About 6 hours from Mumbai, in the village of Yelapur in the Sangli district of Maharashtra, Sangeeta Kamde starts her day at dawn and works for close to 9 hours a day for a monthly salary of ₹3,000, to support her physically disabled husband and two children. She is an Accredited Social Health Activist (Asha), a key component of the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM), which is one of the two sub-missions of the National Health Mission (NHM).

“I have not received my salary for two months now. Even if I borrow money from someone, how do I repay them?" she says, adding that on days when she does not get any transport, she walks up to 20 km for her work. Kamde often has no choice but to seek financial help from her mother, and takes up tailoring work for additional income. “Mahine ke ₹3,000 mein kya hoga humara [How will ₹3,000 a month suffice]?" she asks.

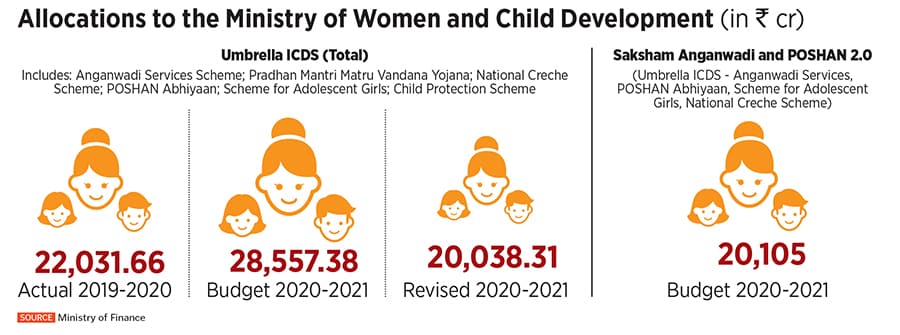

It has been about four years since the last pay hike. This, despite Sitharaman announcing an increase in allocations in 2021-22 towards ‘health and wellness’ by 137 percent to ₹2.23 lakh crore from the previous year’s budget estimate (BE) of ₹94,452 crore. However, the 2020-2021 budget included various sectors, including the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Poshan Abhiyaan, Department of Drinking Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Ayurveda, Yoga and Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (Ayush) and others.

The budget for the MoHFW alone dropped by about 10 percent, from revised estimates (RE) 2020-21 of ₹78,866 crore to BE 2021-22 of ₹71,269 crore. “We need to increase our investment in the public health system. India spends only about 1.2 percent of its total GDP on health care—one of the lowest in the world," says Dr Ambarish Dutta, public health expert and additional professor at the Public Health Foundation of India. The US, the UK and China spend 8.5 percent, 7.9 percent and 3.2 percent respectively.

Some of the significant schemes under MoHFW include Ayushman Bharat, Pradhan Mantri Swasthya Suraksha Yojana (PMSSY) and NHM. The allocation for Ayushman Bharat was more than doubled, from ₹3,100 crore in RE 2020-21 to ₹6,400 crore in BE 2021-22. The flagship scheme has two parts: Setting up health and wellness centres, and Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (PMJAY), which provides health insurance of up to ₹5 lakh per family.

Despite the focus on Ayushman Bharat in the last Budget, the scheme has been criticised. According to a September 2021 report by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII) and Boston Consulting Group (BCG), only 25 percent of beneficiaries eligible under PMJAY are enrolled under the scheme so far. “One major change that needs to be brought about," points out Dr Dileep Mavalankar, director, Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar, “is adding out-patient care, which is missing right now."

The question critics are asking is: How many people actually got treated for Covid-19 under PMJAY, and if they got treated in private hospitals, can they be reimbursed? According to a report published by Public Health Foundation of India and Duke Global Health Institute, “Despite its best intentions, the Covid-19 coverage by PMJAY remains extremely low at 1.77 million tests and 0.6 million hospitalisation, accounting for 0.49 percent and 14.25 percent respectively of the total tests and hospitalisation during the period from April, 2020 to June, 2021."

The private sector plays a significant role in the Ayushman Bharat scheme, as PMJAY provides health insurance for secondary and tertiary care hospitalisation across public and private empanelled hospitals.

