe profile the small merchants on its platform and offer loans to them, for example.

Competitors are already on the same wavelength. “The future will see Mobikwik transforming into a fintech powerhouse, and by 2020, we aim to empower a billion Indians with one- tap access to digi-finance, payments, savings, lending, investments, insurance and so on,” says Upasana Taku, co-founder at New Delhi’s One Mobikwik Systems, widely seen as one of the largest mobile wallet providers in the country after Paytm.

Digital money is becoming more powerful and smart, and millions of Indians are joining the digital bandwagon to benefit from it. It saves time, and also delivers more value for money, Taku says.

As consumers shift to digital money, and with a growing history of using services from companies such as Mobikwik, there is a goldmine of data to be tapped. The data from users’ history of transactions, enables fintech companies and other businesses to gauge their creditworthiness. Mobikwik, for instance, has partnered banks and insurers to offer loans and insurance products, Taku says.

This recognition has seen some of the world’s biggest companies turn their attention to India’s fintech opportunity. Not only will Flipkart and PhonePe have to contend with Paytm, backed by China’s Alibaba Group, and Amazon Pay, which the Seattle-based online commerce giant is offering on its Indian site already and also Google.

Google recently launched Tez (meaning ‘speed’ in Hindi), its own smartphone-based mobile payments app in India. The app has seen brisk downloads on Google’s app store Play and it works with UPI from the get-go, Google’s senior executives have pointed out.

Flipkart and PhonePe will rely on their deep understanding of the Indian market.

For instance, they are already planning to soon launch “hyper-local services,” says Pradeep Dodle, PhonePe’s head of business development, and one of Flyte’s original team members, many of whom are back under the current venture’s roof. Dodle also has to his credit the launch of Ola Prime, at the cab-hailing venture ANI Technologies, where he spent some 7-8 months managing some of the categories, he says, in between Flyte and PhonePe.

A typical example of the hyper-local service could be Ola looking to expand in a new town, say, and a consumer tapping her phone at a POS device in a shop, getting pleasantly surprised with a discount if she took an Ola ride back home with her shopping. Any number of variations are possible on the theme, and PhonePe will try many of them.

“Some of our competitors are trying to do everything on their own… movies, flights, tickets,” Dodle says, without naming any company specifically, but one can guess he’s perhaps referring to Paytm. PhonePe’s approach will be to open the app to a multitude of partners, “so you could sit at home and order groceries on it, for example,” he says.

The groceries could even come from your friendly neighbourhood kirana store. How PhonePe will plan and implement the search and discovery needed for this is something they’re holding close to their chest for now, but it will happen sooner rather than later.

It would have been difficult to surmise all of this from Flipkart co-founder Binny Bansal’s tweet shortly after the company scored $1.4 billion from Tencent, eBay and Microsoft in April. “PhonePe is next,” he had tweeted at the time. Well, PhonePe has announced its intentions now, and it’s game on.

First Published: Dec 05, 2017, 05:50

Subscribe Now