Marico's Unique Paras Strategy

Marico learns to juggle old and new businesses after acquiring Paras's personal care brands

When Marico decided to try on a new hat, it also committed itself to a different, more vibrant, personality. Juggling personas was never going to be easy but here’s proof that the company known for its steadiness, manifested in brands like Saffola and Parachute, is ready to step away from its long-standing staid avatar.

Consider this advertisement. Its narrative goes like this: Two young television jockeys are shown complaining about the quality of participants at a talent hunt. “Pata nahi kahaan se aa jaate hain. Unko maloom nahi, yeh talent hunt hai, unki gaon ki nautanki nahi [Don’t know where they land up from. They don’t know, this is a talent hunt, not a village nautanki],” says one dismissively. On cue, the maligned participant pulls out a can of Zatak deodorant the cap flies across the room and lodges itself in the jockey’s mouth rendering him unable to speak while the participant sprays himself. ‘Who’s the cool one now?’ the advertisement seems to ask. The jockeys are humbled and the underdog prevails.

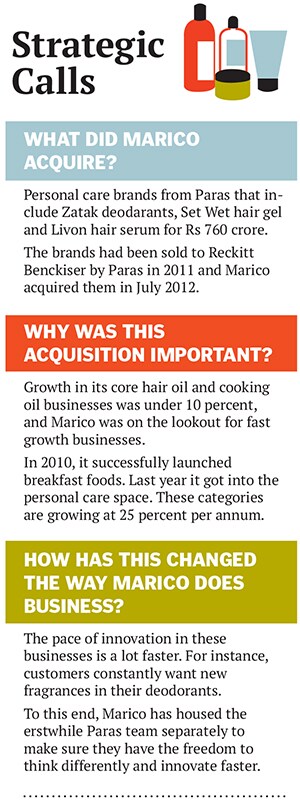

The tone of this campaign is in-your-face, suggesting a departure from Marico’s traditional approach—remember the Parachute hair oil commercials? Significantly, this is a sign of the leap of faith Marico is taking as it digests the acquisition of Paras Pharmaceuticals’ personal care brands. It completed the Rs 760-crore purchase from Reckitt Benckiser (the UK consumer goods giant had earlier acquired those brands from Paras) last July and has been on a learning curve since then.

Winds of change

Prompted by the sluggishness in its core businesses of hair oil and cooking oil, Marico had, a few years ago, taken a strategic call to tap new categories. “We wanted to enter categories that create tailwinds,” says Saugata Gupta, CEO, Marico. He means businesses that are poised to grow faster given that they cater to the 250 million Indians under the age of 35.

Subsequently, in 2010, it launched breakfast cereals under the Saffola brand and has since garnered an impressed 14 percent share in the category behind market leader Quaker Oats.

Personal care presented an opportunity with significantly better growth rates. In late 2011, when Reckitt Benckiser—which had bought the Set Wet hair gel, Zatak deodorant and Livon hair serum brands from Paras—put them up for sale, Marico was quick to enter the competitive bidding process. “Simply put, if we could not acquire this business, we would have had to build it,” says Sameer Sathpathy, chief marketing officer.

Marico has already notched impressive gains in these categories. Its success mantra: Learning to do business in a new way for an audience that is more aspirational, even fickle.

Why personal care?

In 1962, when Harsh Mariwala joined the family business at Bombay Oil Industries, he had no clue that there would come a time when he would have to look outside its staple hair oil business for growth. Still, in the early 2000s, the company found itself in that position and ventured into the cooking oil business with Saffola, a brand built on the promise of lower cholesterol. Sales soared as health-consciousness rose in urban India. Between 2000 and 2010, the company’s market capitalisation increased more than 10-fold, from Rs 800 crore to Rs 13,000 crore.

But by the end of the decade, Marico found itself in the search for more options in areas that could be considered ‘businesses of the future’—that is, those that take advantage of India’s young demographic. Breakfast cereals, as mentioned earlier, presented one such opportunity, while personal care emerged as another. “We needed a portfolio that was in line with future trends and left a lot of headroom for growth,” said Mariwala.

Personal care brands had been benefitting from the surge in personal grooming in India. They boasted growth rates of 20-25 percent, far higher than the seven percent seen in Marico’s core categories. This was identified as an attractive category.