![]()

“The reality is that the private sector has shown that they are not being able to deal with the kind of crisis we are going through—overcharging, rejecting critical patients, inducing unnecessary care are rampant. During the first wave, the private sector was shut. While PMJAY is being promoted extensively, I believe the focus should shift to strengthening primary care through NHM, and health and wellness centres," says Dr Indranil Mukhopadhyay, health economist and associate professor at OP Jindal University.

NHM saw barely a 4 percent increase to ₹36,576 crore in BE 2021-22. The scheme focusses on health system strengthening, reproductive, maternal, neonatal and child health, adolescent health and communicable and non-communicable diseases in rural and urban areas.

Kamde says there are four Ashas in the district, handling 12 villages. This means there is one Asha for 4,000 people. “During the pandemic, Ashas were the only frontline workers available on ground. Similarly, on an average there is only one nurse for five villages. That is not enough. There has to be more investment in terms of human resources," says Mavalankar. “What we need are strong primary care and secondary care."

*****

In our village, there are two children who are extremely underweight," says Bharati Chauhan, the only anganwadi worker in Waghjipur village in Sanand, about 150 km from Ahmedabad in Gujarat. “Due to the pandemic, children aren’t coming to the anganwadi anymore, but we make sukhdi (an Indian sweet made from wheat flour and jaggery in ghee) for them every Thursday, and send it to their homes."

But that alone is scarcely a good enough replacement for mid-day meals, which have been stopped due to the pandemic. Before Covid-19, Chauhan and her helper would provide children with two meals a day, one at 11 am and another at 2 pm. “We would cook hot meals in the anganwadi and teach them how to eat—not to remove vegetables, not to waste food," she says.

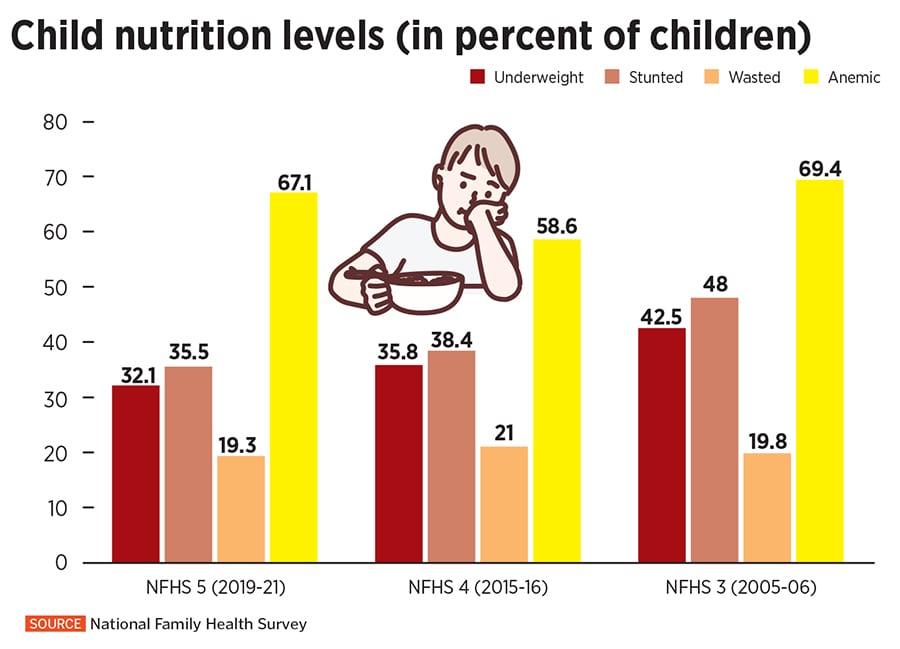

As of October 14, 2021, the Ministry of Women and Child Development estimates that there are 17.76 lakh severely acute malnourished (SAM) children and 15.46 lakh moderately acute malnourished (MAM) children in India.