The choice was build versus buy. Setting up the business from scratch would have taken three to five years and come at significant cost. A national advertising campaign would set the company back by Rs 25-30 crore. Add to that, the cost of strengthening distribution. Contrast this to an easier, stable entry that the Paras brands would provide. It was a no-brainer.

But the acquisition had its own set of challenges. Reckitt Benckiser had stopped investing in the brands, given its disinterest in retaining them. Consequently, they had lost market share as well as recall. While Marico’s primary task was to fuel growth, the other big job was integrating a smaller but more strategic business into the company. Integration issues have been known to adversely affect brands. It knew it would have to tread carefully.

Keeping it Separate

To begin with, Marico could not allow Paras’ brands to be subsumed by the larger company. A well-established consumer goods player, it had corporate systems and processes in place. Further, these were tailored to the hair and cooking oil categories, “boringly stable businesses” as Gupta describes them. The youth-oriented consumer businesses did not have room for stodgy practices.  The solution: House the new team separately. Much like Axe employees who are seated in an office outside the Unilever headquarters in London, Marico chose to keep the new group in New Delhi away from its head office in Santa Cruz, Mumbai. This physical distance allows the team to function with the same agility as it did when it was under Paras.

The solution: House the new team separately. Much like Axe employees who are seated in an office outside the Unilever headquarters in London, Marico chose to keep the new group in New Delhi away from its head office in Santa Cruz, Mumbai. This physical distance allows the team to function with the same agility as it did when it was under Paras.

The personal care space is characterised by what analysts call non-stop innovation. For instance, it took Marico just six months to change the packaging for Zatak deodorants.

The advertising, too, needed a fresh approach. The older campaigns appealed to the youth in a somewhat sedate manner. The newer ones have a breezier feel, more relatable for an under-35 audience. “This is a business characterised by high advertising spends and this is the only way one can stay ahead of the game,” says Abhneesh Roy, an analyst with Edelweiss.

No easy road

This is largely because this category is beset with competitive intensity. For example, if you had stepped into Big Bazaar at Mumbai’s Phoenix Mills recently, you would have seen a counter stacked with deodorants with discount signs on them. On an average, they were being sold at 25-30 percent less than the sticker price. A fair number of those brands had been imported. Company representatives vied for customer attention as they offered new fragrances for testing.

As such, the personal care category demands constant advertising support across print, radio and television as well as social media marketing. Given the high margins the brands promised to deliver, Marico has decided to spare no expenses and to good effect. The company declined to specify how much it spends on advertising for the three brands. Under Reckitt Benckiser, Zatak and Set Wet had suffered due to a loss in advertising support. Both these brands now have a combined 5 percent market share, a throwback to their status in the Paras days. In the three quarters that Marico has worked with the brands, Zatak, Set Wet and Livon have grown by 26, 25 and 21 percent, respectively.

The growth hasn’t been painless. Distribution, for instance, has proved to be a challenge. With the old business, the company had built its strengths in servicing kiraana stores and modern trade. It now has to deal with cosmetics and chemist outlets as well.

Further, with consumers demanding regular replenishment of specific variants of a brand, the products have to be sold in units as opposed to being sold in boxes like Parachute and Saffola are. This adds to the complexity of managing the supply chain.

Then there is the demanding consumer base that not only wants deodorants and hair gels in different pack sizes, but also needs fragrances to be frequently refreshed. “One of the main challenges is to understand what fragrances are working in the market and then producing them quickly,” says Gupta.

Most importantly, housing a Rs 150-crore business, albeit a fast-growing one, is a costly affair.

Gupta is clear that it will take the company two more years to establish a winning position in the business. For now, he says, they are focussed on ensuring their brands’ visibility in the market.

Investors, meanwhile, have adopted a wait-and-watch attitude.

At Rs 209 a share as of July 12, Marico’s stock has barely moved in the last six months. This, however, can be attributed to growth and margin pressures in its core oils business. Market watchers say this stagnation does not reflect the long-term potential of the company. After all, the stock has gone up nearly 10 times in the last nine years. Further, they say the company’s initial approach in the personal care business shows Marico is on the right path towards building a long-term sustainable presence in this category.

First Published: Aug 07, 2013, 06:28

Subscribe Now