In order to reduce malnutrition, the Poshan Abhiyaan scheme was launched in 2018. Also, the government provided additional nutrition through the Supplementary Nutrition Programme (SNP) under Anganwadi Services (AWS) and Scheme for Adolescent Girls (SAG) under the umbrella Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme to children (6 months to 6 years), pregnant women, lactating mothers and out-of-school adolescent girls (11-14 years). In Budget 2021-2022, Mission Poshan 2.0 (Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0) was announced as an integrated nutrition support programme.

Experts were hoping for an increase in allocations for nutrition. However, says Mukhopadhyay, “While they’ve clubbed all the schemes under Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0, the overall allocation has reduced." The total BE for ICDS was ₹28,557 crore in 2020-21, and the RE dropped to ₹20,038 crore. In Budget 2021-22, the BE under Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 is ₹20,105 crore, almost a 29 percent drop. And although there is an existing SAG, Mukhopadhyay feels, “We need to focus on nutrition for girls in the adolescent age group. That’s where a lot more resources need to go in."

![]()

Pallavi Patel, director of Chetna, an Ahmedabad-based NGO, says schemes like Poshan 1 and 2 are well documented, with all aspects being taken care of. But there are gaps in implementation. “The execution should be done strategically, with a proper provision of finance and human resources, with an involvement of NGOs, because they are working at the ground level," she says. “Spending money on television advertisements might have no value the Budget should be decentralised at a district and block level, for them to decide what kind of awareness should be generated."

As part of ICDS, Take Home Ration (THR) is provided for children aged 6 months to 3 years, and pregnant and lactating women. “However," says Patel, “due to the severe food insecurity in most rural households in India, THR gets distributed among other family members, and rarely has any effect on women and children."

The mid-day meal scheme, run by the Ministry of Education, provides hot-cooked meals to all children studying in classes 1 to 8 in government and government-aided schools. As per RE 2020-21, ₹12,900 was allocated to the scheme, which dropped to ₹11,500 crore during BE 2021-22, a 10.8 percent drop. “The impact of closing down mid-day meals and ICDS during the pandemic is likely to be disastrous, pushing children into severe under-nutrition," says Mukhopadhyay.

On September 29, 2021, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs approved the new Pradhan Mantri Poshan Shakti Nirman scheme for government and government-aided schools for 2021-22 to 2025-26, with a financial outlay of ₹1.31 trillion. The existing mid-day meal scheme will be included in this programme. “There are already enough schemes and programmes. It’s not that we need more schemes, but we have to strengthen the existing ones and provide better quality nutrition and prioritise protein-rich foods like eggs," says Mukhopadhyay.

*****

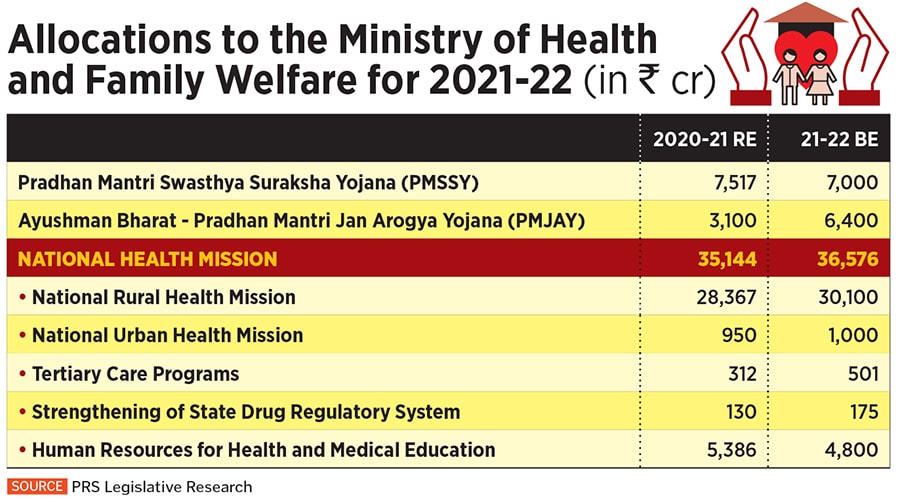

The number of people seeking work under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) increased by 43 percent to 133 million in FY 2021-22. However, the government reduced the allocation for the scheme by 35 percent in 2021-22.

All of the ₹73,000 crore allocated to MGNREGA in FY 2021-22 has already been utilised, and 21 states currently have a negative net balance of funds. The Government of India allocated additional funding of ₹25,000 crore to MGNREGA and the total allocation now stands at ₹98,000 crore.

![]()

The Centre allocated ₹61,500 crore for the programme in 2020-21, before it announced a national lockdown, which witnessed a mass exodus of workers from cities to their homes in rural India. It increased the allocation by 81 percent to ₹1,11,500 crore in 2020-21, but subsequently reduced it by 34 percent to ₹73,000 crore for 2021-22.

Activists say that with little money left, payment of wages will get delayed, as it has happened each year. This will discourage workers from MGNREGA work, leading to depressed rural consumption and causing continued stagnation of the economy. The additional ₹25,000 crore that has been allocated is not even close to the amount of additional funding required for MGNREGA to be implemented properly.

Implemented in 2006, MGNREGA aims to provide at least 100 days of unskilled wage employment to adult members of a rural household, and is meant to be a lifeline for the rural poor—nearly 147 million active workers—during times of economic distress and natural calamities. Yet, this programme has major setbacks due to various reasons like delayed payments and unavailability of work.

“There are many loopholes in the entire process," explains Richa Singh, a member of Sangtin Kisan Mazdoor Sangathan (SKMS), in the Sitapur district of Uttar Pradesh. “It’s very difficult to get work under MGNREGA. And even after getting work, another problem is getting payment on time. For instance, there’s a woman named Reena who has not received her payment for the last two years. We’ve been fighting to get her 90 days of wage payment of ₹18,000. This situation is really sad. The government doesn’t have any intention to resolve their problems. There is no regularity of giving them work when they need it."

According to a study by LibTech India and People’s Action for Employment Guarantee, as of December 4, 2021, more than ₹4,500 crore in wages is pending with the Centre, beyond the stipulated 7-day period. The number of transactions pending at the Centre are 2.88 crore, or 9.7 percent of the total number of wage transactions.

“Often, payments are rejected due to technical reasons. Too much digitisation makes it difficult for labourers to get their payment on time," says Singh. Last year, 64.36 lakh transactions, or more than 2 percent of the total number of transactions, were rejected. Of these, 50.42 lakh transactions still stand rejected, amounting to ₹280.42 crore in rejected wage payments.

The government actually cut allocations to two major programmes—MGNREGA and the National Food Security Act—which saved the government in 2020-21, says Nikhil Dey, founder member of Mazdoor Kisan Shakti Sangathan (MKSS) & National Campaign For Peoples Right to Information (NCPRI). Both these schemes saved millions of Indians from starvation after complete loss of their livelihoods. Although the government has repeatedly promised that there is no shortage of funds, the ground reality appears to be different.

“When there is no money in the pipeline, people stop coming to work. They get disappointed and frustrated with the scheme," says Dey. “There are people who live a hand-to-mouth existence. The government does not even pay the required compensation of .005 percent per day for delayed wage payments, and they hide the delay on the management information system [MIS]. So there are multiple ways in which the government is showing how it’s violating the law."

The issues that people are facing on the ground are a routine set of issues, says Rakshita Swamy who is associated with the People’s Action for Employment Guarantee (PAEG) and Social Accountability Forum for Action and Research (SAFAR). When people submit their demand for work applications, they are not provided dated receipts. Because under the law, if work is not provided to an applicant within 15 days of application, then the state government is bound to pay an unemployment allowance to them.

“Administration or field level functionaries don’t give these receipts. So that is one of the major challenges that workers are facing. The second, of course, is delayed wage payments, which is not so much on account of logistical issues like banks or Aadhaar, but because of inadequate funds. If you see the MIS, many states are in the red, and they have a negative balance, which means they have given work to MGNREGA workers but they’ve not been paid wages. These are some of the major challenges that need to be addressed immediately."

The number of people seeking work under MGNREGA increased by 43 percent to 133 million in FY 2021-22

The number of people seeking work under MGNREGA increased by 43 percent to 133 million in FY 2021-22